Europe’s Growth Engine Sputters

Europe’s Growth Engine Sputters

(Bloomberg) -- The command center at the Otto Junker GmbH metals plant stands in sharp contrast to the noisy and smelly factory floor, where until just a few weeks ago workers operated various machines individually. The new digs are quiet, there’s no oil stench, and there’s even room for a coffee maker. The downside? The control room boss may end up drinking that coffee alone, because running the machines requires just one person, down from about a half-dozen.

The 95-year-old company—in the town of Simmerath, just a few hundred meters from the Belgian border—is preparing for storm clouds gathering over German industry. Chief Executive Officer Bernward Reif says Otto Junker, which builds furnaces that can melt tons of metal in minutes, must adapt to a changing economy by improving the productivity of its 480 employees. That has spurred him to propose initiatives like building the control room and shifting more work to its facility in the Czech Republic, while investing in technologies such as 3-D printing and wireless apps.

“The environment is more volatile,” Reif says as he passes freshly cast metal pumps that are still too hot to touch. “It means we have to become more productive and flexible.”

Like Junker, companies ranging from tiny family-owned engineering specialists to global giants such as Volkswagen AG are doing what they’ve long done: transforming themselves to meet the demands of a shifting global order. But this time, the stakes seem higher as the world is riven by trade conflicts and as value moves from old-school engineering—Germany’s traditional strength—to digital technologies.

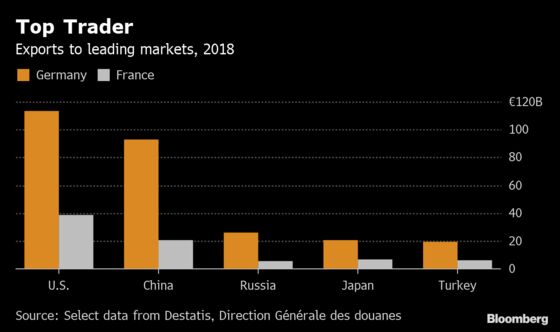

The country’s export-focused industrial base, the motor of its growth, today is becoming a disadvantage. Faced with the challenges posed by Donald Trump’s America First protectionism and China’s slowdown, the country is at greater risk than, say, neighboring France, because of Germany’s greater reliance on selling manufactured goods.

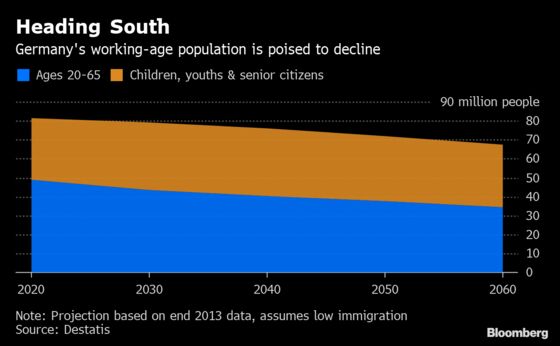

The longer term challenges may be even more vexing. Transport infrastructure is crumbling, data networks are patchy, the population will start shrinking in the coming decade, and the crucial auto industry risks getting sidelined by the emergence of self-driving electric cars.

“On top of the normal level of investment, they’ve got the additional demand of trying to find the right answer for these new technologies,” says Peter Wells, a professor at Cardiff Business School who studies global auto manufacturing. “German industry has been quite firmly in denial about the prospects for electric cars,” and now is trying to catch up.

The strains are undeniable. The European Central Bank on Thursday announced a new stimulus program and cut its 2019 forecast, predicting expansion of just 1.1 percent. German industrial output fell 3.3 percent in January from a year ago, a third straight decline. The country narrowly avoided a recession at the end of 2018 after automotive bottlenecks from emissions changes caused a contraction in the third quarter. And growth this year is forecast to be the weakest since 2013—spurring the government to propose a national industrial policy for the first time in Chancellor Angela Merkel’s 14 years in power.

Still, Germany has a strong track record of adaptation. It emerged from the ashes of World War II to become the industrial powerhouse of Europe, and the integration of the communist East after the fall of the Berlin Wall 30 years ago has been largely successful. Its labor force is among the world’s most efficient and skilled, and its education system includes 10 universities on the Times Higher Education rankings of the world’s top 100 universities.

“We have an amazing wealth of possibilities in Germany, which I’d venture to say doesn’t exist anywhere else,” says Joachim Schulz, CEO of Aesculap, a manufacturer of surgical tools such as scalpels, forceps, and bone saws.

Schulz says that’s evident in Tuttlingen, where the company is headquartered, about 25 kilometers (15 miles) north of the Swiss border. The town of 36,000 is home to some 400 medical tech companies, providing a deep pool of potential workers, especially if, like Aesculap, you’re the biggest player in town, with 3,600 employees there.

The pressure is especially intense in the automotive sector, where manufacturers and component makers alike are scrambling to adapt. Schaeffler AG is cutting 700 jobs in Germany in an overhaul of its parts business aimed at reducing reliance on the combustion engine. To boost its expertise in driver-assistance, transmission specialist ZF Friedrichshafen AG is in talks to buy Wabco Holdings Inc. for some $9 billion. And Continental AG is considering a sale of part of its powertrain business to increase investment in electronics.

The most radical changes are underway at Volkswagen, which is still recovering from the 2015 emissions cheating scandal that tarnished both the company’s image and the broader Made in Germany brand. The world’s largest automaker says it will spend $50 billion to develop scores of battery-powered cars by 2025 and retool factories to build them.

For instance, a factory in Dresden—a bright and airy space originally set up for the Phaeton, an ill-fated luxury sedan meant to showcase VW’s engineering prowess—has shifted to assembly of electric variants of the Golf hatchback. Last year, the facility hit a production record.

This winter, the government proposed its industrial strategy in response to fears that Germany will get squeezed out by the U.S. and China as the global economy shifts to new technologies. The program calls for defending German leadership in key sectors like metals and machinery, and investing in technologies such as artificial intelligence, which the report calls likely the most important development since the steam engine.

“We’ve spent too much time discussing the small questions facing this country and not enough time on the big questions,” Economy Minister Peter Altmaier said at the presentation of the program last month in Berlin. “It’s about whether the enormous affluence we’ve achieved over the last 70 years can be maintained and expanded.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net, Simon KennedyChad ThomasFergal O'Brien

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.