Fallen-Angel History Shows Colombia’s Fear of Junk Is Misguided

Fallen-Angel History Shows Colombia’s Fear of Junk Is Misguided

(Bloomberg) -- Colombia’s all-out effort to preserve its investment-grade credit rating has fueled bloody street protests, cost the finance minister his job and thrown the country into its worst political crisis in years.

The human misery is palpable. And for what?

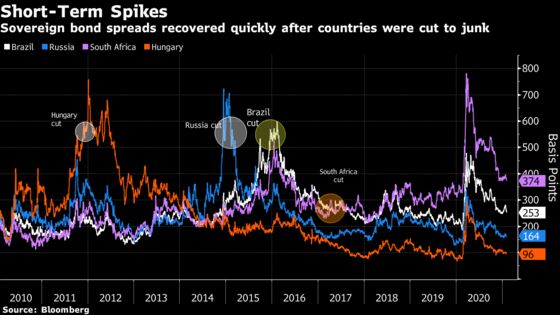

Recent history shows the financial hit was minimal for developing nations that lost investment-grade ratings on their debt, so-called fallen angels. Brazil, Hungary and Russia saw only short-lived spikes to their borrowing costs when they were downgraded to junk status over the past decade, with most of the damage erased within months. In other words, the financial savings bestowed by an investment-grade rating are small nowadays.

Which makes Colombia’s gung-ho push to appease credit-rating analysts with tax hikes and spending cuts -- even as violent protests erupt across the country -- seem misguided to some. Unlike the many countries that continue to borrow and spend to spur growth amid the pandemic, Colombia has now prioritized keeping bond vigilantes at bay and convincing ratings companies it’s one of Latin America’s rare investment-grade credits.

“What matters right now is stabilizing the economy and employment, strengthening institutions, before we think about maintaining investment grade,” said Juan David Ballen, director of research and strategy at Casa de Bolsa, a brokerage in Bogota.

President Ivan Duque withdrew the first tax bill amid the unrest. The unpopular finance minister who drafted it stepped down a day later. But that failed to quell protesters, who have been out every day the past week in demonstrations that have turned increasingly violent.

Vandals have torched police units and destroyed bus stations. More than 20 people have been killed, leading to international condemnation of heavy-handed policing. With roads blocked by protests, shipments have been stranded, causing growers to freeze coffee exports and leaving millions of chickens at risk of dying because food can’t get to them.

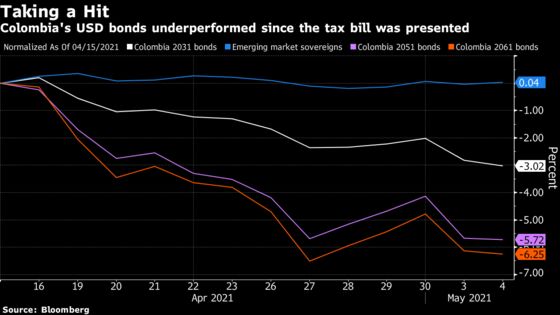

The peso has dropped to a six-month low and Colombia’s dollar bonds are the worst performers in emerging markets, swelling the average yield spread over Treasuries to about 2.4 percentage points. It’s difficult to discern how much of the pessimism is driven by investors concerned about the effects of a cut to junk at this point, as analysts and money managers have also warned of the potential for the social chaos to weigh on economic growth.

Newly appointed Finance Minister Jose Manuel Restrepo affirmed his commitment to avoiding a junk rating, one level below the current classification, in an interview Wednesday. He said a new tax plan in the works will rely on wealthy individuals and corporations to shore up government finances, instead of the middle class.

“For us, investment grade is closely linked to the country’s commitment to fiscal stability,” Restrepo said. “Colombia is aware that it must necessarily guarantee the stability of its public finances and its stability from a social perspective.”

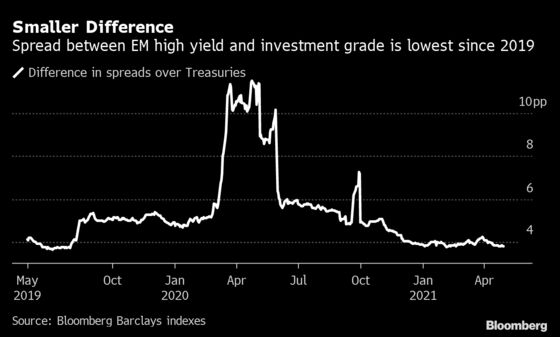

Yet if it is downgraded, Colombia may find joining the junk community isn’t all that bad. The extra borrowing costs for junk-rated, emerging-market issuers over investment-grade peers has dipped to the lowest in almost two years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That’s partly because investors flush with cash are desperate for returns amid the more than $13 trillion of negative-yielding debt globally and benchmark rates near zero in much of the developed world.

And while the currency and corporate bonds would likely get hit, most of the selling usually comes in the run-up to the downgrade, according to research by Citigroup Inc. that focused on Brazil, Hungary, Russia and South Africa. Bond yields tend to spike in the short term, but quickly fell back to pre-downgrade levels. Sovereign spreads for three of those countries are currently below the average for developing nations, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“After that first downgrade, there tends to be stabilization on the rates side, which provides a better entry point and opportunities,” said Alvaro Mollica, a macro strategist at Citibank based in New York.

The worst of the selling may already be behind Colombia as investors wait and see how the new tax proposal will shake out. In the meantime, some are willing to give the benefit of the doubt, considering the country is one of the few in a region of serial defaulters to consistently pay its debts, having not missed payments since the Great Depression.

“One of Colombia’s long-standing strengths from a credit profile has been consistent center-right, conservative economic regime relative to peers in the region,” said Jonathan Davis, a money manager for emerging market debt at PineBridge Investments LLC, which holds Colombian dollar and local bonds.

Davis is optimistic Colombia can pass a new tax bill and hold onto its credit grade for now. Still, considering recent events, “it’s not unwarranted for investors to take a heightened risk view of the likelihood of a downgrade.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.