(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s been a week of milestones for Exxon Mobil Corp., and not in a good way. The oil major froze its dividend for the first time in 13 years and then, on Friday morning, announced its first quarterly loss in decades. Covid-19 plays a big part, obviously, but Exxon’s strategy is the big problem, particularly on its home turf.

As at the company’s March analyst day, CEO Darren Woods began with a familiar declaration of long-term growth trends for oil and gas. Even back then, this “straight line” view of global energy’s future looked questionable. Eight long weeks on, it looks divorced from reality; the very first analyst question gently raised that possibility, citing jet fuel in particular (which is critical). Exxon’s high-spending strategy implicitly demands a recovery in oil and gas prices, which makes it more like an exploration and production company than a major. While the company has slashed this year’s capex budget to $23 billion, that remains above the pre-Covid guidance for rival Chevron Corp.

One of Woods’s more striking statements was that Exxon will take the number of rigs it has operating in the Permian basin down by 75% to 15 this year. That new level is roughly where Chevron, the second biggest operator by rigs, was before this crisis struck. So Exxon’s prior push in shale is what you might call vigorous. And therein lies a big problem: That business also happens to be a huge drag on Exxon’s returns.

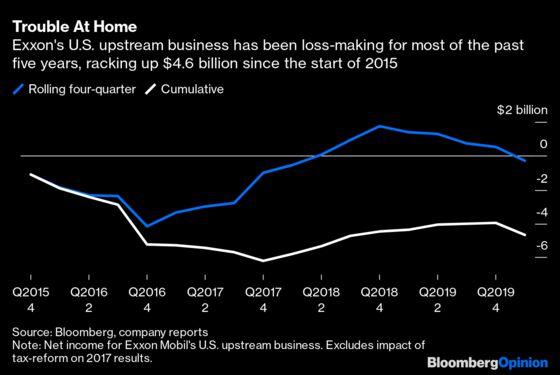

Of 21 quarters since the start of 2015, Exxon’s U.S. upstream business has been profitable in just eight of them. Yet it has accounted for more than a quarter of capex and fully two-thirds of asset impairments. In early 2019, Exxon was projecting $5 billion of free cash flow from its Permian business in 2023. It was an astounding number then. A year on, it looks fantastical.

This all feeds into the bigger problem: Exxon’s much diminished reputation for capital discipline.

Having racked up the sixth quarter in a row of negative free cash flow, Exxon was bound to get some direct questions about the sustainability of its dividend. As it is, the changing dynamics of the mature oil industry raise doubts about the wisdom of having a progressive dividend in the first place (see this), emphasized by Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s shock cut this week. Woods dismissed the comparison, but there is one uncomfortable similarity between the two companies.

Evercore ISI analyst Doug Terreson notes that, even before Covid-19 showed up, Shell had spent $125 billion and increased net debt by more than $50 billion between 2015 and 2019. The result: Return on capital employed dropped by half, even though oil prices increased by 20% across the period. Calculating the same figures for Exxon from the Bloomberg Terminal, Exxon spent $102 billion and increased net debt by $25 billion. Return on capital dropped 40%.

A progressive dividend demands investment in the underlying business. But the pace at which Exxon is remaking itself, exemplified by the plunge into shale, has left it relying more and more on the balance sheet to take the strain. Net debt to capital jumped 5 percentage points over the past year, with almost half of that in the last quarter alone. And the current quarter’s impact on earnings will be worse.

Woods noted Friday that one reason to defend the dividend is the fact that 70% of the shareholder base is made up of retail and long-term investors who rely on those checks. Like the company’s dogged expectation of long-term growth for oil and gas, and the capex spree that supports, those shareholders may be clinging to past glories.

This excludes the one-off effect of U.S. tax reform in 2017.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.