Exxon at a 10-Year Low is Challenge for Oil’s Biggest Major

Exxon is ramping up capital spending to more than $30 billion a year, without a hard ceiling.

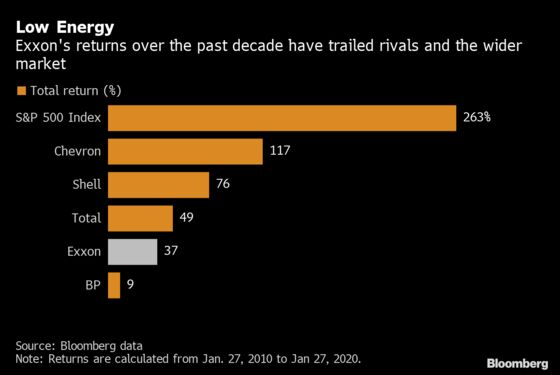

(Bloomberg) -- It’s almost as if the last decade never happened for Exxon Mobil Corp. shares.

Once the gold-standard of Big Oil, the stock closed Monday at its lowest since October 2010, amid a slump in oil prices due to concerns about weak demand coupled with a glut. The S&P 500 also posted its worst one-day decline since October.

But for Exxon, which dropped out of the index’s top 10 largest companies by market value for the first time last year, the malaise runs deeper than the state of the crude market.

Chief Executive Officer Darren Woods is running a counter-cyclical strategy by plowing money in new oil and gas assets, at a time when many investors are urging energy companies to improve returns for shareholders. Some shareholders are even demanding a plan to move away from fossil fuels altogether.

Exxon is betting on a “windfall of cash” to arrive from its investments sometime in the mid to late 2020s, said Noah Barrett, a Denver-based energy analyst at Janus Henderson, which manages $356 billion. “Right now there’s higher value placed on generating cash flow today.”

Exxon is ramping up capital spending to more than $30 billion a year, without a hard ceiling, as it develops offshore oil in Guyana, liquefied natural gas in Mozambique, chemical facilities in China and the U.S. Gulf Coast, as well as a series of refinery upgrades. Woods is convinced the world will need oil and gas for the foreseeable future and sees an opportunity for expansion while competitors shy away from such long-term investments.

Most of these investments “will not meaningfully begin contributing to earnings/cash flow until the 2023-2025 time frame,” Scotiabank analysts led by Paul Cheng said in a Jan. 23 note, downgrading the stock to the equivalent of a sell rating from hold. “We think it may be another one to two years before the market gives these efforts much credit.”

In the short term, one consequence of those investments is that Exxon can’t fund dividend payouts with cash generated from operations, and must instead rely on asset sales and borrowing, according to Jennifer Rowland, an analyst at Edward Jones & Co. Exxon is the “clear outlier” among Big Oil companies on that front, she said. Exxon declined to comment.

Exxon’s current challenges stem in large part from flag-planting deals made when commodity prices peaked during the past decade. It spent $35 billion on U.S. shale gas producer XTO Energy Inc. in 2010 when shale oil promised outsize returns. It has invested $16 billion in Canadian oil sands since 2009, only to remove much of those reserves from its books. Former CEO Rex Tillerson’s 2013 exploration pact signed with Russia was caught behind a wall of sanctions and later abandoned.

To contact the reporter on this story: Kevin Crowley in Houston at kcrowley1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Casey at scasey4@bloomberg.net, Christine Buurma, Reg Gale

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.