Your Bowl of Pasta Is Getting More Expensive as Drought Zaps Wheat Fields

Get ready to pay more for your pasta as drought drives up price of vital durum wheat.

(Bloomberg) -- So much for cheap noodles.

Pasta is poised to become the latest staple consumers are forced to pay more for after drought scorched North American production of durum wheat, the high-protein grain that’s milled into semolina flour for spaghetti. Output of durum in Canada, a top exporter, shrunk by nearly half this year and the U.S. harvest is the smallest in 60 years.

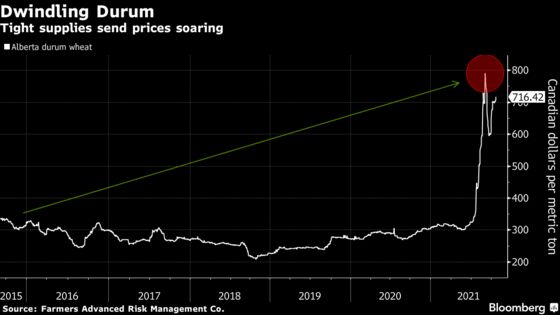

Durum prices in the western Canadian province of Alberta have risen more than 60% since August and are currently trading near the highest since at least 2015, according to data from Farmers Advanced Risk Management Co. in Winnipeg.

“Prices are quite a bit elevated from what they were at the end of June and the fears that everybody had at that point have come to realization,” said Jim Meyer, president of St. Louis-based Italgrani USA, North America’s largest semolina and durum flour miller. “It’s going to be reflected in higher costs at the grocery store.”

In North Dakota, the U.S. Midwest state that grows about 80% of the nation’s crop, prices at grain elevators have nearly doubled since June, Meyer said. While higher prices are unlikely to slow buying from U.S. manufacturers, he said it will add to costs and further strain businesses challenged with supply-chain disruptions and worker shortages.

Durum’s squeeze comes as harvest disruptions, supply-chain snarls and strong demand have sent a United Nations index of food costs up by nearly a third in the past year. Food processors started to see ingredient prices rise in the summer and many are now passing on those costs to consumers, said Sylvain Charlebois, director of Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

“Something is giving and they don’t have much of a choice to increase prices,” Charlebois said Friday in a phone interview. “Everything is catching up to us right now. It’s only going to get worse.”

Italian Pasta

In Italy, big pasta producers are scrambling to stock durum wheat as production costs rise. The current grain price increase is affecting both hard and soft wheat, with an impact on bakery products, bread and other food given the parallel rise of other commodities including corn and barley, Italian farmers association Copagri said in an Oct. 20 statement.

Dario Monni, owner of pasta shop and restaurant Tortello in Chicago, said the semolina flour he ships in from his native Italy has risen 10%-12% in price since last year.

He’s hopeful he can avoid boosting menu prices as the cost of everything from food production to shipping rises.

“I consider it the cost of business and I’m hopeful it’s not going to be forever,” he said. “But of course if it is, then I’m going to have to increase some prices for sure.”

Spring wheat, used to make pizza dough and bagels, hit $10 a bushel for the first time since 2012 on Friday, thanks to drought in the U.S. and Canada.

Retail prices of macaroni in Canada are up 7% since May, while the U.S. Department of Agriculture sees wholesale wheat flour costs rising 15%-18% this year.

Drought

Swaths of the Canadian Prairies are under severe-to-extreme drought and exports of durum are expected to fall 46% in 2021 due to the short supply, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada said in an October report.

U.S. production of the grain plummeted 46% this year from 2020 levels as extreme drought baked North Dakota crops, with annual output at its lowest since 1961. The domestic market makes up two-thirds of demand for U.S. durum.

“Certainly the crop is the smallest in the last 60 years, if not longer,” Jim Peterson, policy and marketing director for the North Dakota Wheat Commission, said in an email.

The crunch comes just as pasta demand continues to climb after the pandemic spurred people to stock their pantries, said Dean Dias, head of Winnipeg-based Cereals Canada. Farmers may try to seed more durum next year if prices and demand remain high, he said.

“Even at a higher price they’re still going to be a cheap carbohydrate and people are going to buy it,” said Neil Townsend, chief market analyst at FarmLink in Winnipeg. “I don’t think we’re going to see a real dip in demand in North America.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.