European Police Hacked Secret Phone Network, Used AI for Major Bust

European Police Hacked Secret Phone Network, Used AI for Major Bust

(Bloomberg) -- French law enforcement had been watching a secret phone service called EncroChat for years — tipped off by clues that criminal groups were using the encrypted devices to evade police surveillance.

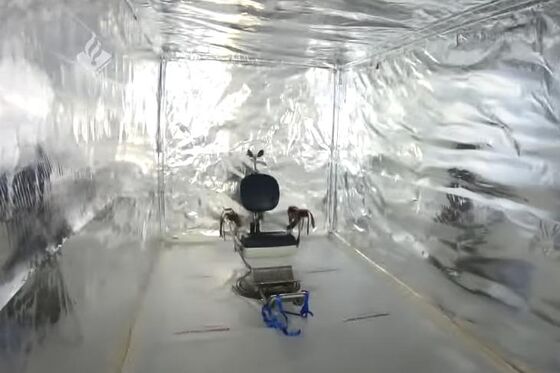

In 2018, authorities caught a break that would help them and their counterparts across Europe infiltrate the network and gain access to a trove of messages. They laid out alleged criminal schemes worthy of a “Breaking Bad” episode, including a crystal meth lab, planned executions, arms deals, kidnappings and a makeshift torture chamber in a shipping container. So far, police have made more than 840 arrests and confiscated 8,000 kilos of cocaine, weapons and tens of millions of dollars in cash.

In pulling off one of the most-far reaching law enforcement hacking operations ever, France's national police agency, the Gendarmerie Nationale, managed to infiltrate the encrypted communications of thousands of alleged criminals in one fell swoop. Interviews with top law enforcement officials and cybersecurity experts, and a review of confidential police files, provide new details on how it happened.

Use of encryption has exploded in recent years. Governments in Europe, the U.S. and elsewhere have engaged in a public battle with smartphone makers such as Apple Inc. and app developers such as Signal and Facebook Inc.’s WhatsApp for their refusal to make criminal suspects’ encrypted communications available to authorities.

But the EncroChat case turned that power struggle on its head. In this instance, French police infiltrated an entire encrypted network and accessed millions of messages that were intended to be secret. Such an action was warranted, police say, because EncroChat -- unlike the better known encrypted communication networks -- appeared to be used almost exclusively by criminals.

European law enforcement agencies are investing in research and technical solutions that aim to circumvent such communications, according to Matthijs Koot, a Netherlands-based security researcher. The Encrochat case indicates that those efforts are beginning to bear fruit. "Security is hard to get right, even more so if you need to protect against government actors,’’ Koot said. ``Those providing encryption services specifically to criminals will have a difficult time keeping themselves and their users safe from law enforcement."

The Gendarmerie Nationale had been stymied in efforts to investigate criminal activity on EncroChat because of the network's use of a specific type of “off the record” encryption which hid even basic information about its users and their communications. EncroChat didn’t help. Police couldn’t figure out who ran the company or where it was based. But in 2018, investigators got a tip from a foreign law enforcement agency that some of EncroChat’s servers were located in France.

The Gendarmerie Nationale’s cybercrime division, known as the C3N, carried out research on EncroChat’s phones and infrastructure. Then between March and early April of this year, C3N gained access to the servers, setting up a “technical device” to gather millions of texts messages sent between EncroChat phones, said Carole Etienne, a prosecutor who worked on the case. The C3N’s efforts were backed up by a team of computer science researchers, who specialize in extracting data from devices whose data has been scrambled by encryption, according to French police.

EncroChat, which is not longer operating, didn’t return messages sent to email accounts associated with the company.

EncroChat offered customized Android phones with security features that its marketing materials said “guaranteed anonymity,” using strong encryption to create the electronic equivalent of a “conversation happening in an empty room.” More than 50,000 users each paid about $3,500 annually for a subscription.

The anonymous people who ran the EncroChat phone network claimed, in an alert to its users, that law enforcement agencies hacked their server and, through that access, were able to send out some kind of malware onto their users’ handsets, perhaps under the guise of a legitimate software update.

Cybersecurity experts said the police don’t appear to have cracked the encryption that made EncroChat communications unreadable; rather, they probably found a way to bypass it.

Éric Freyssinet, head of cybercrime strategy for the Gendarmerie Nationale, who helped coordinate the team of about 60 investigators from across France, provided some clues on how they did it. “We have legislation that allows us to install software on a targeted device, either by having access to the device or over the network,” he said.

The police found a way to “piggyback on the servers of the EncroChat people,” Freyssinet said, adding that using updates to compromise the devices would have been “a possible way to do it.” He suggested the police had also found some data about EncroChat users that had been stored insecurely on the company’s servers, “either by mistake or weakness.”

Frank Groenewegen, chief security expert at Dutch cybersecurity company Fox IT, said that when police use malware to hack phones or computers, they will usually target only specific suspects and must prove to a judge that they are monitoring someone involved in serious crimes. If French authorities sent out malware in bulk to tens of thousands of phones in the EncroChat case, Groenewegen said, “That’s a big deal, because you don’t know the end user. Maybe it’s a lawyer, maybe it’s a journalist.”

Freyssinet said they hadn't yet encountered “any user that was not involved in illegal activities.’’

Whatever method was used to tap into the EncroChat network, it was extraordinarily successful. According to the Gendarmerie Nationale, investigators had access to more than 100 million messages and were able to review, in real time, communications over a period of several weeks.

Europol, the European police coordination agency, set up a joint team to process, analyze and share information. It also established a system that used artificial intelligence to scan the texts for particular words or phrases that might indicate that criminal actions, including murders, were being planned, said Wil Van Gemert, Europol’s deputy director of operations.

The messages exposed thousands of suspected criminal plots. But the police still had to do a substantial amount of investigating to tie the messages to particular people, according to police case files seen by Bloomberg. The text messages obtained by police weren't associated with particular phone numbers; instead, they had usernames, making it harder to find out the true identity of the people involved in the chats.

But some of the alleged criminals were sloppy. In between negotiating the purchase of secret drug factories and organizing shipments of cocaine, ecstasy, ketamine and cannabis, they used EncroChat to chat about everyday activities — and shared personal details about themselves, their children and their home addresses, the files show. These details helped police close in on particular suspects and carry out raids that netted cash, drugs and the EncroChat devices they had been monitoring.

The Gendarmerie Nationale hopes to identify the people who created, sold and maintained the EncroChat phones, alleging that they didn’t have the necessary authorization under French law to sell encrypted devices. Records associated with one of the EncroChat servers targeted by French police, seen by Bloomberg, show that the company at one point used an address in Panama, which was previously associated with a law firm that provides services to companies seeking incorporation, Arias B. & Associates.

M.A. Perez, a spokesperson for the firm, confirmed it had incorporated EncroChat in Panama in 2014, under the name Esocrypt Panama S.A., but said it had terminated the relationship in 2017 after it could no longer locate the company’s representative. The Panamanian firm hasn’t been contacted by law enforcement about Encrochat, Perez said.

Freyssinet said he believes as many as a few dozen people could be involved in EncroChat, in Europe and elsewhere. “The main suspects for us have not been arrested – the people behind EncroChat,” he said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.