Europe Can’t Stop Pandemic From Rocking Its Foundations

Europe Struggles to Stop Virus Infecting Its Foundations

(Bloomberg) -- An Estonian ferry sailing from Germany to the Latvian capital Riga will disembark more than 600 citizens from the Baltic states on Thursday night after they were unable to return home because Poland sealed its borders and effectively cut them off.

The 48-hour emergency return trek to repatriate people, though, portends an even greater problem for Europe as governments go it alone in trying to combat the spread of coronavirus: How to keep trade flowing in a market that was supposed to be seamless.

With much of Europe in lockdown not seen since World War II, responses to the spread of the Covid-19 outbreak are testing the most binding principle of the continent’s postwar integration project—the freedom of movement enshrined in the 27-nation European Union’s treaty.

Another ship will leave in the coming days shuttling food and medical supplies as well as passengers. Estonian Prime Minister Juri Ratas called the initiative “one very specific measure to allow us to ensure as free economic relations as possible in this difficult emergency situation.”

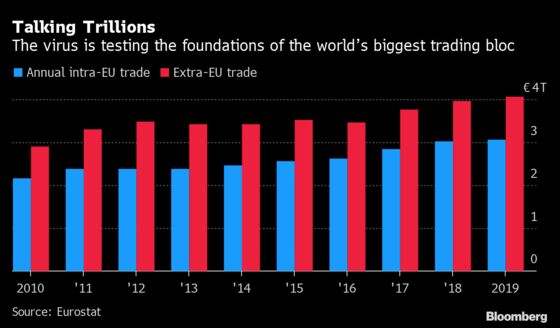

Unilateral policies by member states are disrupting the 3 trillion euros ($3.3 trillion) of annual trade inside the union as well as complicating journeys for its 450 million inhabitants.

The Tallink vessel set off earlier this week and dropped off Germans trying to get to their homeland. It also shipped a few trucks with their cargoes. On land, lines of vehicles stretching at least 10 kilometers (6 miles) on the border between Poland and Lithuania laid bare the effects of governments introducing checks at frontiers.

The threat that the virus will reinstall national borders has mobilized EU leaders in Brussels. They’ve restricted most travel into the bloc to shore up the union itself and maintain free flows of goods and people. But that strategy requires states themselves to keep lines blurred within the EU, now the epicenter of the virus outbreak with Italy the worst hit.

EU transport ministers and the European Commission agreed on Wednesday “to work closely together to minimize traffic disruptions, especially for essential freight,” according to a statement released in Brussels after a conference call. European Transport Commissioner Adina Valean demanded that corridors be established “to preserve the free circulation of goods and people who need to cross borders.”

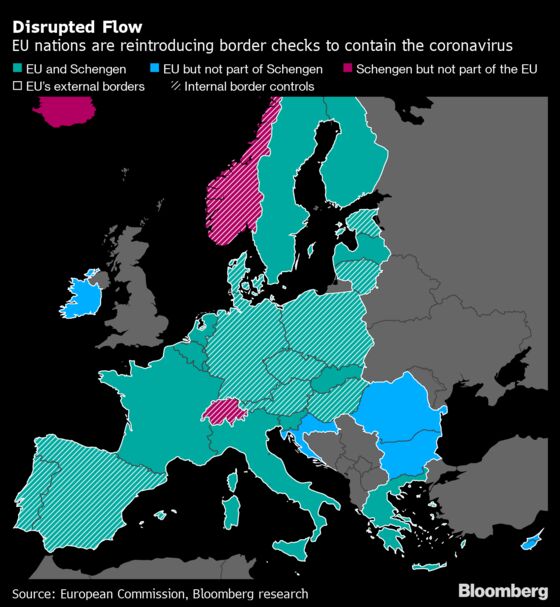

Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Poland, Lithuania, Germany, Estonia, Portugal and Spain—as well as non EU states Switzerland and Norway—notified the commission of the reintroduction of internal border controls.

While border closures are supposed to apply to people rather than goods, health checks at some crossings are causing delays, Deutsche Post DHL spokesman David Stoeppler said. Italy’s Coldiretti agricultural lobby said many truck drivers are reluctant to enter other countries for fear of not being able to return.

European crossings are in chaos, the International Road Transport Union said. Trucks account for three-quarters of the continent’s land-based freight. Without dedicated lanes, they are being caught up alongside cars, even though virus-related curbs aren’t meant to apply to them, the union said.

The bottlenecks are restricting trade just as panic-buying and hoarding by the public and businesses send demand for goods to levels normally seen only before Christmas, according to the trade group. Food and medicines are at particular risk as journeys take longer.

“It’s an unprecedented situation,” said Matthias Maedge, the IRU’s political director. “EU governments need to act together and coordinate their actions to ease the flow of goods. Long waiting times at internal EU and external borders is the main bottleneck right now. We need green lanes to ensure faster border crossing and clarity on enforcement procedures for trucks in transit.”

The conditions aren’t much easier for individuals. Residents of Ferney Voltaire, a French town on the border with the canton of Geneva, awoke Monday to find border checks had been reintroduced. That caused hours of traffic jams for “frontaliers,” who live in cheaper France and cross each day into Switzerland to work—many in hospitals.

There were issues too in Hungary, whose virus response has left thousands of Romanians and Bulgarians stuck on the border with Austria on their way home. While it opened a one-off humanitarian corridor on Tuesday, the bottleneck returned Wednesday morning after it was slammed shut again. Hungary will now allow Romanians to return home via approved routes at night after talks between the two countries’ prime ministers.

Martin Kukol, a 29-year-old advertising executive, flew back from Turkey to Vienna before embarking on the short journey home to Bratislava, Slovakia. Instead of the usual one hour, it took seven. Taxi drivers were afraid to accept him without a face mask.

“I understand these measures,” Kukol said. “But going to Vienna used to be like going to a city market. I now realize how much freedom of movement means to me.”

This isn’t the first time that the mantra of open borders has faced challenge. The refugee crisis of 2015 saw some frontiers restored as many countries were less welcoming than Germany to the flood of migrants from the Middle East.

But the principle for goods dates back to the 1960s and is such a defining characteristic of the bloc that national governments have gone to great lengths to protect it.

Brexit is the most recent example: The U.K. accepted an internal regulatory border of its own in relation to Northern Ireland as the price for leaving the EU’s customs union and protecting both the Irish peace agreement and the European single market.

There are pockets of bilateral cooperation. Lithuania’s rail operator said its Polish and German colleagues had demonstrated unprecedented speed in helping send a train from Frankfurt to the Lithuanian city of Kaunas to transport stranded local citizens. It would usually take two to three years to establish such a route. It took a day.

That’s scant hope, though, for countries outside the EU whose poorer economies rely on the bloc. The effect of border controls is painfully obvious to candidate nations in the Balkans, for which the EU is the biggest trading partner.

“Rules at border crossings are changing by the hour,” said Marko Cadez, who heads Serbia’s Chamber of Commerce. “The only concept that works against the virus is isolation and that hurts trade directly.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.