EU Companies Are Losing Hope of a Brexit Deal

EU Companies Are Losing Hope of a Brexit Deal

(Bloomberg) -- It was hard to ignore the sense of foreboding when a group of German executives logged into a remote meeting on Tuesday.

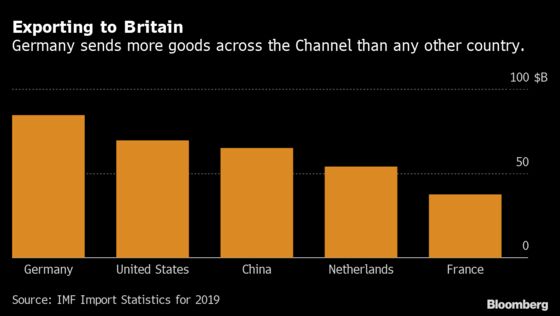

Poring over the implications of Brexit at an event organized by the economic council of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s governing party, the topics were familiar in a country that sends more goods to the U.K. than any other exporter: tariffs, logistical logjams and disrupted supplies.

But the sense of urgency reflected the reality dawning in the continent’s board rooms—from larger companies like carmaker BMW AG and Denmark’s Arla Foods to the roster of smaller firms—as talks on a trade deal between Britain and the European Union head into a critical few weeks.

During four years of political wrangling, there have been plenty of 11th-hour stays of execution for the kind of upheaval a no-deal would bring. What’s become clear to many business managers is that they can’t bank on that happening again after the U.K. said it would break international law by reneging on part of the Withdrawal Agreement signed in January.

While an accord can still happen, companies are getting ready for what many now consider their base-case scenario, stocking up warehouses and dusting off contingency plans they hoped they’d never need.

BMW, the maker of Mini and Rolls-Royce cars, has drafted plans to safeguard supplies for its Mini factory in Oxford, where some 120 trucks roll in each day, carrying parts from 400 European companies.

Aircraft manufacturer Airbus, which relies on seamless movement of goods between its sites in France, Germany, Spain and the U.K., has resumed its weekly Brexit crisis management meetings after already spending tens of millions of euros building buffer stock to avoid shortages.

In the financial industry, France’s BNP Paribas SA is moving some of its sales positions from the U.K. onto the continent as those staff won’t be able to sell services to EU clients anymore. British banks are informing some customers based in the EU that their accounts will be closed and credit cards voided.

Arla Foods, northern Europe’s biggest dairy producer, is getting anxious it will be on the hook for 100 million euros ($116 million) of losses should a trade deal remain elusive. Executives at the Danish company pressed the country’s foreign minister, Jeppe Kofod, at a meeting in Copenhagen on Sept. 15 to redouble efforts to get an agreement done.

“It's very concerning that with so little time left, negotiations seem to have stalled and trust is being eroded,” said Peter Giortz-Carlsen, Arla’s executive vice president of Europe. “We are preparing for the worst.”

Brexit may be a sideshow for politicians on the continent in the era of Covid-19, yet executives are now thrust onto the front line while they also try to cope with the shock of the pandemic on their industries.

Negotiators from the U.K. and EU meet for their final scheduled round of talks in Brussels next week. With disagreements continuing over key issues, including fishing rights in British waters and state-aid rules, officials aren’t expecting a breakthrough. That would leave two weeks to find a deal before the Oct. 15 deadline imposed by Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

No nation has more at stake than Germany, Europe’s biggest exporter. The U.K. bought almost $85 billion of goods from Germany last year, more than from any other country in the world. Some 460,000 jobs in Europe’s largest economy depend on exports to the U.K., according to Germany’s IAB labor market research institute.

The 40 participants at the event on Tuesday heard about tariffs for everything from Mercedes-Benz cars to Bayer drugs and the end of common regulation that could hit the supply chains of chemicals producers such as BASF SE.

They fretted about how to handle U.K. customer data and shipments getting snarled up from Jan. 1. The same day, the government in London warned 7,000 trucks could be lined up in England in a “reasonable worst case” scenario should no accord be struck by the end of the year. The Channel Tunnel rail link could also see “significant disruption” if an argument over its jurisdiction isn’t resolved, according to a report by U.K. lawmakers this week.

The car industry is especially affected. Germany’s VDA trade group also convened this week, holding a two-hour virtual conference to brief members on topics including tariffs, logistics and the freedom of movement of workers.

The European auto industry would lose about 110 billion euros in trade through 2025 in case of a no-deal Brexit, two dozen of the region’s auto industry groups said last week. The damage would come on top of about 100 billion euros of production lost this year when the coronavirus shuttered factories and showrooms, they said in a joint statement.

With no deal in place by the end of the year, companies would have to trade under the World Trade Organization’s non-preferential rules, which include a 10% tariff on cars and up to 22% on vans and trucks—fees that are far higher than the margins of most manufacturers. Swedish truckmaker Volvo Group said it’s continuing preparations to trade on those terms.

When BMW assembles a Mini in Oxford, it uses parts from all over the continent, including windshields made in Germany and headliners from Italy. Eight in 10 Mini and Rolls Royce cars built in the U.K. are exported, more than half of those to EU countries. That means BMW could faces tariffs on parts going in and then cars going out.

Nerves are also fraying at many export-focused Mittelstand companies, which form the backbone of the German economy. In recent weeks, they sought more advice from the British Chamber of Commerce in Germany, said Ilka Hartmann, who heads the group.

“The insecurity weighs down everyone,” she said. “Chances for a meaningful agreement that’s more than just an emergency measure are getting slimmer with each passing day.”

Sortimo International GmbH, which employs about 1,800 workers, most of them in Germany, produces racking systems to convert regular vans into service vehicles. Sortimo generates about a fifth of its 250 million euros in yearly sales in the U.K., where it employs about 70 people and caters to customers including British Gas and Scottish Water.

The company set up a task force with four or five specialists who meet once a week. While the group focused almost exclusively on dealing with the coronavirus pandemic during the spring and early summer months, discussions have now shifted back to Brexit.

Sortimo has stocked up its soccer-field-sized warehouses near Manchester, northwest England. The company had even mulled building up production capacities in the U.K. because of the looming threat of tariffs, but shelved that plan when the pandemic curbed demand. Sortimo is now pursuing cost cuts to make the company more resilient as two worst-case scenarios look like they’re here to stay, said Reinhold Braun, the firm’s managing director.

“The economic hit from the corona lockdown exacerbates the difficulties of a hard Brexit,” Braun said. “The combination of the two makes future business virtually impossible to predict.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.