To Escape Lockdown, Don't Be Creepy With Health Data

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The most important trait of any Covid-19 contact-tracing app is that people actually use it. Without widespread adoption, we may all be locked down for a lot longer.

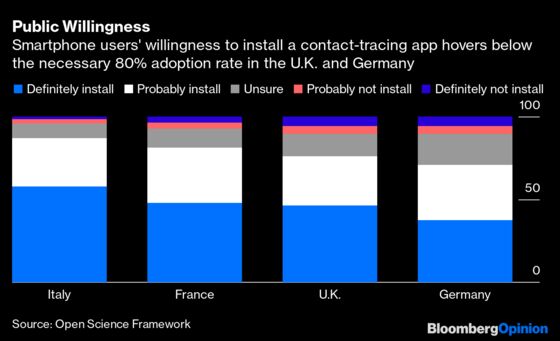

Just how widespread? In the U.K., at least 80% of smartphone users, covering 56% of the total population, will need to use the app to be effective in tracing contacts with those infected to control the novel coronavirus’s spread, according to an April report led by Oxford University’s Nuffield Department of Medicine. Winning popular trust has to be the priority.

Unfortunately, Britain’s National Health Service seems to have gotten off on the wrong foot with the solution it started trialing on the Isle of Wight, off England’s southern coast, on Tuesday. The app has caused concern about the centralized collection of information. Even though it’s anonymized, and less specific than the location data that many happily share with Google Maps or running apps such as Strava (the NHS app just asks you to identify your district), the fact it’s a central repository of health data, with little clarity on who exactly holds it and for how long, has people in a tizzy.

Don’t get me wrong. The app appears thoughtful, seeming to keep user anonymity and privacy in mind, while providing health authorities with useful data for the epidemiological models developed to manage the pandemic in the U.K. But all of that becomes moot if people don’t use it. Public opinion is fickle, and if people perceive this as a tool for government monitoring, then adoption will suffer. There are also questions about how it will interact with other nations’ approaches, affecting the prospects for international travel.

Here’s how it works: Once someone reports symptoms that suggest they have the virus, their phone will share anonymized data about who they’ve been in contact with and for how long (it uses smartphones’ Bluetooth chips to detect whether people have been within six feet of each other for 15 minutes) with a central server operated by the NHS. Those contacts are then alerted by the server, and told to self-isolate. Doing it this way might help the NHS understand how many people the infected have crossed paths with and identify trends, making it easier to predict any new flareup. By identifying those with symptoms, rather than simply those who have tested positive, it’s trying to get ahead of the infection curve.

I trust the NHS to use my data, which will be anonymized, responsibly. But it’s possible not enough other people will. An April survey of potential app users in the U.K. suggested that 74% would be likely to download a contact-tracing app, short of the 80% necessary.

Beyond the privacy concerns, however, there’s a technological weakness that may be more significant in denting the app’s efficacy. The NHS solution seems to require that when two people are in close proximity with each other, at least one of the them has to either have the app open, or to have opened it in the past few minutes. If that’s not the case, it won’t log the contact. A spokeswoman for the health agency told the BBC last month it was satisfied that the solution worked “sufficiently well.” We’ll soon know: The Isle of Wight trial ought to reveal any shortcomings.

It’s reassuring that there’s an alternative solution available developed by privacy advocates as well as Apple Inc. and Google, who between them make the operating system for almost every new smartphone on the planet. It takes a decentralized approach. Rather than passing data up to a central server, the Apple-Google app broadcasts the unique anonymized identifiers of those who have the virus to the other phones using the app. Those smartphones then tally the identifiers against the list of handsets with which they have crossed paths in the past 14 days, and alert the user. The other advantage of the tech giants’ approach is that phones will always be able to exchange identifiers in the background via Bluetooth.

That’s the method already being pursued elsewhere, including in Austria, Switzerland and Germany. Germany is notable because its approach underwent a radical reversal: It had initially favored a centralized model, then changed course after public uproar.

I understand why the NHS is, like France, pursuing the centralized approach. More data will help it manage the crisis better. I sincerely hope it works, and it can convince people to stomach their privacy concerns. But if it doesn’t, and they don’t, then Britain’s health service needs to be prepared to pivot, and quickly, before public opinion is poisoned against any app.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alex Webb is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Europe's technology, media and communications industries. He previously covered Apple and other technology companies for Bloomberg News in San Francisco.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.