(Bloomberg Opinion) -- February is almost here, and with it, the first tipple in weeks for people who have been briefly abstaining for "dry January."

A month of sobriety can be a valuable opportunity to examine a relationship with drinking. Unfortunately, these 31 days are one of only a few times in the year when there is national attention directed at alcohol use, even as it continues to be a significant public health issue.

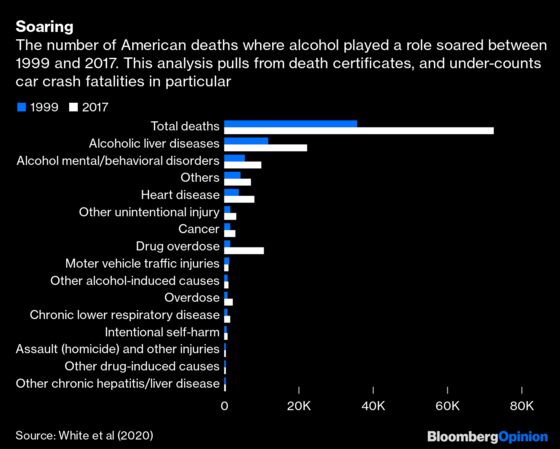

The number of annual alcohol-related deaths in America more than doubled to 72,558 from 1999 to 2017, according to a recent study. Many of those deaths are inherently preventable, but there are limited efforts in the U.S. to enact the sorts of policies required to head them off. That’s something worth focusing on for more than a few weeks.

Plenty of people enjoy alcohol without problems, and some studies find that drinking in moderation can deliver health benefits. The industry creates significant employment at businesses large and small, not to mention products that can be both delicious and culturally significant. So prohibition isn’t a good or realistic answer. But statistics show that there are plenty of individuals for whom alcohol is a problem, and the health risks of even mild overuse are clear enough that efforts to at least reduce consumption are worthwhile.

Smoking, an even more significant cause of preventable death and illness, has dropped in recent decades after years of effort to the point where it's having a positive impact on cancer mortality. While there are plenty of trend pieces on lower alcohol consumption by millennials, it hasn’t shown up in population-level statistics. In fact, after years of decline, America’s recorded use has been gradually ticking up since the late 1990s.

The actual number of alcohol-related deaths is likely higher than public data suggests, because alcohol's role isn't always noted. In addition to contributing to accidents, crime, violence, and liver disease, drinking increases the risk of heart disease and several cancers. Even the above cited figure, which is on the conservative side as it’s pulled from death certificates, puts America’s alcohol-related deaths in 2017 ahead of those caused by influenza or pneumonia. A higher estimate of 81,000 deaths in 2017 from the World Health Organization suggests alcohol may be a bigger killer than diabetes. And the human and economic cost extends far beyond the number of people who die in any given year.

There are plenty of cost-effective opportunities to treat alcohol abuse like the public health problem it is — the World Health Organization highlights increasing taxes, regulating physical availability, and restricting exposure to advertising. These don’t sound like they would do a lot. But over time, such measures can cut consumption and harm, particularly for younger and heavier drinkers. High cigarette prices, indoor and general smoking bans, and marketing regulations have played a substantial role in reducing smoking. The U.S. has made inconsistent progress on such measures when it comes to alcohol, however, and doesn’t seem to be pushing to do more.

Americans aren’t much for consumption taxes, and alcohol is no exception. While policy varies by state, the average tax per hectoliter of absolute alcohol is among the lowest in the OECD, though some countries are more lax on beer and wine.

Regulation is a mixed bag. America does have a higher drinking age than many nations, but a majority of countries set permissible blood-alcohol content for drivers below the U.S. standard of 0.08%. Regulation of how and when alcohol is sold is an asystematic hodgepodge that varies by state and even municipality. Only America could have dry counties where alcohol is entirely unavailable and others where you can buy a high-octane frozen daiquiri at a drive-through store. Restriction on alcohol advertising is also scant relative to many other developed nations and relative to tobacco.

Access to smoking-cessation aids also has been a big help in lowering tobacco use. Treatment remains an area where the U.S. is notably ineffective when it comes to alcohol, however. Relatively few people that abuse alcohol get treatment at all, and effective medications that can curb abuse are significantly underused due to limited availability and unfortunate stigma.

You’d have to work hard to think of policy changes less popular than boosting alcohol taxes and making liquor harder to obtain. At the end of the day, however, they represent only a modest burden on moderate drinkers. Dry January focuses on individual improvement and growth. A broader conversation about alcohol regulation could do far more to help the country as a whole — especially when a relatively small measure such as a boosted alcohol tax could even help cover the cost of more expensive initiatives.

None of this is to say that people who made it through the month shouldn’t enjoy a few cocktails this weekend. But after a couple of weeks off the wagon, it might be time to consider whether there’s a need, after a Free-Flowing February, for a Must Rethink Alcohol Policy March.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Max Nisen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering biotech, pharma and health care. He previously wrote about management and corporate strategy for Quartz and Business Insider.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.