Drones and AI Ward Off Shark Attacks as Predators Hunt Closer to Shore

Australian technology designed to avoid killing animals arrives amid warming oceans that make human-shark interaction more likely.

(Bloomberg) -- Can technology protect you from the jaws of a one-ton great white shark?

Several Australian tech startups say yes. They’re using artificial intelligence, drones and electric force fields to try and prevent sharks from eating human bathers.

Officials in the U.S. are watching the technological advancements keenly, aware that climate change is altering shark migration patterns and threatening to push great whites ever closer to U.S. shores. This summer, sharks have attacked teenagers on beaches from California to New York.

Sharks have typically frequented lower latitudes, but warming oceans are pushing their prey north, says Florida Atlantic University Professor Stephen Kajiura. Apex predators at the top of the food chain, sharks will always follow their nourishment, he says, which means they’re moving into new terrain, including America’s northeastern coast.

“We are very aware of how close to shore great whites are now hunting,” says Cynthia Wigren, chief executive officer of the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy. Two weeks ago, a 26-year-old boogie boarder was killed by a shark in the first fatal attack in Cape Cod in 80 years. Wigren, who lives there, immediately started looking for new technology that could help prevent future attacks; her research led her Down Under, where a surfing culture, a long coastline and beach tourism have prompted a search for ways to prevent shark-human interaction without resorting to killing the animals.

Last year, 16-year-old New South Wales high school student Samuel Aubin designed a smart phone app called SharkMate that uses AI to analyze 13 environmental factors that affect shark behavior, including time of day, proximity to a river and recent rain. These are combined with other data, such as the number of lifeguards on duty, to calculate the odds of being attacked.

In January, the Ripper Group, which operates search and rescue drones in Australia, launched SharkSpotter, a deep learning computer program that scans the ocean for sharks from the air. The AI algorithm detects the animals based on their movement, speed, color, texture, shape and swimming patterns. When it spots a shark, the drone sends an alert to lifeguards and can drop inflatable devices to swimmers in immediate danger. The drones were operating along 15 beaches in New South Wales last summer, and CEO Eddie Bennet says they’ll patrol an additional 50 beaches this summer as more lifeguard associations jump on board. He plans to go public next year.

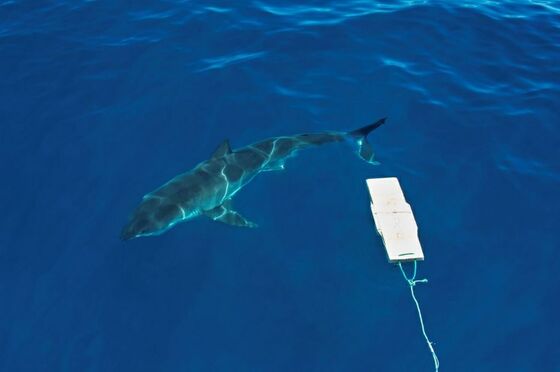

SharkMate and SharkSpotter try to influence human actions; Ocean Guardian’s Shark Shield attempts to change the animal’s behavior. The electric transmitting device emits a three-dimensional force field that causes unbearable spasms in a shark’s sensory systems, prompting the animal to turn away from its prey.

The portable device retails for about $500 and can be worn on the ankle of a diver, glued to the gripping pad of a surfboard or stuck on the bottom of a boat. Researchers have analyzed hundreds of encounters between a baited decoy and sharks, including 13-foot great whites, and determined in peer-reviewed research papers that the Shark Shield is the world’s only scientifically proven electric shark deterrent.

Several leading shark researchers back the three technologies and predict that a combination of drones and AI will obviate the need for the shark nets that have cordoned off swimming beaches to the detriment of marine life for almost a century.

The three startups are all run by conservationists who aim to not only prevent sharks from mauling humans, but to stop humans from shooting sharks in retaliation. Six sharks were captured and shot in Australia’s Whitsunday Islands in a controversial operation led by the Queensland Government after a 46-year-old woman and 12-year-old girl were bitten within the space of 24 hours earlier this month.

People have had an irrational fear of sharks ever since Jaws, the 1975 blockbuster. Public fascination with these predators means every attack makes headlines, regardless of how minor the injury.

While unprovoked attacks are exceedingly rare, they have been climbing since the 1970s, as protected white shark populations return to historic levels, outdoor water sports grow increasingly popular and countries become more vigilant about reporting incidents, says Dr. Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research. However, the media’s obsession with shark attacks is warping reality, he says. Naylor oversees the International Shark Attack File and confirmed the number of attacks this year is below average. In 2017, there were 88 unprovoked attacks worldwide and so far this year there have been only 40, he said.

The “sensational reporting,” he says, stokes irrational fear and can cripple tourism. Every time an attack occurs in Australia, the county’s $120 billion dollar tourism industry takes a hit. The authorities are keen for the anti-shark startups to succeed so they can stop culling the animals and protect the public and economy.

The Australian government has provided a funding grant to Aubin’s SharkMate app, to help the teenager roll the program out across the country’s 150 beaches, along with the help of the University of Wollongong’s shark monitoring program. It is also offering $200 rebates to those who buy a Shark Shield from Ocean Guardian. But despite government backing and five peer-reviewed scientific research papers, consumers aren’t biting.

“It’s hard to convince people you can stop a one-ton great white shark moving at 30 kmh from eating you, but it does,” says Ocean Guardian CEO Lindsay Lyon, who scrapped an initial public offering last year but plans to try again in 2019.

Even British daredevil Bear Grylls couldn’t bring himself to fully trust the technology. In July, he covered himself in fish guts and blood for Discovery Channel’s Shark Week, tied a Shark Shield to his ankle and slid (without cage) into the shark-infested North Atlantic. “I’m marinating in fish guts at their feeding time,” Grylls said.

As giant bull sharks circled, he said: “This may have been a bad idea.” When Grylls turned on the device, it appeared to repel the sharks. But with visibility worsening and more sharks arriving, Grylls lost his nerve and retreated before the animals got any closer.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robin Ajello at rajello@bloomberg.net, Molly Schuetz

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.