Does Talk of Covid Dividend Make Any Sense?

Does Talk of Covid Dividend Make Any Sense?

(Bloomberg) --

You might have thought Covid-19 was done teaching the world a lesson — but it’s not done challenging long-held assumptions in economics. We had to give up believing in the resilience of modern supply chains some time ago, and the strength of inflation has central banks rethinking their theory of prices by the day. Now, the very pace of recovery in some parts of the world has many wondering whether the Covid recession in the U.S. will be the first in history to leave the economy better off than it was before.

It’s a tantalizing thought. In some advanced countries it does look as though the pandemic has done less long-term damage to the economy than initially feared. Over time, the U.S. economy might even end up ahead. But hopes of a hefty “pandemic dividend” for productivity or investment in the U.S. seem rather optimistic — especially if supply disruptions turn out to be prolonged. The former head of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors, Jason Furman, came to the same view in a recent interview for Stephanomics. What’s clear is that Covid has deepened pre-existing inequalities, within countries and between them. Policymakers seem well behind the curve in their response.

Dan Hanson and Yelena Shulyatyeva examined 36 recessions since 1965 for Bloomberg Economics and found that 90% of the time, economies that suffer a downturn never get back to their pre-crisis path. The average hit was 4.7% of gross domestic product, with deeper recessions typically producing more long-term damage.

In the thick of the pandemic, this historical record didn’t bode well. Economic lockdowns had produced double-digit declines in output in many economies by the middle of 2020 and an historic 3.3% decline in global GDP for the year as a whole. (For reference, global output barely fell at all in the 2008 financial crisis.)

There were, however, some distinctive features of the pandemic that led to hope that the outcome might be much brighter: notably that the financial sector wasn’t caught up in the crisis or making it any worse. Even more important, governments stepped in almost immediately to “fill the hole” in GDP left by lockdowns. In the case of the U.S., household incomes actually rose in 2020, despite an historic decline in U.S. output in the first half of the year.

Globally the International Monetary Fund puts the long-term damage at about 3% of global GDP. That’s a palpable hit, but as the IMF points out, the global financial crisis of 2008-9 left a much larger hole of close to 10% of global GDP. The headline 3% number also hides enormous variation.

For the U.S., the speed and continued scale of the fiscal supports have seemingly prevented any long-term harm to GDP, an astonishing outcome. Bloomberg Economics expects the U.S. economy to be back on its 2010-19 trend line by 2023.

Others haven’t been quite so fortunate, but as Ziad Daoud and Scott Johnson point out, emerging market economies returned to their pre-Covid level of output by the end of the first quarter of 2021. That’s a turnaround of 7.6 percentage points of GDP in barely nine months. On average, the IMF estimates that the longterm cost of Covid-19 for emerging market economies will also be about 3% of GDP. But for lower income countries that didn’t have ready access to vaccines or fiscal capacity to support the economy, Covid-19 could bring more long-term harm than the recession of 2008-9.

That’s the big picture on the crisis. At the micro level we know the pandemic also kick-started a revolution in work practices and greatly accelerated the use of technology and automation in many advanced economies.

In the peak of the initial U.S. lockdown the equivalent of almost two-thirds of GDP was being generated by people working from home, and many retailers went from having no online presence to selling almost as much as before the pandemic, entirely online — in a matter of weeks.

Some think this holds out the possibility of not just minimizing the permanent hit to GDP, but actually coming out the other side with a faster rate of potential growth. The McKinsey Global Institute, for example, reckons that the faster automation and change in work practices could raise productivity growth in the U.S. and Western Europe by about one percentage point annually in the years to 2024, double the pre-crisis average.

That would be an extraordinary outcome. Can it really be true that some advanced economies will grow faster as a result of Covid-19?

Going back to basics, it’s the growth rate of core inputs — labor and capital — and the efficiency with which they’re used that drives the long-term potential growth rate of an economy. Recessions don’t change the growth rate of the population, and neither has Covid-19 in any significant way. But workers being made unemployed will damage a country’s human capital, especially if unemployed workers take time to find new work, end up in lower quality jobs, or leave the workforce altogether.

When output is falling, businesses tend to cut back on capital investment and innovation. Economies get back to their previous level of output, but the forgone investment and innovation is never entirely made up, meaning the economy is on a permanently lower path.

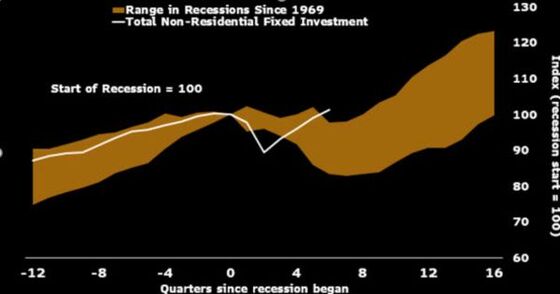

The path of investment definitely was different in this recession. Business investment has recovered more quickly than any U.S. downturn going back to the 1960s as the chart below illustrates. The bounce was even greater for equipment investment — no doubt partly thanks to that jump in automation and a revolution in working practices. Data from the Robotic Industries Association shows spending on robots was 64% higher in the fourth quarter of 2020 in North America than a year earlier.

Faster Recovery in U.S. Business Investment

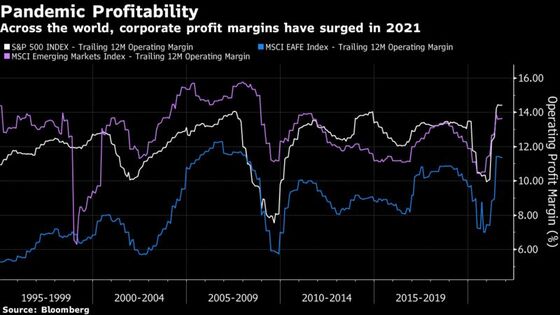

If investment stays on a higher growth path in 2022 and beyond, that could produce a positive Covid dividend, other things equal. And businesses in the U.S. and the eurozone certainly have money to spend after a year of stunning growth in profitability and returns (see chart below).

Alas, it is far too early to say whether that kind of boom is taking place. Although the advanced economies as a group have seen investment bounce back much faster than in 2008-9, the total amount is still below the pre-crisis trend. Also, there’s been plenty of cash sitting on corporate balance sheets in other recent periods without it translating to significant growth in investment. Quite the opposite.

Business investment has tended to fall as a share of GDP in advanced economies in recent decades. We have mostly attributed that slowdown to long-term structural factors, including the declining cost of investment goods and the aging of the population. Covid-19 hasn’t done anything to change those.

Most important, other things are not equal. Even if investment and productivity are booming in parts of the economy, that’s not the story for the whole economy or the wider world. Looking at the severe labor and supply shortages in the U.S. and other countries, the economy-wide disruption and dislocation across the economy caused by dislocations of labor and output on the scale we have seen in the past 18 months have manifestly inefficiencies and adjustment costs along with that short-term bounce in profit margins.

We also know that what’s life- and productivity-enhancing for the roughly half of the workforce who were working from home through the pandemic could have the opposite impact on workers in high-contact sectors who were the first to lose their jobs when economies were shut down.

As a recent academic paper points out, high-skill service workers in the U.S. may now have more flexibility in deciding where to live, but that in turn endangers the livelihood of low-skill service workers in big cities who depend on local consumer demand.

The unequal distribution of gains and losses within countries will be mirrored, if we’re not careful, by divergence at the global level — as countries not well placed to weather the changes in the global economy slip further behind the rest.

Bottom line: Covid-19 is going to do less permanent damage to the size of the global economy than initially feared and by disrupting old ways of doing things, may well have boosted productivity and innovation in key sectors. That is good news. But these same forces are also threatening to make wealth and income inequalities even more entrenched. There was a lot of talk, in the thick of the crisis, about promoting inclusive growth and a “reset for workers.” Looking at the rather bumpy recovery we’re seeing around the world, it is far from clear that governments know how to make that happen.

Read more:

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.