Does Focusing on Manufacturing Make Sense for the U.S.?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As part of her campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, Senator Elizabeth Warren has proposed a broad effort to revive and expand American manufacturing. Bloomberg Opinion columnists Karl Smith and Noah Smith met recently online to debate her proposal.

Karl Smith: Noah, from what I can tell you’re a fan of Warren’s Economic Patriotism platform and you’ve written yourself in favor of industrial policy. My concerns are essentially two-fold. First, I think that given the U.S.’s strength in what we might call knowledge industries such as tech, biotech, fracking and finance, it's going to be difficult for U.S. manufacturing to thrive as a major employer.

Second, although industrial policy has a fantastic track record bringing countries to the technological frontier, it is precisely on the frontier where industrial policy is dangerous. Is it really possible or desirable for the U.S. government to predict the next winners in clean energy, or choose the right structure for U.S. retail or global social media?

There is room for more infrastructure spending, especially with interest rates this low, but that should be done with eye toward boosting the entire range of economic possibilities rather than picking a specific -- necessarily manufacturing-centric -- approach to U.S. growth.

Noah Smith: First of all, I don’t see manufacturing as a big source of employment -- it will be increasingly automated. Instead, it has other benefits. First, advanced manufacturing is itself a knowledge industry, just like software or biotech. Second, manufacturing helps attract other parts of the supply chain -- it’s cheaper and easier to design things and sell things closer to where those things are made. This is probably why economists Ricardo Hausmann and Cesar Hidalgo founnd that the more different kinds of products a country makes, the faster it tends to grow.

And third, manufactured goods are easy to export, which helps not just the country but also the cities where the products are made. Economist Enrico Moretti found that every high-skilled manufacturing job in a city generates about 2.5 jobs in the nontradable sector (retail, construction and so on) in that same city.

As for industrial policy, I’m glad we’re in agreement that it’s useful for countries catching up to the technological frontier, and that it’s harder for rich countries to pick the winning industries of tomorrow. That’s why Warren’s plan focuses on research and infrastructure. But I think there is also a strong case for export promotion, which pushes domestically focused companies to enter more competitive global markets.

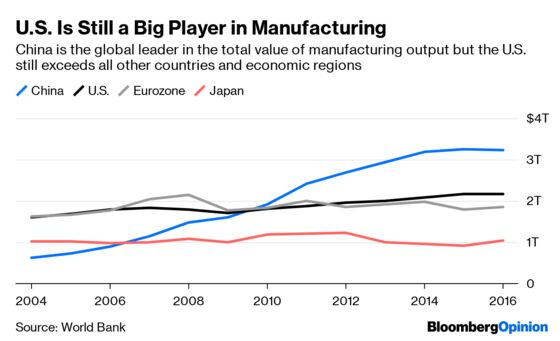

KS: I agree with you that American manufacturing is likely to be advanced and highly automated. Yet, this does not appear to be what Warren has in mind. She explicitly criticizes those who blame automation for the decline of manufacturing jobs and points to Germany as a positive example of a nation that has maintained jobs despite deploying five times as many robots per worker as the US. In terms of value of manufacturing produced, the U.S. may be second to China, but it's far ahead of the rest of the world, including Germany, Japan and the entire eurozone.

Further, while she would put $400 billion into a Green Apollo Program, she would put four times as much into a combination of buy-America provisions and export subsides. These are exactly the type of measures we’ve criticized President Donald Trump for making in regard to the steel and aluminum industries.

As for the Green Apollo Program, it prioritizes research and development that can be commercialized rather than basic research and is explicitly geared towards sectors that are under-represented in green technology. That’s sounds like an explicit promise to pick and develop winners that would otherwise not be commercially viable.

To be blunt, Warren repeatedly uses the defense industry as a model, suggesting that the creation of an energy-industrial complex is precisely what she has in mind.

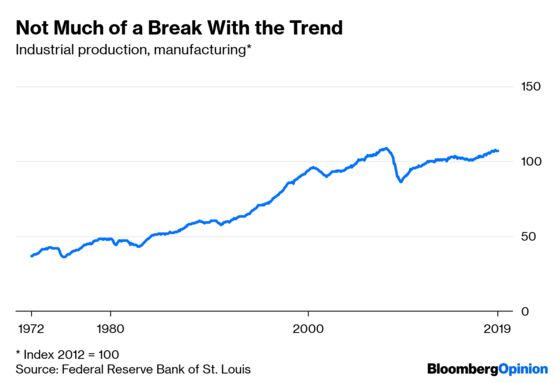

NS: First of all, total numbers can be deceptive -- although the U.S. is a big manufacturer, its manufacturing sector is only 12 percent of its economy, compared to 21 percent for Germany and Japan and 28 percent for South Korea. A more worrying statistic is industrial production in manufacturing, which has flat-lined since the turn of the century:

Also, I’d hold off on criticizing the type of research Warren would fund. The so-called DARPA model or ARPA model -- multidisciplinary, mission-driven research into promising emerging technologies -- has proven extremely effective in the past. I love basic research too, but it’s a long-term thing, and we need new technologies right away.

KS: The DARPA model was impressive, but I strongly doubt that it’s replicable, particularly in the context. Indeed, Pierre Azoulay, et al. emphasize that DARPA was at its best in high-risk, high-reward ventures chosen at the discretion of the scientists and engineers involved. That makes it difficult to produce the type of targeted and accountable change that Warren's plan is looking to produce.

Furthermore, the era of big rewards from writing blank checks to smart scientists has likely passed. As Michael Mandel has pointed out, Bell Labs made extraordinary progress during that era largely because of the freedom and lack of accountability that ATT’s monopoly status afforded its researchers. Google’s dominance has afforded its researchers a similar latitude. Although in the long-term they may fundamentally change the way we work and live, their near-term results have been underwhelming.

Lastly, as you correctly point out, the need for green energy advances is urgent. That means we are more likely to have luck with carbon prices or low-carbon production credits that reward increased deployment of clean energy no matter what technology it uses or where in the world that technology is created.

NS: I agree that we need incentives to expand existing low-carbon energy technology. Solar, wind, batteries and other energy storage will be key, as well as the electrification of home heating and cooking. This is where the biggest gains will come from in the fight against carbon.

But we can always use better and more diverse options for energy storage and we need to create better low-carbon production processes for cement and steel. That's what mission-driven research like DARPA did -- where government decides the goal and scientists and project managers decide how to get there, will probably be the most effective.

Manufacturing is still important, though not for all of the same reasons it was important a century ago; export-oriented industrial policy is smarter and more promising than picking winners; and big expenditure on DARPA-style green technology research is extremely promising. Thus, despite some missteps like “buy American,” I like Warren’s plans.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Karl W. Smith is a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina's school of government and founder of the blog Modeled Behavior.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.