Deripaska’s Hard Times Help Oligarch Weather Trump Sanctions

Embattled metals tycoon has been damaged by his battle with Washington, but his key businesses remain in tact.

(Bloomberg) -- Oleg Deripaska’s rise from a small Soviet village on Russia’s southern steppe to billionaire commodities tycoon was rarely free from conflict.

He emerged from the all-too-literally-named aluminum wars of the 1990s with his nascent business empire in tact, won legal battles over embittered rivals and disgruntled partners alike, and fought off near-bankruptcy during the global financial crisis.

But when the Trump administration slapped Russia’s aluminum czar and his most important companies with aggressive sanctions in April -- sending global metal markets into a tailspin in the process -- many thought he faced a foe he’d struggle to beat.

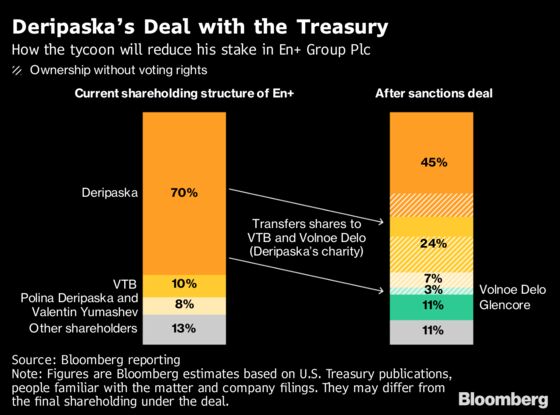

Eight months later and Deripaska seems to have achieved, at the very least, a partial victory. While the U.S. Treasury’s unprecedented foray into the heart of Russia’s business elite forced him to give up direct control of the country’s largest aluminum producer, he remains the biggest shareholder. Longstanding allies hold many of the remaining shares.

Deripaska believes he's been hurt by sanctions (measures against him as an individual remain in place), but the 50-year-old sees freeing United Co. Rusal and holding company En+ Group Plc as a big gain, an acquaintance said, asking not to be named discussing private conversations. A spokeswoman for Deripaska declined to comment for this story.

“This is a hard task for Deripaska,’’ said fellow billionaire Vladimir Yevtushenkov, who had his own reversal of fortune in 2014 when he was placed under house arrest in Moscow and forced to give up his oil company (even though the charges were dropped.) “Rusal is his baby and he’s at risk of losing his influence. This is a tragedy for him, but he’s fighting.”

When the U.S. first announced sanctions against a range of Russian targets in April -- responding to Congressional pressure to get tougher with Vladimir Putin’s regime -- it convulsed global markets. The ruble plunged, Rusal dropped more than 50 percent and aluminum prices skyrocketed.

Inner Circle

The sanctions left Rusal unable to sell aluminum outside Russia or buy key raw materials. As his inner circle scrambled to respond, Deripaska, who’d had billions wiped from his net worth in a single day, tried to project calm.

"I am preparing to celebrate Orthodox Easter," was his first public response.

In private, the 50-year-old was determined to ensure his business empire survived. He started lobbying European diplomats, explaining the sanctions threatened to jack up costs in industries from aerospace to brewing. His team also reached out to Rusal's biggest clients to ensure they'd help campaign against measures that had quickly become a threat to the supply chains of industrial giants from BMW AG to Airbus SE.

That effort helped win a temporary reprieve. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said America has no quibble with the 60,000 people who worked for Rusal, or the companies that bought its metal, and the U.S. delayed the sanctions enforcement seven separate times to make time for negotiations.

By June, Greg Barker, an English politician who chairs Deripaska's holding company En+, had enlisted investment bank Rothschild & Co. and lobbyist Mercury LLC to help manage talks with Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control.

Deripaska was even feeling confident enough to rebuff an opportunity to refinance debt with state-run Promsvyazbank because the terms weren't attractive enough.

Through all the turbulence, he never worried he was ruined, according to several people who know him. His attitude was “If I’m going down I’ll be taking a lot of other western businesses with me,” one of them said.

"It’s not that Deripaska came out of the battle against sanctions unscathed, but the main thing is that he's still in the game," said Kirill Chuyko, chief strategist at Moscow stockbroker BCS Global Markets and a long-time follower of Russia’s metals industry.

His fightback is typical of a man whose checkered career shows a rare ability to survive the treacherous political and business currents of post-Soviet Russia.

Small Village

Born in 1968, Deripaska was raised by his grandparents in a small village in the Krasnodar region, a place he still supports financially. After school, the talented teenager was admitted to study Physics at the prestigious Moscow State University, where he met some of his future business partners. After a stint in the army, he graduated with honors in 1993.

Moscow University at the time was like a trading floor, one of Deripaska’s classmates said. Many students, trying to survive the post-communist economic turmoil, were starting their own businesses. Fellow billionaire Andrey Melnichenko, who was couple of years behind Deripaska, began trading currency with two friends while a student. Deripaska chose metals trading.

Deripaska became very rich long before Vladimir Putin became president. As early as 1994, he'd gained a stake in the Sayanogorsk aluminum smelter by buying shares from the plant's workers. By the time Boris Yeltsin appointed Putin to be his successor in 1999, Deripaska, still just 31, was already one Russia’s most prominent businessmen.

He later married Polina, the daughter of Valentin Yumashev, Yeltsin's son-in-law and former chief of staff. The union provided Deripaska's the only direct link with Putin because the Russian president still protects the Yeltsin family’s interests, according to two people familiar with the situation.

Deripaska had already emerged from the so-called aluminum wars of the late 1990s, where several factions fought for control of Russia's aluminum industry, in a strong position. In 2000, he joined forces with fellow oligarch Roman Abramovich to form Rusal and three years later bought out his fellow oligarch out of the business.

Visa Trouble

Meanwhile, Deripaska had to fight multiple claims in international courts from former partners, patiently settling them one by one. Some of the claims submitted in the U.S. courts argued that Deripaska had links to Russia's mafia, a theme that the U.S. Treasury used when sanctioning him. The magnate was denied a visa in 1998 and has had difficulties obtaining the right to visit America since then, he said in a 2011 interview.

After acquiring a range of business inside and outside Russia in the early 2000s, including one of of the world’s largest car parts manufacturers, Deripaska confronted the 2008 financial crisis heavily indebted and in order to meet margin calls from bankers he gave up many of his assets.

But just like this year, Deripaska was able to save his crown jewel, Rusal. He had to put the company through a $17 billion debt restructuring in 2009, the largest in Russian corporate history, and he personally oversaw negotiations with more than 70 banks.

The U.S. will be satisfied it's managed to loosen Deripaska's control of Rusal, but the company has survived again and one of Russia's most controversial businessmen remains the largest shareholder.

"The fact that he managed to free his business from the sanctions is remarkable," BCS’s Chuyko said.

--With assistance from Jack Farchy, Irina Reznik and Andrey Biryukov.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Will Kennedy at wkennedy3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.