The Unnerving Mystery of a $6.6 Trillion Dead Calm

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Here is a puzzle that is preoccupying the world’s currency dealing rooms.

No market is more liquid and nothing is more heavily traded than foreign exchange. The latest survey by the Bank of International Settlements, carried out in April, showed that total currency volumes traded per day reached $6.6 trillion (yes, trillion with a t). In fact, while other markets remain quieter than they were before the global financial crisis, foreign exchange volumes have more than doubled.

Add to this that the world has been roiled for 18 months now by the most serious trade conflict to involve the U.S. since the current currency regime came into being with the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971. Tariffs and threats of tariffs normally imply an immediate response from the currency markets to try to offset them. With vast sums of money changing hands every day, this should be a recipe for big lurches and high volatility such as hasn’t previously been present.

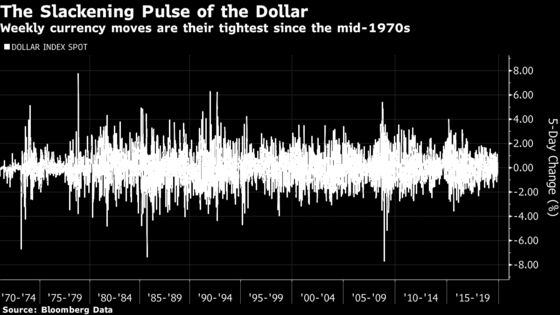

And yet, volatility is the lowest since the earliest days after Bretton Woods. If we take a simple measure of five-day percentage moves in the dollar spot index (comparing it to other developed-market currencies), we find that there hasn’t been a weekly swing of as much as 2% in almost two years. The last time this happened was in 1976.

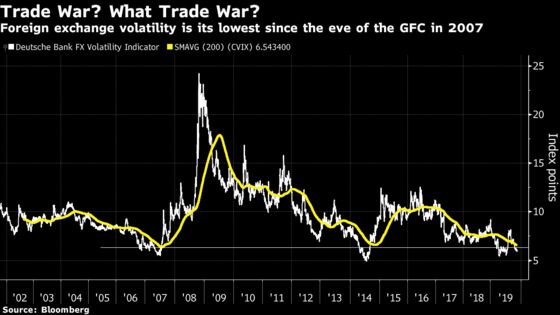

Looking at implied volatility, foreign exchange as an asset class hasn’t been this calm since mid-2007, at the end of the period know as the Great Moderation before the financial crisis, when volatility across a variety of asset classes was artificially low:

To take one final measure, the spread between the highest and lowest level for the dollar index over the last 12 months is now below 5%. Again, this is the lowest since the very different days of 1977, when a number of the biggest U.S. trading partners still had tightly controlled currencies. And while the dollar remains the linchpin of the global financial system, plenty of major pairs that don’t involve the greenback also show very low volatility. This is a global effect.

How can foreign exchange be so calm at such a turbulent juncture for international trade? One field of explanations covers the macro. The Federal Reserve executed a U-turn at the turn of the year and cut rates, thus heading off concerns that it would over-tighten — something that can reliably expand volatility. There is now a deal of comfort over the Fed’s course for the foreseeable future: It won’t be raising at all, and it won’t be cutting much. Meanwhile, other big central banks are also easing, giving little compelling reason to shift between currencies. In all cases, bets on central banks are asymmetric; they could ease but they won’t tighten. And global economies are sufficiently linked that if one has to ease, others will probably do the same.

And while trade conflicts may be adding to the sources of volatility, changes in the oil market have taken away one critical source of turbulence. With the rise in supply from outside OPEC, even a major Middle East story such as the drone attack on a major Saudi Arabian oil installation earlier this year had little effect on the currency market.

There are also some micro factors. Bonds and stocks also show very low volatility, if not the historic lows seen in foreign exchange. Hedge funds have placed heavy bets on volatility to stay low, and this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Plus the sheer liquidity of foreign exchange does have the effect of ensuring against sudden stops or extreme moves in response to news.

But there’s no question that investors and officials find such low volatility unnerving. Since the crisis, many have re-read the works of Hyman Minsky, who held that financial stability generates instability, and there are painful memories of the way the last period of low volatility suckered many into making the bets that unraveled spectacularly in 2008.

Conceivably, this is a structural reduction in turbulence. But it seems likelier that the period of range-bound and calm trading presages a turn, just as the low volatility of 2007 did. The dollar has been on an upward trajectory ever since the crisis, aided by the intractable political and economic problems of its major trading partner, the euro zone. With a highly polarized U.S. presidential election ahead in 2020, and a calmer political situation in Europe raising hopes that it may at last have hit rock bottom, this period of low volatility may also portend a new long-term trend, this time of dollar weakness.

As one currency strategist puts it: “Even when you throw a ball against a wall, there’s a brief period when it stops.” Foreign exchange markets may be in that brief period right now.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.