Credit Suisse Woes Sink Catastrophe Bonds Tied to Bank’s Risks

Credit Suisse's current troubles sink an obscure catastrophe bond tied to the bank's risks.

(Bloomberg) -- Credit Suisse Group AG peddled a series of unusual bonds in recent years that gave the Swiss firm insurance against the equivalent of a banking earthquake. The owners of those securities are feeling some tremors.

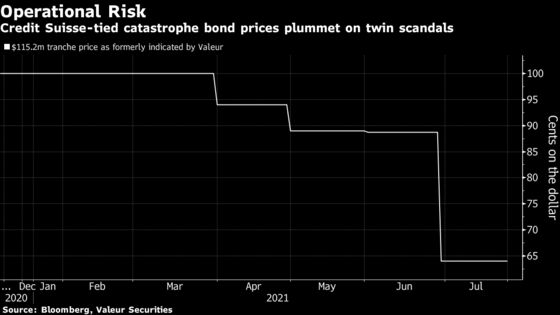

The $461 million of notes, which are rarely traded, were quoted at distressed levels last month, with a sliver of the issue selling at around 60 cents on the dollar. Traders at JPMorgan Chase & Co. recently offered to buy the junior tranche of the notes for around the same price, according to two people familiar with matter who asked not to be identified as the prices aren’t public.

The bond was quoted at par as recently as March, but doubts have grown over whether the bank’s twin scandals tied to the collapses of Archegos Capital Management and Greensill Capital might trigger the insurance and wipe out the principal of the complex securities.

Credit Suisse’s turbulent year is turning into a test case for the unique instruments issued to help reduce the capital the bank had to set aside to cover operational risk, a broad swath of potential dangers from blunders to fraud. The notes, issued in four parts, were modeled on so-called catastrophe bonds that insure against hurricanes and other natural disasters, and features an intricate structure and a prospectus that runs around 400 pages.

The bonds sold in March 2020 -- the third such issuance tied to the bank since their debut in 2016 -- are among the world’s most complex and secretive, requiring investors to sign non-disclosure agreements, according to people familiar with the deal. They tempted investors with large coupons and a risk that was marketed as so small it was practically unthinkable.

“This is probably a textbook case of a catastrophe bond being too complex to price and to market,” Marcos Alvarez, the head of insurance at DBRS Morningstar, said in an interview. “An insurance company would require five or six separate insurance contracts for these perils.”

| How the Bonds Work: |

|---|

Unlike most bonds, this one can’t be described as a debt. It works more like an insurance policy, where the bondholders pay out the insurance if the conditions in the policy are met.

|

Spokespeople at Milliman, Inc., the modeling agent that first helped Credit Suisse design insurance-linked notes, didn’t respond to requests for comments over phone and email. Spokespeople at Credit Suisse and JPMorgan declined to comment. A spokesman at Zurich Insurance Group declined to comment on the notes, citing confidentiality reasons.

Difficult Year

The recent price turmoil has been triggered by confusion over whether Credit Suisse can draw on the insurance for operational failures, imposing heavy losses to bondholders. The notes cover a huge catalog of risks to the bank’s bottom line, making them almost indecipherable even to insurance experts.

People familiar with the terms say that no single operational failure can trigger the bonds.

When the bank pitched the first iteration of the operational risk bonds to clients, a 15-year back-testing showed no operational losses that would have triggered the insurance policy, according to marketing material seen by Bloomberg. It first sold catastrophe bonds in 2016 through Operational RE Ltd. in Bermuda, predicting the annual first loss probability of the insurance policy at around 0.19%.

At the time, it seemed like a win-win for both Credit Suisse and bondholders: the bank benefits from a reduction in its risk weighted assets as well as the insurance, while investors got healthy yields.

But 2021 hasn’t been a typical year for the Swiss lender. The bank, which saw second-quarter profit slump, lost around $5.5 billion to Archegos’s implosion, far more than others that traded with the family office. It’s currently in the process of liquidating supply-chain funds that invested in notes originated by Greensill Capital.

“The market started to consider if these two events may trigger the operational insurance policy, and as a result the note became even more illiquid and scarcely traded,” said Alessandro Noceti, director at Valeur Securities, a brokerage that, until recently, provided quotes on the bonds. “Prices therefore dropped and the bid-offer widened mostly affected by the uncertainty of how the note will be treated in such conditions.”

The two potential outcomes are that bondholders could either see part or all of their principal wiped out if the policy is triggered, or get back their entire investment if it’s not.

| Food for Thought |

|---|

|

Just Like Junk

The latest quarterly interest payment on the $122 million junior tranche was set at 5.64% in the beginning of July. At the time, this was almost equal to the average yield on U.S. triple C-rated corporate bonds, the junkiest of junk bonds, based on data compiled by Bloomberg. Even a safer slice pays 390 basis points above three-month Libor, or 4.04% at the latest coupon reset.

Some investors had shunned Credit Suisse’s cat bonds in 2016 because they couldn’t calculate the risks involved, Bloomberg News reported at the time. They’re still hard to calculate, and only a handful of institutional investors take the time to analyze and invest in the complex catastrophe bonds.

Baillie Gifford & Co. is one of them. The Edinburgh-based money manager confirmed to Bloomberg News that it holds some of the operational risk notes, but declined to comment further. The asset manager also held the World Bank’s ill-fated pandemic bonds. The scarcity of players in the market means that investors who want to exit will struggle to find buyers, and that drags down prices even further.

“There are only a few institutional investors in the market and when you buy, you are typically willing to hold to maturity,” said DBRS Morningstar’s Alvarez. “If you want to exit, you’re going to have a hard time.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.