The Never-Ending Turnaround of Credit Suisse

By simply surviving as chief of Credit Suisse Group AG, the Ivory Coast-born engineer has done what most bankers couldn’t.

(Bloomberg) -- Tidjane Thiam is still standing.

By simply surviving as chief of Credit Suisse Group AG, the Ivory Coast-born trained engineer has done what more experienced bankers couldn’t in trying to fix Europe’s troubled banks. With a restructuring plan he masterminded coming to an end this month, Thiam’s next feat will be to prove to skeptics that a one-time consultant can do more than just cut costs.

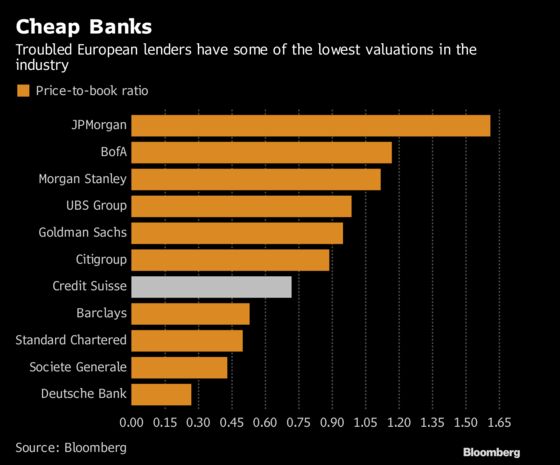

Even after Thiam spent three years weaning the Swiss bank off its obsession with Wall Street and remaking it into a go-to lender for the super rich, investors still aren’t buying what he’s selling. Among 39 European bank stocks tracked by Bloomberg, Credit Suisse was second from the bottom this quarter.

He’ll spend an annual investor day on Dec. 12 trying to change their minds.

“It’s been a relentless restructuring, but what I want to see now from Thiam is that he can grow the bank and generate new business," said Javier Lodeiro, an analyst at Zuercher Kantonalbank in Zurich, who recommends buying Credit Suisse shares.

Since taking the leap from British insurer Prudential Plc in mid-2015, Thiam’s objective has been as clear as it has been fierce: demolish Credit Suisse’s reliance on investment banking and build an institution dedicated to serving the needs of billionaires.

Thiam was willing to be audacious, even flirting with selling a stake in the flagship Swiss unit to replenish capital.

Conversations with more than a dozen current and former employees, executives and board members revealed that it didn’t take long for him to alter the lender’s DNA, especially considering it had spent two decades clambering for Wall Street domination. Instead of being rewarded for taking risks, bankers said they were now expected to avoid them.

Being a newcomer to banking taking over a 162-year-old lender—not to mention the first black man to ever lead a European bank—Thiam needed allies to execute his vision. He quickly nominated six members to the board, including fellow outsider, Pierre-Olivier Bouee, a long-time colleague who followed him from Prudential and led the way in axing key businesses, like distressed bonds and derivatives trading.

That may have saved Thiam from the fate of John Cryan, who took over troubled Deutsche Bank around the same time in 2015, only to be fired in April this year for failing to move fast enough. Antony Jenkins also had a short-lived stint at Barclays Plc: he was sacked in 2015 partly because he wanted to prune the investment bank more aggressively than some board members.

Thiam made certain Chairman Urs Rohner had his back before taking a job that was sure to make him some enemies. They met 19 times before Thiam said yes, according to one person, and Rohner gave his word he’d let Thiam fix a core problem: compared with peers, Credit Suisse’s capital cushion against unexpected losses was too small.

In almost every way, Thiam was the antithesis of his predecessor Brady Dougan, a product of Wall Street trading floors who rejected a state bailout during the 2008 financial crisis, opting instead to rely on Qatari and Saudi investors to fill the gaps. People said Thiam viewed that as a big mistake. He’s been critical of how long the lender clung to an investment-banking led strategy, arguing it put Credit Suisse at a disadvantage to bigger Swiss rival UBS AG and precipitated the stock’s collapse.

Investors cheered when they heard the man who’d worked wonders at Prudential in London was bound for Zurich. By the time he joined, increased regulation and volatile markets had battered the trading business, which contributed 42 percent to adjusted profit before Thiam’s restructuring sidelined the business and knocked the ratio to about 15 percent as of September.

But after an initial bump, the stock has tumbled over 50 percent, partly because the unit was still bleeding money.

“They aren’t in a great position right now and obviously you don’t like to see that as a shareholder,” said Thomas Braun, a money manager at BWM AG in Switzerland, which holds 4.1 million Credit Suisse shares. “But look, if they had stuck with the investment-banking focus things would’ve been more ugly today.”

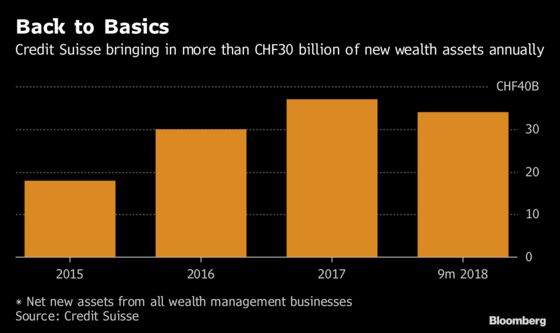

In three years, Thiam has slashed more than 10,000 full-time and contracting jobs, mostly hitting New York and London trading desks. As profits from wealth management grew 62 percent between 2015 and 2017, those from the main trading division sank 40 percent.

While people said Thiam and Rohner sometimes disagreed on strategy, getting the chairman onside was a wise move for the 56-year-old Thiam, especially as tensions flared with bankers who didn’t like him meddling on their turf. Suddenly, wealth managers were getting the bigger salary increases, while equity and debt traders were ordered to keep costs down.

“The board and I personally unanimously agree that Tidjane Thiam is the right CEO to achieve the ambitious growth targets for the coming years,” Rohner said in a statement.

Thiam, who spent his early career working as a consultant for McKinsey & Co., split wealth management into three divisions, including one that later encompassed seven separately managed regions, a stark contrast to UBS’s shift to greater centralization. Credit Suisse investment bankers would from now on serve wealth management clients, especially in Asia where they often go to client pitches with private bankers.

The new regime didn’t sit well with everyone. The overhaul has been confusing and taken a toll on morale, according to eight current and former employees. One banker counted having eight team leaders in two years because they got fired or quit. Staff became paranoid about making mistakes and competition between newly created divisions has grown, others said.

Raised in Morocco and educated at elite French schools, Thiam likes to do his homework. He reads every investor presentation of his biggest rivals, according to one person. But day to day, five people said Thiam rarely engages with employees in Zurich, a contrast to Dougan, who took the tram to work and was more approachable.

People close to him said it isn’t always easy being Switzerland’s first black CEO just as attitudes toward foreigners soured with the rise of the anti-immigration Swiss People’s Party.

Thiam, who recently denied speculation he was quitting finance to run for the Ivory Coast presidency, has thrived in the spotlight. At Prudential, he became the first black CEO in the FTSE 100. Swiss newspaper Blick dubbed him the “Obama of Credit Suisse” shortly before he joined, underscoring the anticipation he could return the bank to glory.

Investors are waiting for him to deliver.

“He took a very sleepy British life insurance company and turned it into a growth stock. He hasn’t worked his magic on this thing yet,” said Marc Halperin, a senior money manager at Federated Global Investment Management in New York, who isn’t ready to offload his Credit Suisse shares after they tanked 35 percent this year.

Within months of joining, Thiam suggested he might sell a stake in Swiss Universal Bank to the public. He didn’t intend to go through with it, according to a person with direct knowledge of his thinking, but wanted everyone to know he’d stop at nothing, even giving up control of a crown jewel, to raise capital.

The maneuver worked. By the time Thiam scrapped the IPO in April 2017, investors were enamored enough to buy 4 billion francs ($4 billion) of new shares. In total, he’s boosted capital by 10 billion francs since 2015, but at the cost of massively diluting each share.

That’s why shareholders have staged regular revolts over Thiam’s pay, the equivalent of $9.7 million last year. A $5.3 billion U.S. settlement over the past sale of toxic mortgage securities and the trading unit’s unexpected losses as recently as the third quarter have worsened sentiment. Thiam may need to announce a share buyback and further downsizing of the trading business on investor day to win back trust.

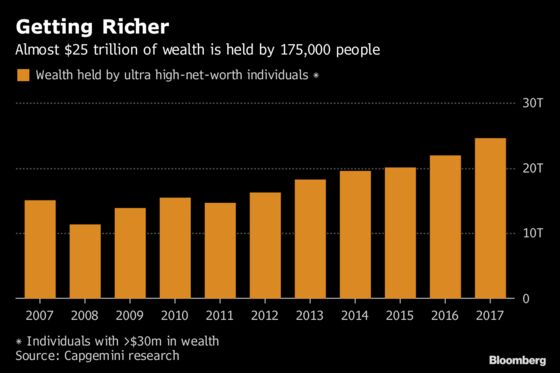

But Thiam’s pivot to private banking, especially in Asia, was prescient. There are now more billionaires in Asia than the U.S., and Credit Suisse is wooing entrepreneurs looking for one place to manage their personal wealth and help their businesses do deals, like IPOs or acquisitions. Asian billionaires can now even borrow against illiquid assets like buildings, roads or plantations.

Some people interviewed suspect international wealth management head Iqbal Khan will take over when Thiam steps down, but they said that’s at least two years away. After all, Thiam has only kept things from deteriorating rather than jump-starting an authentic turnaround. Pretax income is barely back to 2014 levels yet, following three years in the red.

After getting Credit Suisse off life support, the onus now for the six-foot-four banking outsider is to prove his formula can bring genuine healing when tumbling markets are clobbering wealth managers everywhere. If analysts are right, profit growth is on the way.

“The single most important thing in life is not to die,” Thiam said in an interview with Bloomberg Markets in 2016. “First, you stay alive. Then you can think about the future.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dale Crofts at dcrofts@bloomberg.net, Daliah MerzabanJames Hertling

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.