Credit-Fund Industry Staggers in Brazil From Record Withdrawals

Credit-Fund Industry Staggers in Brazil From Record Withdrawals

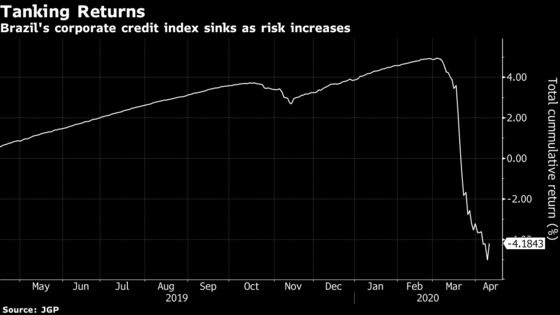

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil’s credit-fund industry is reeling from record withdrawals that are forcing bond sales into a market with few buyers, distorting prices and corporate borrowing costs.

Investors piling into cash in response to the coronavirus crisis took 9.6 billion reais ($1.86 billion) out of such funds in March, on top of 1.5 billion reais in February, according to estimates by JGP Asset Management. The withdrawals amount to about 12% of the independent credit-fund industry’s total outstanding assets.

Measures announced by the government so far, including the possibility of the central bank buying corporate bonds, haven’t been enough to ease the resulting price “dysfunction,” said Jean-Pierre Cote Gil, a portfolio manager and head of credit at Julius Baer Group’s family office in Brazil. The fund industry has calculated that the central bank needs to buy about 20 billion reais of bonds directly, in a market that totals 250 billion reais, to bring liquidity and borrowing costs back to normal, Cote Gil said.

The monetary authority hasn’t said how much it plans to buy or which type of bonds, and purchases need Senate approval.

“The market still has many doubts about how it will be executed in Brazil,” Cote Gil said.

Corporate credit funds were among the fastest-growing investments for Brazilians in recent years, offering relatively high yields as benchmark interest rates fell to record lows. Total assets under management by independent managers in the segment increased to almost 100 billion reais last June from about 15 billion reais in 2014, according to JGP. They fell to about 90 billion reais at the beginning of this year.

To attract Brazilians demanding daily liquidity, about half the credit funds promise investors they can withdraw their money on the day of a redemption request or one or two days later.

That promise has turned the funds into a hard-to-resist source of immediate cash for individuals and institutional clients grappling with fallout from the coronavirus crisis. Withdrawals provided liquidity to navigate the lockdown period and comply with margin calls, debt payments and reduced wages or revenue.

In just one example, assets at the Iridium Apollo FI RF CP Lp fund, which allows withdrawals one day after the request, plunged 43% to 1.45 billion reais from Jan. 23 to April 7, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. It’s returned negative 4.8% in the past month.

Competition with equity funds is also weighing on corporate credit funds, which had already lost about 10 billion reais in total assets in the last quarter of 2019 as falling interest rates and narrowing corporate credit spreads cut returns. As stocks prices tumbled in recent weeks, investors saw opportunities to move into equity funds, which had net inflows of 8.5 billion reais in March, according to Anbima, the capital-markets association.

Forced selling by credit funds pushed secondary-market trading in the local bond market to a record 20 billion reais in March, almost doubling the monthly average of 12 billion reais. Buyers are almost entirely banks, Cote Gil said.

Itau Unibanco Holding SA, Latin America’s biggest bank by market value, said April 6 that it had purchased 2 billion reais in assets from institutional clients since the beginning of March.

“Most funds were forced to sell top companies’ bonds that were in their portfolios, because they have more liquidity, bringing borrowing costs for those companies to a dysfunctionally high level,” Cote Gil said, adding that the dynamic has affected the entire “credit chain,” including small and midsize companies.

“Why would banks or other investors lend money to a company and get lower interest interest rates if they can buy triple-A corporate bonds on the secondary market that pay much more?” he said.

Rising Rates

Before the coronavirus crisis, a triple-A credit in Brazil would pay the interbank rate DI plus 1% or 1.5% to borrow for three to four years, depending on the sector, Cote Gil said. Banco Bradesco SA paid as little as DI plus 0.3% at one point. Bonds for those companies now trade at DI plus 4% or 5%, with almost no differentiation by credit risk.

The crisis is a setback for a local bond market that had been fighting to shed its reputation for a lack of transparency. Before the rise of credit funds, the majority of local bonds were traditionally purchased by banks, which held them on their balance sheets to maturity. They were a kind of bank loan in disguise, booked as bonds as a way lenders could avoid paying taxes.

As credit funds got bigger, the share of such loans had dropped to about a third of the overall primary market. Since the pandemic, however, the practice has increased again with a vengeance: All the new bonds issued in March or April were sold to the banks, according to industry executives.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.