Covid-Era Tech Grads Launch Careers From Parents’ Homes

Some students who had gotten job offers from companies like Uber had them rescinded or lost their jobs soon after starting.

(Bloomberg) -- Eric Lee has dreamed of working for Microsoft Corp. for as long as he can remember, and was stoked this spring to land a job at the tech giant right out of college. But instead of traveling across the country to start his career at Microsoft headquarters in Redmond, Wash., Lee joined the workforce this month from his family’s house in the suburbs of Boston.

The arrangement has its comforts. Every hour Lee’s mom brings him a different type of cut-up fruit, then usually noodles for lunch. But he feels disconnected from his new colleagues in a way he wouldn’t if they were sharing an office. When Lee gets stuck on a tricky line of code, he sends a message asking for advice, then tries to figure it out himself. If that fails, he passes the time until he gets a response by watching videos on TikTok. Sometimes it takes hours. “I’m afraid of asking dumb questions or intruding when they are AFK, away from keyboard,” Lee says. “So I just wait.”

The feeling of being forced to wait is common for students who graduated college this year. Until March, things were moving fast for them. Most were born around 1998, too young to have memories of the dot-com bust or anything but the vaguest recollections of the 2008 financial crash. They’ve spent their entire lives plugged into smartphones, and many have seen a career in tech—rather than in medicine or law—as the highest marker of success. And tech had been booming.

But the economy was slowing even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit the U.S., and the last five months have been devastating. The upheaval can be seen in industries such as technology, and the approximately 200 students who graduated this spring from the computer science program at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign, one of the top 10 engineering schools in the country. Lee is one of its so-called Class of Covid, those students who finished their studies just as the pandemic was gripping the country.

Graduates from the program’s 2019 class earned an average starting salary of $108,000. Over 97% of graduates reported having full-time work or enrolling in graduate school within six months, according to the school. The pandemic had an immediate impact on this year’s graduates. Some students who had gotten job offers from companies like Uber Technologies Inc. and International Business Machines Corp. had them rescinded or lost their jobs soon after starting. Others were told their start dates were being delayed by months. Those who have gotten jobs, like Lee, begin their careers in a weird state of limbo.

These travails are mild compared to the havoc that Covid-19 has wreaked on less advantaged workers. The tech industry was the best-performing sector of the economy before the pandemic, and large tech companies are not facing the existential threats of, say, airlines or retail chains. Computer science graduates, some of the most sought-after workers in the country, will be better off than those in other fields. But the Class of Covid graduates are likely to have a harder time than students who graduated just one or two years earlier, and their personal experiences provide a window into the post-pandemic economy.

Tell us about your experience: If you graduated this year email us your story about how you’ve been impacted by the pandemic’s impact on the economy.

Graduation day at UIUC felt hollow. The university cancelled its in-person commencement ceremony, and administrators rushed to cobble together a virtual replacement. Lee slept through it. Caren Zeng, who lives near San Francisco, tried to make the most of the situation. She ordered a cap and gown and posed for photos in her backyard, the California redwoods in the background a reminder that she wasn’t actually in Illinois. Her family crammed into the living room to watch the 30-minute prerecorded event. Zeng’s name flashed across the screen for a few seconds. “It just didn’t ring true at all,” she says. “I feel like the moment was kind of robbed from us and there’s no real replacement for it.” This week, she’s starting a job at Alphabet Inc.’s Google. Technically the job is located at the company’s New York office, not its headquarters in nearby Mountain View. But the distinction doesn’t much matter for now, since Zeng is doing it from home.

Surabhi Sonali, like Lee, started a career at Microsoft from her parents’ home this month. Sonali spent her first morning on the job rearranging her bedroom furniture so its bright pink walls and teddy bears wouldn’t show up in the background of her video calls. “I want to set up my laptop so people see the least amount of the girly decor all around my room,” she says. Sonali has less control over the sounds of her brother and sister playing Xbox in the bedroom next door.

While Sonali is saving money on rent, avoiding daily commutes and sometimes working in pajamas, any novelty has already worn thin. She interned at Microsoft three times before getting hired, and remembers how much easier it was when she could just walk up to someone’s desk to ask a question. “It’s 100% weird to start a full-time job at my parent’s house,” Sonali says. “This is the most anti-climactic life transition ever.”

Working from home can be a trying experience for people at all stages of their careers, but the challenges for new graduates are unique, says Joseph Altonji, a professor of economics at Yale University. It is harder to cultivate mentors through a screen than at lunches and happy hours. “This is different for people just entering the workforce who don't have a lot of prior experience,” says Altonji. “They've literally never set foot in the company office building and not met their boss in person, not met their coworkers in person.”

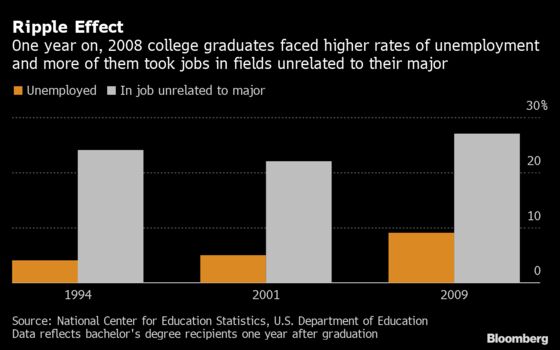

The impacts may be long-lasting. Altonji co-authored a study that found that workers graduating during the 2008 financial crisis had earnings as much as 10% lower in their first year working than they would have otherwise. The initial setbacks were often permanent. He expects to see a similar dynamic with this year’s graduates. It will take longer for many people to find work. The weak labor market will cause some people to take jobs that are less relevant to their academic backgrounds. Once employed, new graduates who begin work remotely are likely to take more time picking up both technical and soft skills, says Altonji.

A Microsoft spokesperson said the company is aware that bringing young employees into the workforce remotely isn’t ideal. It is working on various ways to improve the experiences of working from home, like giving managers specific training on how to manage remote workers, and how to aid employees in times of crisis.

UIUC’s administration has also been contemplating whether it needs to take a more active role supporting its graduates, says Nancy Amato, head of its computer science department. Because most graduates have thrived professionally, she says, alumni services in the past have consisted of checking in to keep track of where they ended up. “We don’t really offer to support them,” says Amato. “And I think we need to, because right now they’re kind of in between.”

Some UIUC grads are still searching for jobs. Alan Jin grew up in Wenzhou, China, and moved to New York with his family when he was in high school because his parents thought it would increase his chances of getting into a top engineering college. Jin fell in love with virtual reality and computer vision. “I thought, if I just studied CS and went to a good school, I’d easily be able to find a job making a lot of money,” he says.

After applying to a few dozen companies during the school year, Jin landed an internship at a high frequency trading firm in Chicago that he hoped would turn into a full-time job. Jin is crashing at his aunt and uncle’s house, where the Wi-Fi isn’t the best. Online team-building events don’t seem like effective ways to build relationships that could increase his chance of landing a permanent position. At one recent virtual event, Jin and other employees tie-dyed t-shirts while chatting on Zoom. “It’s cool, I guess, but I don’t think I’ll wear it,” Jin says, holding up the shirt he made. “Mostly, I work a lot and don’t talk to anyone. It still feels kind of weird.”

Jin has become pessimistic enough about his chances at his current firm that he’s begun applying for jobs again. He hopes to land a job with a prominent California tech company. “No one seems to be hiring,” he says, lamenting his bad timing. “If only I had graduated earlier.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.