The Low-Debt Era for Eastern Europe May Be Ending on Covid and 2008 Fallout

The Low-Debt Era for Eastern Europe May Be Ending on Covid and 2008 Fallout

(Bloomberg) -- There’s a shift taking place in the low-debt economies that joined the European Union after the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

An aversion to borrowing that once characterized much of the bloc’s ex-communist contingent is being jettisoned following the 2008 global crash and the Covid-19 pandemic in little over a decade. Much of the region, which has led the continent’s economic growth for years and counts five euro-area members among its ranks, is now set to endure higher indebtedness for some time.

“If we’re facing a once-in-50-years shock, we should be repaying these debts over 50 years,” said Beata Javorcik, chief economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development -- established in 1991 to smooth the post-Soviet transition. “We’ve learned after the financial crisis that premature austerity will backfire.”

While many countries have set aside debt concerns to boost coronavirus-relief efforts, the shift in eastern Europe, where borrowing has traditionally been something of a taboo, carries more significance.

Austerity imposed by Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu in the 1980s to repay foreign loans brought food shortages and power blackouts that eventually triggered the revolution in which he was executed. Russia defaulted on its sovereign debt in 1998, causing widespread misery. Polish borrowing has been updated in real time on a digital display in Warsaw since 2010.

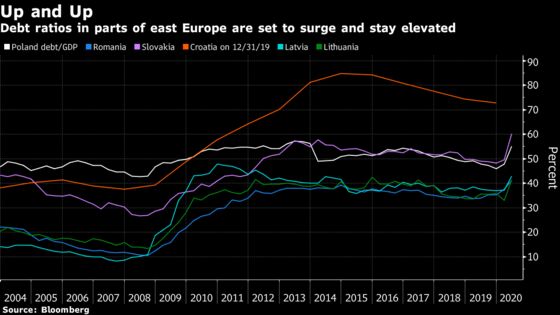

Caution has kept borrowing far below that of western Europe, helping bond yields tumble and credit ratings rise. The region’s worst recessions in three decades is prompting a change of tack, however.

Take Romania. The government went into the 2008 global financial crisis with a ratio of debt to gross domestic product of about 12%. That more than tripled in the subsequent years and didn’t drop substantially before Covid-19 struck. It’s set to hit 55% by the end of 2021, and with anti-crisis measures including permanent spending items like higher pensions, paring it back will be hard. Its investment-grade credit rating is in jeopardy.

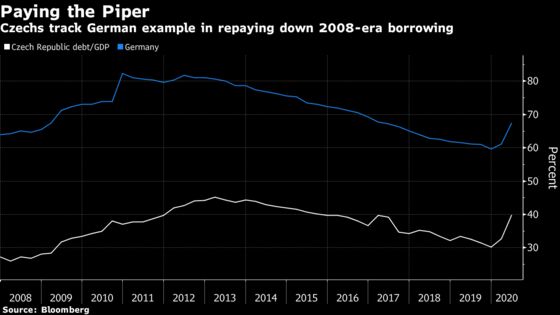

The trend won’t play out everywhere. Tracking Germany, the Czech Republic repaid much of what it borrowed in the aftermath of 2008 and may try to do so again. Hungary’s debt has long been elevated.

But Poland is poised to breach a 60% constitutional limit on government debt, while Croatia’s ratio has more than doubled since 2008 and will approach 90% next year. Even in Estonia, which has long had Europe’s lowest debt load at less than 10%, borrowing is set to more than triple by 2024.

Ardo Hansson, the Baltic country’s ex-central bank chief, channeled familiar anxieties as he called fiscal-consolidation plans in the coming years too weak.

The government may “dig a hole that will be too deep to climb out of, thereby paving the way for a steady increase in public debt,” Hansson, who sat on the European Central Bank’s Governing Council, wrote in an opinion piece.

Some officials say that won’t happen on their watch.

“In the long run, fiscal easing shouldn’t pose problems for debt-servicing as long as the boom returns,” said Grazyna Ancyparowicz, a Polish central banker.

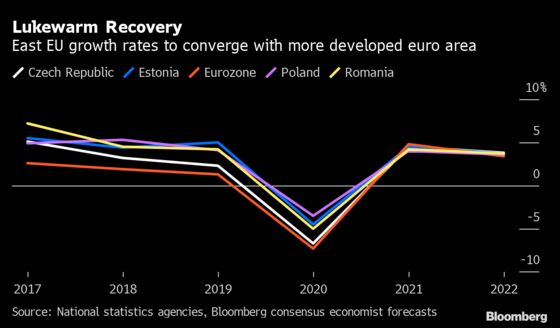

But eastern European growth rates during the next two years are looking more like the slower pace typical in the more-developed euro area.

For Mihai Purcarea, who helps manage the equivalent of $1 billion of European debt and equity investments as chief executive officer of BRD Asset Management in Bucharest, that will make it trickier for the region to repay new borrowing.

“We have a fast increase in debt levels while real GDP and inflation seem more difficult to put on an upward trend, at least in the medium term,” he said. “The current developments of Covid-19 and the lockdowns imposed by many countries are likely to lead to further debt increase and lower future GDP paths.”

Slower expansion could weigh on social spending that’s jumped in Poland and Romania. Polish debt will stabilize at just under 60% in the medium term, according to the International Monetary Fund, which said last week that “better targeting of social benefits,” among other measures, would eventually contribute to fiscal consolidation.

“We’re facing a new paradigm,” said the EBRD’s Javorcik. “Debt levels will remain higher for the foreseeable future.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.