Airline Passengers Behaving Badly Rarely Face U.S. Prosecution

Airline Passengers Behaving Badly Rarely Face U.S. Prosecution

(Bloomberg) -- The passenger on the Alaska Airlines flight repeatedly dialed 911 before it even left the gate in Seattle. He claimed the plane was being hijacked. Then he called the FBI to say there was a bomb.

Police stormed the plane and evacuated everyone before discovering it was a hoax. The false report delayed the Jan. 23 flight for hours, forced the rescreening of baggage and may have broken a federal law that could land the passenger in prison for five years.

But, so far, no charges have been filed.

That may be because misconduct on airliners -- which in the past year includes everything from passengers who refuse to wear face masks to others who assault flight attendants -- is governed by a patchwork of federal, state and local agencies that aren’t always well equipped to prosecute such cases.

“It is a problem,” said Loretta Alkalay, the former FAA eastern regional counsel and an adjunct professor at Vaughn College of Aeronautics & Technology. “The state police usually don’t have jurisdiction. Once it’s in flight, that’s the fed’s jurisdiction and the U.S. attorneys are overwhelmed by more serious cases.”

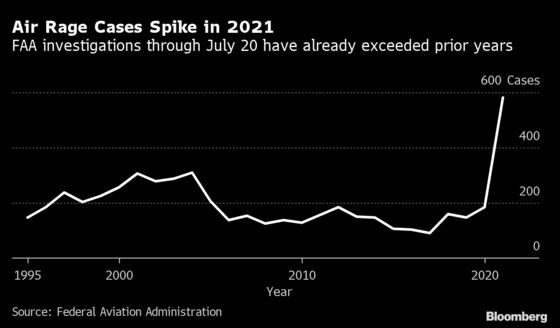

More than 3,500 reports of unruly passengers on flights have been logged this year by the Federal Aviation Administration, far exceeding anything the agency has seen in the past. Of those, 581 were deemed serious enough to prompt a formal investigation, the FAA said.

But the agency -- which has a primary mission of ensuring air safety, not security -- has no authority to bring criminal charges. Since December it has announced 46 civil penalty cases.

The government is straining to keep up.

The Seattle case, for example, is being handled by the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, which declined to bring felony threat charges because there was no actual hijacking and his comments about a bomb didn’t constitute an actual “threat,” spokesman Casey McNerthney said. Prosecutors are considering whether to charge the man with false reporting, but it’s only a misdemeanor under state law.

Federal law makes it a serious crime to falsely report a hijacking. But the U.S. Attorney’s office in Seattle hasn’t brought charges and it doesn’t appear the case was referred to it.

For now, the 32-year-old Oregon man faces a possible fine of $10,500 from the FAA. Such fines are subject to challenge and negotiation.

A Bloomberg News review of FAA cases, court records and news reports found several instances of serious cases in which passengers allegedly struck flight crew members or engaged in other criminal acts but no charges were filed.

“If it’s a criminal activity, it ought to have criminal prosecution,” Southwest Airlines Co. Chief Executive Officer Gary Kelly said on a conference call Thursday. “There are extreme cases out there that are occurring and I think that we will be for the full enforcement and letter of the law, whatever is available. We would be in support of that.”

FAA Administrator Steve Dickson ordered stricter enforcement after numerous cases of fights and other incidents on planes erupted around the time of the Jan. 6 storming of the U.S. Capitol.

Since then, many incidents have become intertwined with the divisive politics over the Covid-19 pandemic. More than 2,600 unruly passenger reports, or 74% of the total in 2021, have involved the refusal to wear mandatory face masks, according to the agency.

“The system was not designed to deal with air rage incidents because they were always few and far between,” said Jeffrey Price, an airport security consultant and professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver.

It’s a difficult situation for all involved and building a solid case takes time and resources, Alkalay, the former FAA regional counsel, said. Airport police forces may not always provide the proper information FAA lawyers or federal prosecutors need to build cases. Similarly, information from flight crews is often incomplete, she said.

Call to Prosecute

A group of airline associations and industry unions last month urged Attorney General Merrick Garland to “send a strong and consistent message” by more aggressively bringing criminal cases in the worst cases.

“Flight attendants continue to encounter unprecedented levels of air rage and passenger misconduct,” Julie Hedrick, president of the Association of Professional Flight Attendants union at American Airlines Group Inc. said in an emailed statement. “Where criminal charges apply, the federal government should prosecute offenders to the fullest extent.”

In a statement, the Justice Department said prosecutors consider a range of factors before bringing charges. They include the severity of the offense and whether lives were endangered, the impacts on victims and the mental health status of the person who committed the act.

“Interference with flight crew members is a serious crime that deserves the attention of federal law enforcement,” the department said in the statement.

Federal charges were filed in 16 cases in the year ending Oct. 1, 2020, and 20 in the year before.

Bringing more criminal cases might help slow the explosion of cases, but historically it has proven difficult to win convictions on such cases and to get federal prosecutors to devote resources to the issue, said J.E. Murdock, who served as FAA’s chief counsel and acting deputy administrator in the 1980s. One avenue might be a kind of public shaming in which the government releases the names of people involved in such incidents, he said.

A similar idea floated by flight attendant unions is to add the names of those involved in unruly incidents to the government’s no-fly list. Airlines say they’ve added hundreds of people to internal lists this year prohibiting them from buying tickets following incidents on flights, but they don’t share the names with competitors.

Federal legislation to increase penalties and to give local law enforcement more authority over the cases might also help, Alkalay said.

Flight Attendant

There are recent signs of a willingness to prosecute. A dozen people have been charged with interfering with a flight crew this year through July 15, according to federal court records.

Among them: an off-duty Delta Air Lines Inc. flight attendant who caused a disturbance on one of his employer’s flights on June 11 and had to be restrained faces federal charges of interfering with a flight crew, which carries a prison term as long as 20 years.

Some additional criminal cases also may be pending. “There are a number of cases where investigations are ongoing and the evidence is still being reviewed for possible charges,” said Emily Langlie, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s office in Seattle.

She declined to comment on specific cases, but one possibility involves a Honolulu-to-Seattle flight that prompted the largest proposed penalty announced by the FAA this year.

A man on the Delta plane had to be restrained in handcuffs after trying to break into the cockpit and striking a flight attendant in the face, the FAA said. He later freed one arm from the restraints and hit the flight attendant again, the agency alleged. The FAA is seeking a fine of $52,500.

Then there is the woman on a JetBlue Airways Corp. flight from Miami to Los Angeles who yelled at a flight attendant and slammed into his body, almost knocking him into a lavatory, according to the FAA. She was removed from the plane after it diverted to Austin, Texas.

The U.S. Attorney’s office in the Western District of Texas doesn’t have a case on the incident, spokeswoman Lora Makowski said in an email. The FAA has proposed a $15,000 fine against the passenger.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.