The Dollar Crunch Is Europe’s Gift to Asia

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Banks in Asia are suddenly shy to part with dollars. And who can blame them? Many of their corporate clients are borrowing the U.S. currency and depositing it with the same banks — just in case they can’t get the funding when they need it.

The caution amid the coronavirus outbreak isn’t all that different from Amazon.com Inc. trying to discourage vendors from cornering toilet paper supplies. “Corporate banks are becoming a bit more discretionary about permitting draws on credit lines where hoarding cash is the sole objective,” according to Greenwich Associates consultant Gaurav Arora.

The dollar squeeze is evident, as one of us wrote Monday, in the hefty premiums South Korean banks must fork out to borrow the U.S. currency — a reliable indicator of trouble in the past. It also appears that China’s banks may be less eager or able than before to fund the dollar needs of their corporate borrowers, Bloomberg Opinion’s Anjani Trivedi noted Wednesday.

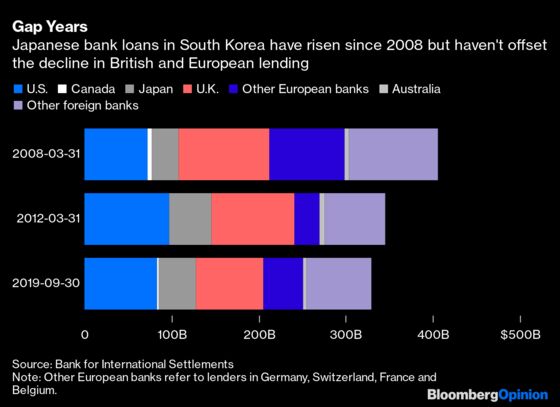

For Asia, the crunch is an unwanted gift from European lenders, whose departure from the region post-2008, as well as regulations that reined in Wall Street firms, have led to a funding hole. Japan’s banks have expanded and lenders like BNP Paribas SA have scaled up trade finance, but they’re yet to fill the void, especially as troubled Deutsche Bank AG shrinks. The German lender was in the top five corporate banks in Asia in 2014; last year, it wasn’t even in the top 10, according to Greenwich.

Some countries like Korea have felt the loss more keenly than others. U.K. banks’ exposure to Korea has dwindled to $77 billion from $104 billion in the first quarter of 2008. German lenders’ claims have fallen to $13 billion from $36 billion.

Japan’s lenders have taken up part of the slack. Driven by negative interest rates and aging demographics at home, they have dished out funds aggressively in Southeast Asia as well as to global deal-chasing clients like SoftBank Group Corp. The large U.S. operations of megabanks like Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc. also provide them with liquidity, as does their stack of fully convertible, cheap yen deposits. But some Japanese lenders have piled into off-balance sheet products, which suck liquidity in times of stress. Japan's Norinchukin Bank, a lender to farmers and fisherman, was one of the world’s largest buyers last year of collateralized loan obligations, bundled U.S. leveraged loans.

When the Fed extended emergency swap lines to South Korea, Australia, Singapore and New Zealand last week to ease the worldwide dollar shortage, a step that our colleague Shuli Ren called for here, it was a sign that the liquidity problem was serious enough. Overall, the Fed gave temporary access to nine authorities in addition to the five that it has permanent arrangements with for making dollars available. Emerging economies like India, Indonesia, Chile and Peru, though, have seen their requests for swap lines rebuffed in the past. The U.S. only helps those it sees as important to the stability of its own banking system.

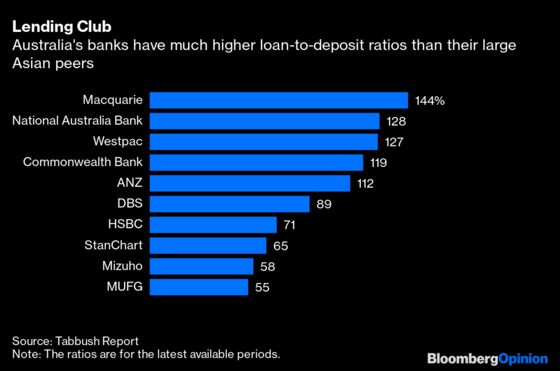

So what can Asia do? Start with the most extreme case. Australia needs U.S. dollar funding not just for foreign-currency loans but also for Australian dollar mortgages. That’s because the domestic deposit base is small, compared with the size of the banking industry. The average loan-to-deposit ratio of Macquarie Bank Ltd. and other major Australian lenders was 126% versus 68% for the top Asian banks, namely DBS Group Holdings Ltd., Mizuho Financial Group Inc., MUFG, Standard Chartered Plc, and HSBC Holdings Plc, according to banking analyst Daniel Tabbush, founder of Tabbush Report.

Offshore funding sustains around one-third of major Australian banks' total worldwide operations. While the International Monetary Fund and others have flagged the reliance on foreigners as problematic, the Australian regulators have so far refrained from discouraging lenders to borrow abroad. Yet, the fact that the country had to seek dollars from the Fed during the epidemic upheaval and auction them to its banks will call into question the sagacity of this relaxed approach.

In rest of Asia, one lesson from the dollar squeeze is to shun protectionism. Well-capitalized regional banks like Singapore’s DBS could supplement the three traditionally entrenched foreign lenders: HSBC, StanChart, and Citigroup Inc., a big cash management bank for Western multinationals. DBS could emerge as an Asian global bank, though in good times its expansion has been stymied by regulators playing to nationalist political sentiment, as we saw when it wasn’t allowed to buy Indonesia’s PT Bank Danamon in 2013.

The next step may be to seek more intermediaries with scale. JPMorgan Chase & Co. is pumping top dollar into serving corporate treasuries as a safeguard against the fickle fortunes of investment banking. Japan’s lenders could also do more: MUFG is already one of the region’s most aggressive lenders and has the historical advantage of having a dollar clearing license, like HSBC.

Unlike 2008, this isn’t a credit contagion yet, though that could change if large, messy financial bankruptcies were to erupt. But beyond the current crisis, the regulators must plan for the next squeeze. Since not everyone can rely on the Fed, the dollar supply chain is each country’s responsibility. At least until a credible alternative to the U.S. currency comes along.

The standing facilities are with the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada, the Swiss National Bank and the European Central Bank.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nisha Gopalan is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and banking. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones as an editor and a reporter.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services. He previously was a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He has also worked for the Straits Times, ET NOW and Bloomberg News.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.