Coffee Supply Isn’t Safe With Latin American Harvest Threats

Abandoned Coffee Farms Mean Supply Shortage Could Get Even Worse

(Bloomberg) -- The coronavirus pandemic has upended life in unprecedented and countless ways. Now it may be coming for your coffee.

Bank closures, reduced working hours, hampered mobility and fears of contagion on farms have all raised serious concerns that there won’t be enough laborers to collect coffee beans for harvests that will soon get underway. The pressure is especially acute in Colombia, Brazil and Peru, which account for almost two thirds of world output for the smooth-tasting arabica beans.

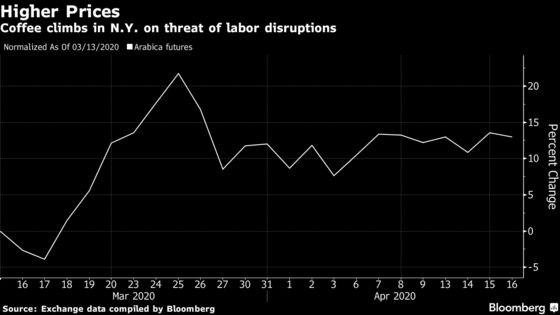

Coffee production was already forecast to fall short of demand this year, with the gap being filled by leftover stockpiles from previous harvests. Now the threat of labor shortages means a small surplus expected for next season could shrink, or get wiped out. Meanwhile, inventories have been depleted at a time when the virus unleashed a wave of grocery store panic buying. Arabica prices have jumped as a result, with futures in New York up about 16% in the past month.

In Peru, beans are grown by farmers from the highlands of Puno, who migrated into the growing areas of the Sandia district. Crop collection is supposed to start next month, but Jimmy Larico, the general manager of cooperative Cecovasa is worried there won’t be enough workers. At the same time, growers themselves are leaving to escape shortages for food and other basic goods in the area.

“Entire families are leaving,” said Larico. “They’re going on foot because of the restrictions” on public transport, he said.

“Many people are abandoning their farms. The harvest is at risk if the quarantine persists.”

Coffee picking is tough work. Farm hands are often in the field from sun up to sun down, painstakingly searching for the beans that are ripe enough to gather, while being delicate enough to not damage the rest. In Brazil, the world’s top arabica grower, much of the harvesting activity has become mechanized, which can shield growers from a dearth of laborers. But in Colombia, the No. 2 producer, a lot of the crop is still gathered by hand.

It’s often a low-paying job, so workers end up in packed living conditions. That increases the risk of the virus spreading if even just one person is infected.

Colombia’s National Federation of Coffee Growers, known as Fedecafe, is working with the government to develop protocols that could help prevent workers from getting sick. The group is also creating a job bank to make sure there’s enough labor and hopes to lure some of the unemployed people in other sectors, said Roberto Velez, the federation’s chief executive officer. Still, he acknowledges that the pandemic has already caused some slowdowns.

Suppliers and intermediaries in Colombia have had problems accessing producing regions under lockdown restrictions. They’ve had trouble collecting coffee supply, while reduced banking hours also make payment operations more restricted, according to Geneva-based trader Sucafina SA.

“This is an issue more about legislation and what governments do to ensure workers can move,” said Christian Wolthers, president of Wolthers Douque, an importer in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, which deals with suppliers in South and Central America. “They will do anything possible to keep the commodity flowing. They are not going to let a national product wither on the trees.”

For consumers, some of the gains in coffee prices could start to ease as panic buying at grocery stores dies down. At the same time, the closure of restaurants and cafes across the globe could also slow overall demand growth, even as people keep brewing pots at home.

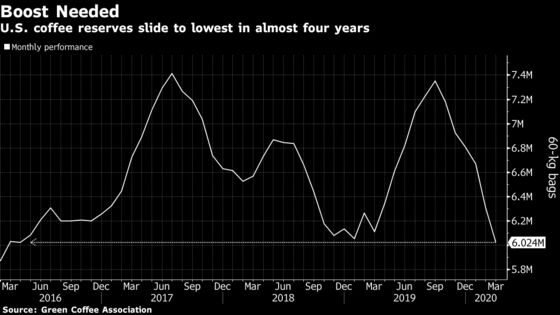

But for now, inventories are tight. U.S. stockpiles of unroasted beans fell for a sixth straight month in March to the lowest since April 2016, data from the Green Coffee Association show.

And if consumption does end up dropping because of the restaurant closures, that’s going to leave growing cooperatives like Peru’s Cecovasa in a very tough spot, facing both the labor crunch and uncertain demand.

“Coffee growing is facing serious problems,” said Larico. “That’s why we’re asking the government for agricultural aid -- to be able to survive somehow.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.