Clorox Bets Big on Not Going Back to Normal

Clorox Bets Big on Not Going Back to Normal

(Bloomberg) -- Linda Rendle, the CEO of Clorox, knows what the doubters are saying.

That the pandemic moment is fading. That the frenetic sales gains are over. That Clorox’s stock will languish again.

Rendle is convinced they’re all wrong. At just 43, the newly minted CEO is the company's youngest ever leader—and first woman in the role—but she has been at the consumer products giant for almost two decades. And when she looks at all the scrubbing and wiping (and worrying) of the past year, she doesn’t see habits that will disappear along with the pandemic.

“This behavior is sticky,” Rendle said.

Her conviction can be seen in an Atlanta suburb, where last week Clorox opened a second production line at a factory that boosted the number of wipes canisters it can ship to 1.5 million each day. To keep that facility busy as Covid-19 recedes, Rendle is increasing the company’s marketing budget by 30% and is using the Clorox brand’s sudden high-profile to push into new places, including partnerships with the NBA and Uber.

“We want to do everything we can to keep these people as part of our franchise,” Rendle said. “And continue to bring new people in.”

It’s a pivotal moment for a company that had its fortunes lifted overnight by the pandemic—joining the likes of Zoom and Instacart. Clorox’s portfolio, a lineup that spans pool cleaners to pet odor eaters, took off as Americans stayed home and disinfected their lives. Revenue, which had been eking out low single-digit gains, jumped 23% to $7.5 billion in 2020.

Wipes were at the center of the boom. The U.S. category leader with about a 50% market share (Reckitt Benckiser’s Lysol is a distant second) sold out in weeks. Rendle, a mother of two, said that even she struggled to keep her home stocked.

Soon wipes became part of the national conversation, with entire websites dedicated to where to find them. Canadian musical duo Chromeo even seized on the popularity and released “Clorox Wipe” with lyrics like: “If I could reincarnate tonight, I would be your Clorox wipe.” (The video has eight million YouTube views.) By August, Rendle went on Good Morning America to reassure host Robin Roberts and the country that more canisters were on the way.

“The category went from zero to 60 in seconds,” said Chris Carey, an analyst for Wells Fargo who said wipes account for roughly 10% of the company’s sales and are a top five product line along with Kingsford Charcoal and Glad trash bags. “Companies aren’t set up to handle that.”

By the end of 2020, a year in which the stock surged the most in more than two decades, Clorox had caught up to demand. But investors appear to be discounting the company’s ability to maintain a sizable portion of the Covid boom. And Clorox is not alone; consumer product makers and retailers on the right side of the pandemic are all having to prove that they can hold onto these gains.

In February, Clorox forecast sales would be about flat over the next two quarters (tough comparisons from the height of the pandemic played a major role), and the stock tumbled—it’s now down 20% since a record high in August.

“People won’t be disinfecting as much once we get past the pandemic—it will be a slow retreat,” said Linda Bolton Weiser, an analyst for DA Davidson who last week downgraded Clorox shares to the equivalent of a hold. But she said there is a bull case where Clorox retains more of these new customers than expected.

Rendle points to internal research showing that more than 90% of people say they won’t revert back to their pre-Covid cleaning and disinfecting routines. She’s one of them.

“I can’t wait to go into a restaurant again—I cannot wait,” Rendle said during a video call from her home in the San Francisco Bay Area. But when she does, she’ll be thinking: “Are these people here healthy? Have surfaces been cleaned?”

If anyone has a handle on Clorox’s potential, Rendle fits the part. She joined Clorox in 2003 as a sales analyst, just a few years after graduating from Harvard University, where she earned an economics degree and lettered in volleyball. From there, she methodically worked her way up the nearly 9,000-employee company with 13 titles in 17 years. By May, she had climbed to president as the heir apparent and four months later became CEO, replacing Benno Dorer, another longtime Clorox veteran who’d been in the top job for almost six years.

When Covid hit the U.S. a year ago, 70 days of inventory in wipes disappeared in two weeks. For months, Clorox struggled to fill those empty shelves. Then it started work on adding a production line to its factory about 10 miles south of Atlanta in Forest Park, Georgia.

Inside the 258,000-square-foot complex, you can sense the company’s urgency. Giant rolls of nonwovens—the square sheets that consumers call wipes—are coiled on a spool and cut into sheets. Speedy conveyor belts run them through a canning machine. A robotic arm organizes the finished products before they are placed on pallets taller than any of the factory’s 200 workers. At full capacity, 500,000 units can be produced in eight hours.

“It’s been a really fast-tracked project,” said Rick McDonald, Clorox’s chief supply chain officer.

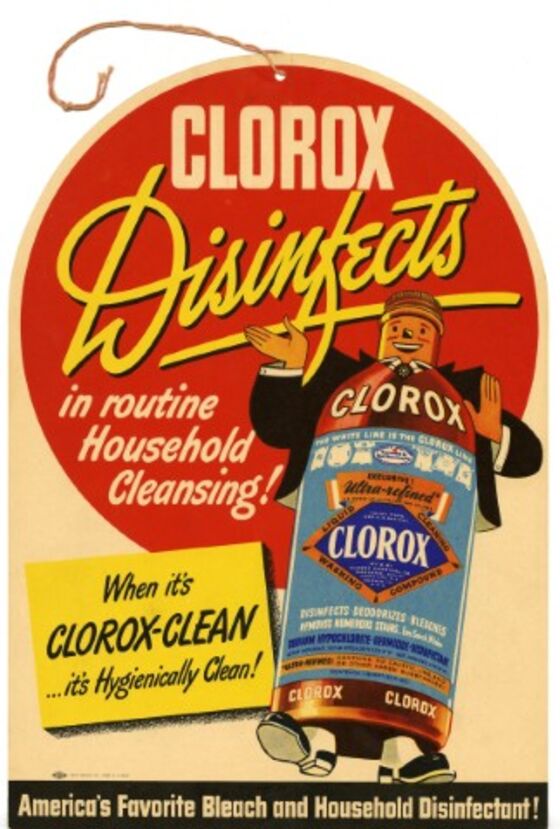

Nimbleness has rarely been associated with packaged goods companies like Clorox, but its initial breakthrough came from a big pivot early on. The company was founded in 1913 in Oakland—where it’s still headquartered—when five men each put in $100 to build America’s first liquid bleach factory. Within a few years, an early investor led the company, and it was his wife, Annie Murray, who pitched the idea to dilute industrial strength bleach for home use. She was ahead of her time, building demand with free samples at her nearby grocery store.

From there, Clorox was a one-product company for more than half a century. Procter & Gamble acquired it in 1957, only to divest it about a decade later after losing an antitrust case at the U.S. Supreme Court. Independent again, it ignited growth by creating in-house brands, like Soft Scrub, and acquired others, including turning the masses onto Hidden Valley ranch salad dressing after a deal in 1972.

Marketing has always been core to Clorox’s success. Early on, it used a giant billboard to pitch Bay Area ferry riders and plastered its logo on cargo ships. Throughout its history, the message has largely been about making housework easier—early ads touted how “Clorox saves the day!” for women. A commercial shortly before the pandemic explained how one wipe can clean 50 feet of counter space.

But now Clorox is using weightier messaging such as the trademarked: “When it counts, trust Clorox.” One spot shows a mother and daughter cleaning with Clorox products before grandpa’s visit.

The company is also inking more corporate deals. It has a multi-year agreement to be the official cleaning partner of the NBA and WNBA sports leagues. Earlier this month, it started the Clorox Safer Today Alliance, a partnership with the Cleveland Clinic and CDC Foundation, that it describes as helping businesses “create healthier public spaces.”

As part of the initiative, Uber, United Airlines, Enterprise Rent-A-Car and AMC Theaters are cleaning with Clorox products and marketing the partnership as a kind of seal of approval for safety. Uber is supplying its U.S. drivers with wipes, and customers get a notification if their ride has them.

This kind of branding is a marketer’s dream, but it's also a key to Rendle’s push to keep expanding a professional business that, while small at 8% of revenue, surged about 70% over the past two quarters. That division’s success, along with a push internationally, where it only generates 15% of sales, was part of the reason the company raised its long-term forecast 1 percentage point to 3% to 5% annual growth.

“Even if me as a consumer doesn’t feel I need to use these categories anymore, it seems likely that businesses will clean more to keep employees safe and make consumers feel safer,” said Carey, the Wells Fargo analyst who has the equivalent of a buy rating on the stock. “That’s really important because that’s white space for this business.”

Back in the Bay Area, Rendle sums up her vision for company over the next few years. She doesn’t want people to “worry about this stuff,” and sees Clorox providing a comfort blanket of sorts for when they do get back to traveling and movie theaters.

“We want people to return to the lives they had before,” she said. “I personally cannot wait to see a Warriors game live. It’s killing me."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.