Hong Kong’s Pro-Democracy Activists Are Running Out of Options

In just a year and a half, China has effectively brought Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement to a dead end.

(Bloomberg) -- In just a year and a half, China has effectively brought Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement to a dead end.

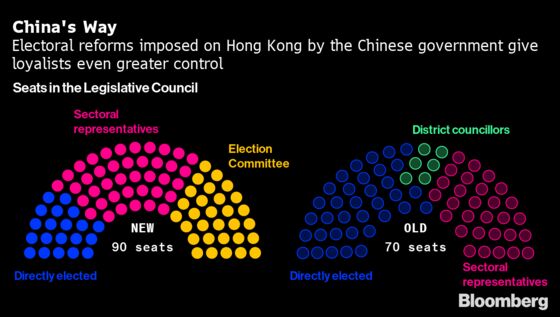

Almost all of the major groups advocating for meaningful elections and freedom of expression have disbanded, while this weekend’s vote for the Legislative Council — the first under China’s new rules — will feature only Beijing-vetted candidates.

Activists continue to seek new tactics, but the options are increasingly limited. Overseas activism, online petitions and demonstrations so small that campaigners are often outnumbered by the watching police: It’s all a long way from the historic mass protests that brought hundreds of thousands of people onto the streets in 2019.

The crackdown has “caught us off guard and exceeded the threshold of what we can bear,” said Joe Wong, chairman of the now disbanded Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, the city’s largest pro-democracy labor organization. “We need to think of new ways to cope with it.”

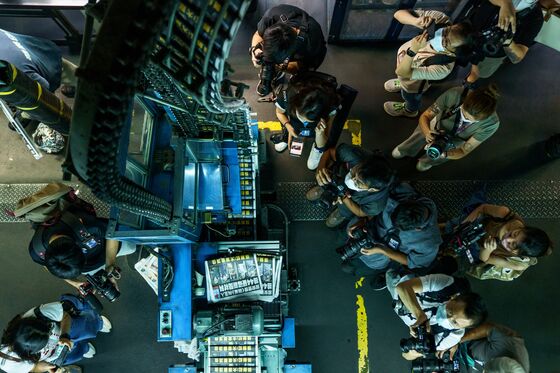

In the wake of the 2019 demonstrations, Beijing imposed a sweeping national security law on Hong Kong that criminalizes subversion, secession, colluding with foreign forces and terrorist activities. Since June 2020, more than 150 people have been arrested by the National Security Department; public assembly has been banned; the pro-democracy Apple Daily newspaper has been forced to close and Amnesty International has ceased operations, citing fear of “serious reprisals” under the law.

Even digital activism has become subdued. In 2019, social media and messaging apps were key tools for mobilizing demonstrators and discussing the movement. But over the past 18 months, once-popular groups and channels have largely emptied of users and new posts. Online platforms still carry news about protesters’ trials and discussions over issues like boycotting the government’s Covid-19 contact tracing app, which some fear could be used for surveillance purposes. A few jailed activists post updates on social media via friends and family. Meanwhile social media posts have been cited in national security trials and some account administrators have been placed under arrest.

The Dec. 19 election, however, features none of the pro-democracy figures that won seats in the last vote five years ago: Under Beijing’s new system, only “patriots” who “respect” Communist Party rule can run for office. While the Legislative Council was expanded to 90 members from 70, the number who are directly elected was reduced to 20 from 35. In the run-up to the vote, Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam declared that low voter turnout was actually a sign the government was doing well.

Among the opposition parties that will not contest seats is the League of Social Democrats, once known for its confrontational style in the legislative chamber. Chan Po-ying took over as chairperson in July after several core party members were jailed or awaiting trial — including her husband, veteran activist Leung “Long Hair” Kwok-hung, who is serving a 23-month sentence after attending unauthorized protests in 2019 and 2020.

“People ahead of me are all locked up,” Chan said. “I was happy working behind the scenes.”

Her party still demonstrates, but on a dramatically reduced scale. A group of four members — the largest public gathering allowed by city authorities due to Covid — is frequently seen outside government offices and courts carrying banners with the slogan “release all political prisoners.” There are often fewer protesters, or onlookers, than there are police.

The party’s three main tactics — street protests, judicial review and participating in the Legislative Council — “only work in an active and liberal social environment,” Chan said.

The same is true for other pro-democracy organizations in Hong Kong.

Before disbanding, HKCTU came under pressure from pro-Beijing newspapers, which accused it of provoking hatred towards the central government, receiving funds from foreign organizations and serving as an agent of foreign countries. The union’s leaders also faced personal threats and attacks, Wong said, without sharing details. Members ultimately felt it was too risky to continue fighting for labor rights, holding demonstrations and participating in local elections.

“We don’t think this is the end of our journey,” Vice Chairman Leo Tang said. “We are just marking the new start.” However Tang did not outline any specific plans, saying activists are more effective if they don’t reveal too much.

Ronson Chan, chairman of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, was less optimistic.

“We’re planning for the worst — but what is the worst, nowadays?” he said. “I am scared.”

The HKJA, which advocates for press freedom and journalists’ rights, is one of the few prominent civil society organizations still operating. While the national security law explicitly reaffirms freedom of the press, Apple Daily’s closure has had a chilling effect on the pro-democracy media, and numerous journalists have been arrested or been unable to renew their visas since it passed. The city ranked 80th in Reporters Without Borders’ 2021 press freedom index, down from 54th place a decade ago.

HKJA has no plans to alter its activities, but its board and members agree that if it can no longer speak up for journalists, they will reconsider its viability. Chinese state-media outlets have accused it of being “anti-China and bringing chaos to Hong Kong,” and Chan said membership has fallen by about one-third since 2019, to about 500 journalists.

“I can only foresee that the HKJA will still be fine until Christmas or before Chinese New Year,” he said.

The stress is also filtering through the “yellow economy” of businesses that have openly supported the movement. Chickeeduck, a clothing chain that last year displayed a banned pro-democracy slogan and a statue of Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, said it will exit the city in 2022, citing a pressure campaign by Beijing and Hong Kong authorities. Chinese officials have stopped mainland factories making its products, according to Chief Executive Officer Herbert Chow.

Hong Kong’s activists may soon face another legislative challenge: The city plans to introduce its own national security law in addition to the Beijing-drafted rules. When the government last attempted to enact Article 23, the bill prohibited “foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities” as well as “treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets.” The proposal was shelved in 2003 following huge street protests. The redrafted legislation may also criminalize spying activities.

“Those [campaigners] who still remain very active, they will feel the threat,” said Joseph Cheng, an activist and former politics professor at the City University of Hong Kong. He sees risks for professionals working in media, culture, entertainment “and even the financial services industry.”

The Security Bureau said it expects to conduct public consultation before the current term of government ends on June 30, 2022, and “will not set any expectations on the views received at this stage.” The bureau added it will “guard against any smearing on and efforts in demonising the legislative exercise.”

One remaining tactic is overseas activism. Campaigners like exiled activist Nathan Law and former lawmaker Ted Hui, who are now based in London, are able to comment more freely on events in Hong Kong and to lobby Western governments. Law spoke at U.S. President Joe Biden’s democracy conference last week.

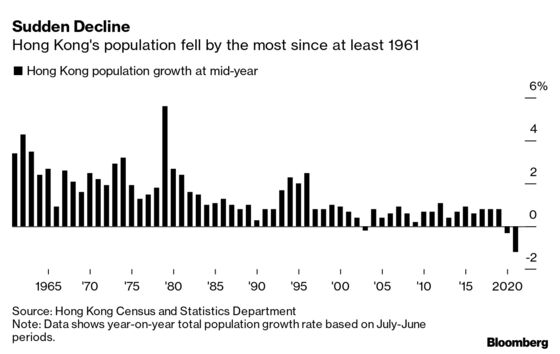

Professor Cheng expects such work to continue, especially as the number of people leaving the city for places like the U.S. and the U.K. grows.

However, “the performance of various pro-democracy groups working outside China in the decades since 1989 has not been impressive,” he said.

For some activists, the route forward seems to be a kind of cautious fatalism. HKCTU’s Tang, who spent two months in jail after the 2019 protests, said he was prepared to be imprisoned again. Chow Hang Tung, the vice chairperson of the organization behind an annual Tiananmen Square vigil, echoed the sentiment.

She was arrested in September after refusing to hand over information about the membership and finances of her group, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China.

“They can do whatever they want to me,” Chow said. “But that’s basic ethics in social activism — how can I hand in other people’s info to the police?”

With all seven of its core members in jail or custody, the Hong Kong Alliance disbanded the same month. On Monday, Chow was sentenced to 12 months in jail for attending and encouraging others to take part in a banned vigil last year to commemorate China’s 1989 crackdown on democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square.

Most of the activists interviewed say all is not lost yet. David Zweig, social science professor emeritus at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, disagrees.

“I think it’s over,” he said, adding that the jailing of opposition lawmaker Albert Ho “sends a pretty clear signal that even the moderate democrats will not have much room in the future of Hong Kong.”

“And the radicals, the protesters, the activists, they have no future,” he said.

Although she continues to campaign, the League of Social Democrats’s Chan is also pessimistic. “We are all walking on a tightrope,” she said. “If they want to get rid of you, they will, and they can.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.