Central Banks Have a $12 Billion Coal Problem They Must Solve

Think tank highlights financial-stability risks from fossil.

(Bloomberg) -- The world’s leading central banks should purge coal-related assets from their balance sheets and set rules discouraging the financial system from financing polluting industries, according to the New Economics Foundation.

A report by the London-based think tank estimates central banks in the euro area, the U.K., the U.S., Japan, China and Switzerland own more than $12 billion in bonds and stocks exposed to coal. That figure assumes the share of brown assets in those institution’s holdings is roughly equivalent to that in the Swiss National Bank’s U.S. equity portfolio -- the only publicly available data on private-sector investments by a central bank.

It’s a conservative approximation -- even in the author‘s opinion.

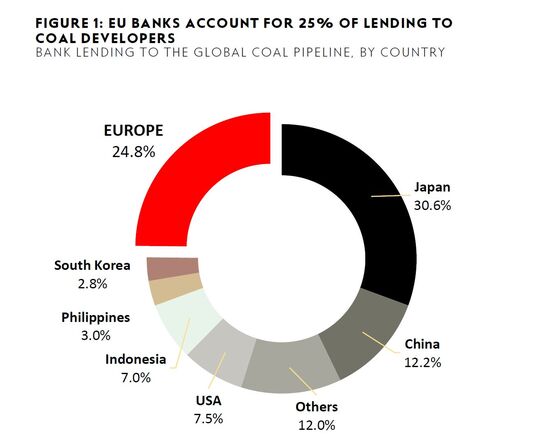

“If you look at U.S., Japan or China, they obviously have a huge amount of coal-fired power plants and that’s probably reflected in their central banks’ balance sheets,” said Frank van Lerven, an economist at the NEF.

His report focuses on coal as the largest source of greenhouse-gas emissions and notes that its use for power production would have to drop to nearly zero by 2050 to keep global temperature increases below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

As governments around the world investigate strategies to rein in climate change, central banks are at risk of ending up with stranded assets -- such as bonds of coal mines or refineries built to extract reserves that may soon be snubbed.

While policy makers have urged commercial banks they supervise to ensure their balance sheets can weather a transition to a lower-carbon economy, they themselves have insisted quantitative-easing portfolios and foreign-currency holdings are best managed if they reflect the market.

“Reducing exposure to coal assets is a low hanging fruit for central banks,” van Lerven said. “If central banks want to lead by example and practice what they preach then coal is the first place to start.”

This isn’t to say central banks are idle bystanders. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde committed to exploring ways to tackle climate change during the institution’s policy review. In the Network for Greening the Financial System, the ECB is working with more than 50 of its peers on researching potential policy solutions.

Crucial to any action is proceeding with caution.

“You don’t want to trigger transition risk by announcing tomorrow that you’re going to remove coal from your balance sheet,” said van Lerven, who is working with the NGFS. “Central banks have to be careful and manage this process gradually.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Piotr Skolimowski in Frankfurt at pskolimowski@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Jana Randow, Craig Stirling

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.