Cash-Strapped Pemex Delays Payments to Some Private Oil Partners

Cash-Strapped Pemex Delays Payments to Some Private Oil Partners

(Bloomberg) -- Petroleos Mexicanos is racking up millions of dollars in late payments to oil companies as it struggles to generate cash amid skyrocketing debt and weaker crude sales.

While Pemex has long sought to stretch its cash further by delaying payments to contractors, people with knowledge of the situation say it’s now also deferring reimbursement to some partner companies in an effort to postpone spending money that’s in increasingly short supply. Some private oil companies in Mexico sell their barrels to Pemex to mix with its own hydrocarbons for export because they lack the infrastructure and scale to sell the crude on their own, the people said, declining to be identified because they weren’t authorized to speak to the media.

The Mexican state-owned oil giant owed about $60 million as of April 30 for crude and natural gas to Egypt’s Cheiron Petroleum Corp. and about $4 million as of April 16 to Hokchi Energy, a Mexican subsidiary of Argentina’s Pan American Energy LLC, as well as undisclosed amounts to Wintershall Dea GmbH, according to people with knowledge of the situation, and company documents seen by Bloomberg.

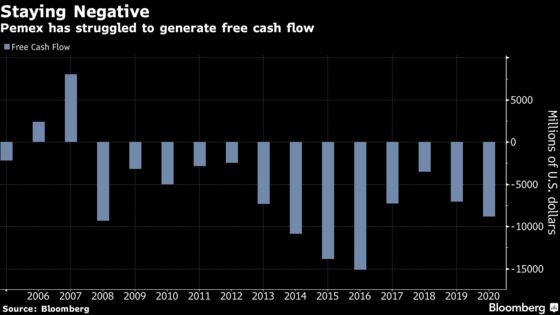

Pemex’s latest payment woes underscore the deteriorating state of its finances after more than a decade and a half of falling output due to underinvestment. It has had negative free cash flow every year since 2007, data compiled by Bloomberg show, and has amassed $113.9 billion of debt, far more than peers of a similar size or larger.

To be sure, Pemex’s bonds are rising amid an oil-market rebound, signaling growing confidence in the company’s finances as crude prices climb. The government-owned company has never defaulted on its debt. While deferred payments aren’t uncommon among state-owned producers in Latin America, delays in reimbursing partners could erode trust, making it even harder for the producer to stage a recovery, Francisco Monaldi, a lecturer in energy economics at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, said in a phone interview.

Representatives from Pemex didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment by phone and email. Cheiron didn’t respond to requests for comment made during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, when working hours in Egypt are limited.

Pemex owed Hokchi more than $4 million as of April 16 for oil and gas exports sold in December and January from its field by the same name, with the debt owed since mid-March of this year, according to the documents, and people familiar with the situation.

During the term of its contract with Hokchi Energy, “Pemex has made payments corresponding to the volumes of hydrocarbons delivered. Regardless of any specific delay, the relationship developed with Pemex is within the usual commercial terms,” Hokchi said in a statement. Hokchi didn’t specify whether payments for December and January exports had been made.

A Wintershall spokesman said the company has a “trustful partnership” with Pemex, referring to a joint venture at the onshore Ogarrio field, and work is ongoing to resolve the payment issue. Wintershall is the operator of the field, with a 50% stake.

The amount owed to Cheiron and Hokchi is small in the context of Pemex’s overall business, with the company reporting $15.6 billion in adjusted revenue in the first quarter. Still, some Cheiron debts have been owed since last year, meaning Pemex is in breach of its crude marketing agreements to pay invoices within 60 days of sale, according to the people, and documents from Cheiron and Pan American Energy seen by Bloomberg.

“This is certainly very concerning because such payment delays will eventually have a negative impact in both the partnerships and in oil investment and production,” Rice University’s Monaldi said.

Though the pandemic hammered oil producers across the globe as crude prices plummeted, Pemex’s budget woes have been years in the making. Covid-19 has strained the company’s balance sheet even further amid tumbling fuel demand, virus containment measures and a government austerity drive. The company’s 16-year consecutive stretch of production declines is unusual for a company of its size.

Pemex had negative free cash flow of $8.9 billion last year, up from negative $7 billion in 2019, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Moody’s Investors Service Inc. said much of the company’s pre-tax cash flow is consumed by taxes and duties, and its capital spending has had to fund debt, limiting its ability to reinvest in production and reserves. Moody’s expects that Pemex will continue to generate negative free cash flow in 2021 and will need more government support to address its financing needs. That’s in contrast to most of its peers in the industry, who have returned to profitability as crude prices rise.

Moody’s downgraded Pemex’s bonds to junk in April of last year, while Fitch Ratings Ltd. cut its bonds further into non-investment grade territory the same month. But the company’s bond prices have climbed amid a recovery in the oil market. In March, Pemex said it was working with contractors to optimize payments, though it hasn’t commented on debts to private partners. A Pemex default is unlikely because investors view the debt as an extension of the sovereign, and a default would have major repercussions for Mexico, said Luis Maizel, co-founder of LM Capital Group in San Diego, which holds Pemex bonds.

“It is not surprising that Pemex is late on its payments to partners because their cash flow is very tight,” Maizel said. “But if you ask me whether I think that this is the beginning of something worse the answer is no, because they are going to continue pumping and continue to pay investors. The government is not going to let Pemex default.”

Months of Unpaid Bills in Mexico Oil Patch Add to Pemex Woes (1)

Pemex owed about $60 million to Cheiron as of April 30 for the Cardenas-Mora onshore oil project, one of its first ever farm-out agreements, in which both partners have a 50% stake and Cheiron is the operator. The debts include money owed for crude that Pemex has sold from the joint venture, as well as operational expenditure and accrued interest, with some payments owed for more than a year, according to company documents.

Cheiron says it’s being shut out of tenders and business opportunities with Pemex, according to company documents. It has had to pay fines and penalties to Mexico’s oil regulator because of Pemex’s failure to pay royalties on their joint projects, and it claims that Cardenas-Mora is in financial jeopardy as a result of negligence on the part of Pemex, according to internal documents from Cheiron.

Private production

While Pemex continues to be the overwhelmingly dominant player, with almost 97% of oil production in the country, private firms hold as many as 111 oil and gas exploration and production contracts in Mexico. AMEXHI, the Mexican association of hydrocarbons producers, estimates that output from private companies in the country will rise about fivefold by 2024.

The payment delays are the latest challenge for the embryonic private oil industry in Mexico, which has increasingly come under fire from the government of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. The president known as AMLO has made it his mission to undo the 2013-2014 energy reforms that opened Mexico to private investment for the first time in almost eight decades, and return much of the oil sector back to the state.

One of his first actions since assuming the presidency in late 2018 was to cancel new oil auctions and farm-outs with Pemex. The much-lauded bid rounds had lured the world’s biggest drillers, including Exxon Mobil Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell Plc.

The situation adds to the “risks of partnering with Pemex,” said Monaldi. And for Pemex and Mexico, “less credibility means costlier deals in the future.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.