Can a Private-Equity Giant Invest in Oil While Saving the Planet?

Can a Private-Equity Giant Invest in Oil While Saving the Planet?

(Bloomberg) -- Carlyle Group Inc. bought a business that sells harsh chemical cleaning products to put streak-free shines on kitchen appliances and swiftly remove dried paint. Then private-equity executives set about changing the products and even the office lightbulbs. Now the company, Weiman Products, sells a line of cleaning sprays made to emphasize sustainability and appeal to eco-conscious shoppers. Business has improved, which should help when it’s time to sell the company.

This process plays out hundreds of times each year in the world of private equity, and an investor like Carlyle would be expected to tout improvements in revenue and profit margins. In this case, though, Carlyle also wants to position the deal as proof of its commitment to fighting climate change—and a demonstration that moneymaking private-equity investors can be a force for progress.

“We fundamentally think Weiman will be worth more upon exit because of this focus on the sustainability of their products,” says Megan Starr, the head of impact at New York-based Carlyle.

Starr’s job at Carlyle, which she joined last year, is to push environmental, social and governance (ESG) strategies throughout its $217 billion portfolio, even if these businesses aren’t easy to square with a commitment to the climate. That makes Carlyle’s approach different from private-equity rivals such as KKR & Co. and TPG Capital, which have set up dedicated impact funds targeting renewable energy and sustainable ventures. At Carlyle, investments in fossil-fuel production and cleaning chemicals are all supposed to be ways to make a better world.

The problem for private equity’s push into into ESG is what can be done to address business in all kinds of controversial areas, says Mark Campanale, founder of the Carbon Tracker Initiative. “I think the answer to that is ‘not very much,’ so long as pension funds and insurance funds still want to allocate to that area.” That legacy, for Carlyle, includes a minority stake in Combined Systems, a manufacturer of tear gas. Carlyle says it wouldn’t make such an investment today because it would violate the firm’s responsible investing guidelines.

A basic premise of the ESG movement is to discourage investment in companies that, for example, create heavy greenhouse-gas emissions. Carlyle finds itself among an emerging group of investors that believes in the ability to bring about positive change, even in some companies that would fare poorly on ESG measures. That raises a big question: Can private-equity investments in things that aren’t great for the planet actually be a force for good?

There wasn’t a single green cleaning product sold by Weiman in 2018. Unilever NV and other consumer-products companies had started moving aggressively to become more like businesses idealistic millennials would want to work for and environmentally-conscious shoppers would want to buy from. But Weiman had been sitting out the rise of green consumerism before Carlyle purchased the company in March 2019.

Carlyle worked with Weiman’s board for a year after the acquisition to ditch harsh chemicals. In the process, it bought two natural-cleaning brands, Green Gobbler and Bio-Kleen, and spent more than $750 million combining the three companies. The new Weiman had some products that qualified for a “safer choice” label issued by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The micromanaging reached into details about water use at factories and installing LED lights at corporate headquarters in Gurnee, Illinois.

It wasn’t that company executives didn’t want to go green before—they just didn’t really know how. Past attempts had been made to switch to lightweight packaging. But division managers would come up with scattered ideas and there were no real experts to help with execution, says Heather Gaspar, head of marketing and sustainability at Weiman.

Private equity brought both money and expertise. Jackie Roberts, a chemical engineer and operating executive at Carlyle, joined Weiman’s board and helped outline the range of possible green certifications. She even accompanied Weiman’s chief executive to meetings with Target Corp., a major customer. The company had been losing ground at Target and Walmart Inc., both of which are now seeking more transparency on suppliers’ carbon footprints. There were some questions Weiman executives didn’t know how to answer. Carlyle’s team helped explain how to fill out Walmart’s sustainability scorecard and how to calculate the footprint of their own supply chain.

“They have been so helpful,” says Gaspar. “I would say they are much more of a resource versus coming in and telling us how to sustainably run our business.”

ESG funds have exploded in popularity in recent years, and private capital has started moving in. KKR topped $1 billion for its first Global Impact fund last year, and TPG has a $2 billion Rise Fund aimed at impact investing. In part this a response to pressure from big investors like pension funds to face the risks of global warming. About a third of private-equity investors in the U.S. planned to modify portfolios in response to climate change, according to a November report by PE firm Coller Capital, and three out of five European and Asian private-equity investors planned a similar shift.

Response to this pressure can take the form of ditching companies that don’t do enough. The number of climate-related shareholder resolutions for oil companies ballooned last year, and it’s no longer just climate activists launching them. Other big investors, such as American and European banking giants, have bowed to pressure to stop financing some coal and drilling businesses.

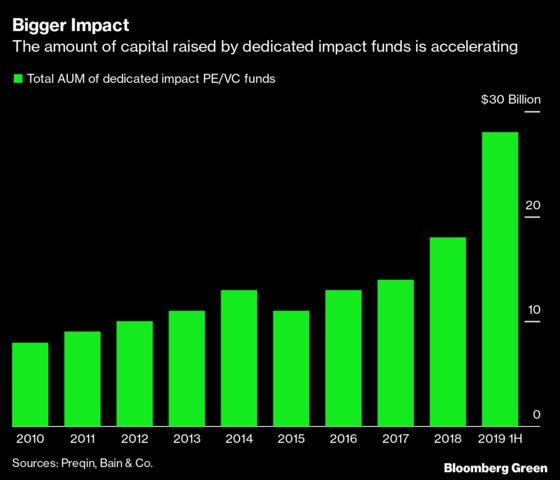

Embracing the ideas of ESG can also mean steering capital toward firms with strong environmental and social governance criteria. The amount of capital raised by dedicated impact funds in the first half of 2019 surged to $28 billion, up from $18 billion for the whole of 2018 and just $8 billion in 2010, according to consultants at Bain & Company.

Carlyle is among those taking an approach that includes impact investing, in which the promise of competitive returns comes with a promise of measurable impact. This means shaping businesses directly, rather than just investing in the good ones. By eschewing separate funds in favor of applying ESG strategies throughout its entire portfolio, Carlyle is trying to replicate what has traditionally only been achieved by niche firms like Leapfrog Investments or Bamboo Capital Partners.

For Carlyle, this strategy doesn’t exclude significant backing for fossil fuels or other businesses that don’t align with climate considerations. As recently as October 2019, six months after setting out on the green transformation of Weiman, Carlyle joined with oil veterans to launch Boru Energy, a venture targeting as much as $1 billion in fossil-fuel deals across sub-Saharan Africa. Carlyle made a 2018 investment in Neptune Energy, one of the world’s largest private fossil-fuel explorers and producers, and now touts the company’s below-average emissions. Carlyle likewise isn’t among the more than 3,150 signatories to the U.N.-backed Principles for Responsible Investment—although 450 signatories have some kind of private-equity exposure. (Rivals such as KKR and Neuberger Berman Group have signed.)

Beyond the climate consequences of private-equity decisions, there’s also Carlyle’s origins as an investor in military communications and electronic-warfare systems. “You could apply the highest ESG principles to your investments into the defense industry,” says Carbon Tracker’s Campanale, “but they’re still going to be socially negative.”

Starr says critics are justified in asking how Carlyle can at once back fossil fuels and tackle climate change. But in her view, there’s no longer a choice between making money and being green. Carlyle doesn’t like to divide companies into good and bad, she says, preferring to embrace a stripped-down definition of sustainability.

“People hear the word sustainable and they think just green. Actually sustainable literally means the ability to persist over time,” Starr says. “If you are a company that's capturing consumer preferences, if you're the company that has the best shelf space and you're the company that is creating the best goods that customers are going to have loyalty to, that's a much more sustainable business model.”

From that perspective, it may not matter much to Carlyle executives that natural cleaning products aren’t always better for the environment than petrochemical products. Tom Welton, a professor of sustainable chemistry at Imperial College London, has worked on assessments of the environmental footprint of cleaning goods. Often, he finds, what matters most is how consumers use it—whether we fill up the washing machine with excess detergent matters more than the detergent’s formula. Consumers tend to focus more on ingredients than packaging materials, manufacturing practices and transportation, all of which can give a “natural” cleaning product more environmental cost than a synthetic alternative.

Still, consumer demand for organic and sustainable brands had been growing before the global pandemic, and market researchers Nielsen project more growth in the future. At the start of the outbreak, Weiman refocused its attention on products that could kill the coronavirus but says it remains committed to its new green plan.

A year after Carlyle took over, the firm reports that 27% of Weiman’s sales are green products—up from zero at the start. The board of the cleaning-products company approved a sustainability strategy to boost product stewardship and cut the manufacturing footprint while advancing community engagement. There’s now a sustainability update at each board meeting. Ingredients have been changed and disclosures improved. Weiman now counts four products certified as “EPA Safer Choice,” and the goal is to reach 30 by October. Target bestowed its “Target Clean” icon to all nine Weiman items it stocks.

Of course, the investment in Weiman is just a tiny fraction of Carlyle’s portfolio. It’s one small example of the influence of private equity.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.