Nordea Money Flows Questioned as Browder Seeks Nordic Probes

Nordea Money Flows Questioned as Browder Seeks Nordic Probes

(Bloomberg) -- Nordea Bank Abp, Scandinavia’s biggest lender, now risks being dragged into a money laundering scandal that has rocked the Nordic and Baltic region.

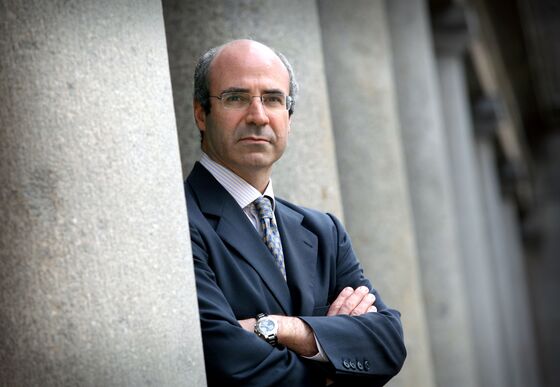

Bill Browder, the U.K.-based investor tracking dirty money flows out of Russia, has filed complaints with Nordic prosecutors alleging he can pinpoint 365 Nordea accounts in Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway that received $175 million from shell companies set up to launder money and evade taxes from 2007 into 2013.

“Any decent due diligence would have caught this stuff,” Browder said in an interview this week. “There’s strong suspicion of money laundering there based on this information, and we’re asking law enforcement to investigate.”

Nordea, which moved its headquarters to Helsinki from Stockholm on Oct. 1, said that it was “aware” of Browder’s report and works closely with relevant authorities in the countries where it operates. Nordea shares dropped as much as 4.5 percent on Wednesday, and are down 14 percent this year.

While it can’t comment on individual customers because of banking secrecy rules, Nordea said it has “during the last years invested heavily in strengthening its resources to counter money laundering and other forms of financial crime across all countries where we operate.”

Though dwarfed by allegations against Danske Bank A/S, the region’s second-largest bank, the complaints could escalate the money-laundering scandal racking the Nordic region by drawing in its largest financial institution.

Browder also played a key role in the pressure that has built on Danske Bank, which now faces investigations in five countries, including in the U.S., after concluding that a large part of 200 billion euros ($231 billion) in transactions that flowed through an Estonian unit over a nine-year period were suspicious. Its chief executive officer resigned earlier this month and the bank’s shares have plunged more than 40 percent this year.

In an interview earlier this month, Nordea Chief Risk Officer Julie Galbo said she couldn’t rule out that the bank had been used to launder money, but pointed out that Nordea has beefed up monitoring and rid itself of risky portfolios since being fined by Swedish authorities three years ago.

The allegations against Nordea are the latest in a string of money laundering scandals that has lawmakers calling for tougher sanctions against banks and a stronger, European-wide system. While non-European banks have also been implicated and violated sanctions, “European banks appear over-represented in such cases,” S&P Global Ratings said in an Oct. 16 review.

According to Browder’s complaint, gleaned from information in other court cases, the fake companies that sent money to Nordea were drawing on accounts they had at Danske’s Estonian branch and Lithuania-based Ukio Bank. The shell companies then either funneled the money into accounts elsewhere or used it on both fake and real products and services, including furs, furniture and computer equipment.

The Baltic countries were simply “way stations” for illicit funds moving out of Russia, according to Browder. The investor has spent much of the last decade tracking down $230 million he says was laundered as part of an elaborate tax fraud uncovered by his attorney, Sergei Magnitsky, who died under suspicious circumstances in a Russian prison in 2009.

Danske Bank has closed the Estonia non-resident operations that were the hub of the laundering while Ukio Bank was declared bankrupt in 2013.

“It’s clear there was something deeply bent going on inside Danske Bank,” Browder said. “But we don’t know enough yet to make any conclusions about Nordea, which is one of the reasons” for asking prosecutors to investigate, he said.

The Nordea account holders in the four Nordic countries were both real businesses and fictitious companies and the complaint alleges that Nordea employees should have know what was going on. The “substantial” amount of accounts, the sophistication of transactions, the source of funds from Estonia and Lithuania from companies that conducted no business should have raised suspicions, it alleges.

Details from the Oct. 12 complaint:

- 128 account holders at Ukio sent $151 million to 287 Nordea accounts in Denmark

- 9 accounts at Ukio sent $9 million to 18 Nordea accounts in Norway

- 16 accounts at Danske’s Estonian branch sent $15 million to 60 Nordea accounts in Sweden, Denmark and Finland

Browder has previously asked for an investigation into Nordea. In 2013, he asked the Danish State Prosecutor for Serious Economic and International Crime to probe two accounts that had received funds from Danske’s Estonian branch and Ukio. Denmark declined to investigate, according to the complaint.

Niklas Ahlgren, spokesman for Sweden’s Economic Crime Authority, said in an email that the agency is looking into who has the jurisdiction to look into Browder’s claims after which a decision will be made on whether to pursue an investigation.

Danish and Norwegian prosecutors also both acknowledged that they had received the complaint and would look into whether further action is needed. Danish authorities are already investigating Nordea, after the Danish FSA reported the bank to police in 2016 for possible laundering breaches.

Finland’s National Bureau of Investigation said it hasn’t yet received a request to investigate, but Browder has said he would be filing a complaint in Finland soon.

--With assistance from Niklas Magnusson.

To contact the reporter on this story: Frances Schwartzkopff in Copenhagen at fschwartzko1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jonas Bergman at jbergman@bloomberg.net, Kati Pohjanpalo

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.