Brookfield Shuns ‘Eat-What-You-Kill’ in Private Equity Build-Out

Brookfield Shuns ‘Eat-What-You-Kill’ in Private Equity Build-Out

(Bloomberg) -- Brookfield Asset Management Inc. aims to build a private-equity juggernaut with a distinctly non-Wall Street feel.

An ethos of collaboration is deeply rooted in the 120-year-old Canadian firm and permeates its open-floor offices worldwide, top executives say.

“It’s the opposite of an eat-what-you-kill mentality,” Ron Bloom, a managing partner in Brookfield’s private equity group, said in an interview at Bloomberg’s headquarters in New York. “Collaboration is the norm. People who aren’t willing to work collaboratively just don’t like it.”

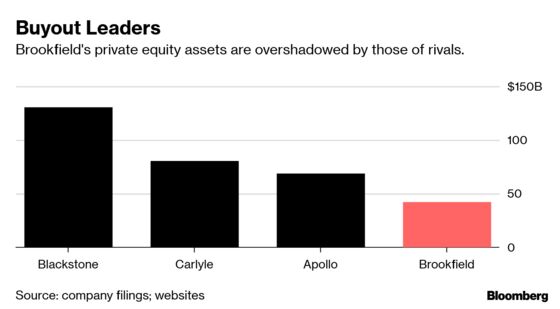

That culture is getting tested as the Toronto-based company sets out to transform its $42 billion private-equity business, now its smallest, into a giant. Brookfield, which also has real estate, infrastructure and renewable energy divisions, added to its quiver by agreeing earlier this month to buy Oaktree Capital Group, mostly a credit shop.

In the Canadian firm’s build-out of its traditional buyout business, it’s squaring off against several rivals with more than $60 billion each dedicated to private equity as of the fourth quarter.

“The big risk is that it’s a pretty competitive space these days,” said Devin Dodge, an analyst with Bank of Montreal in Toronto. Brookfield has “a great track record but in order to really beef up the scale, obviously you need to find larger deals.”

Name Recognition

Cyrus Madon, who heads Brookfield’s private equity, says he expects his division to eventually rival any other at the company. Real estate is the largest, with $188 billion in assets.

For the build-out, Madon can commit capital from Brookfield’s balance sheet, raise outside money and tap more than 180 professionals in North and South America, Europe, Australia, India, China and Japan to help make acquisitions.

Brookfield victories in a number of competitive deals have helped raise its profile as well, Madon said during the interview. It won the bidding for the car-battery division of Johnson Controls International Plc in November for $13.2 billion and hospital operator Healthscope Ltd. in January for about $3.1 billion.

“Compared to 20 years ago, we have far more name recognition,” said Madon, who has been with the firm since 1998. “The fact that our other businesses are global leaders positions us well in private equity to become a global leader as well.”

Raising a Fund

The firm has a ways to go to reach that goal. It’s now raising its next private equity fund, which is expected to be about $9 billion, Bloomberg has reported. The first close occurred at $7 billion, Brookfield said in February. The private equity division has posted gross returns of 29 percent, the firm also announced.

With the industry sitting on more than $1 trillion of undeployed capital as of September in a market with high assets prices, spending that money has become trickier.

“There is a lot of dry powder, and the market is always competitive,” Mark Weinberg, another managing partner in the group, said during the interview. “But you have to focus on our your competitive advantage.”

For Brookfield, that means engaging in the unglamorous work of improving the operations of the assets it buys. Weinberg pointed to Brookfield’s acquisition of Westinghouse Electric Co. out of bankruptcy last year for $4.6 billion as an example.

War Room

Before buying the former nuclear powerhouse, Brookfield drew on the expertise of its bankruptcy restructuring, infrastructure and energy businesses to assemble a group from around the globe in the “war room.”

They looked at every nuclear reactor that Westinghouse, a fuel and technology supplier, did business with to determine the health of its customer base. They also developed a strategy for the company to refocus its efforts on reducing bottlenecks, chasing profitability over market share and sales, and getting out of reactor construction that led to its bankruptcy.

“The model of deal guy buying the company and giving the keys to the operating guy once the deal is done, is the opposite of what we do,” Weinberg said. “We lead from operations.”

As Brookfield expands its buyout business, Madon says, it’s particularly interested in places like Brazil or India, where troubled financial institutions are putting stress on the system and forcing companies to sell assets to pay down debt.

What’s not changing at Brookfield is its culture, Bloom says.

“Our young folk are as ambitious as anywhere,” the managing partner said. “But they are prepared to exercise their initiative in a collaborative way. Other people aren’t and that’s fine. But they’re not the men and women we’re going to hire.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Scott Deveau in New York at sdeveau2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Elizabeth Fournier at efournier5@bloomberg.net, Vincent Bielski, Josh Friedman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.