(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President-elect Joe Biden’s selection of Brian Deese to lead the National Economic Council is likely to renew long-standing arguments about whether the private sector can be trusted to help combat climate change and how much business should influence public policy. The answer is there’s plenty of work to go around for both sides when it comes to climate change.

Deese will rejoin the White House from his perch at Wall Street titan BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest money manager. BlackRock plucked Deese from the Obama administration, where he served as senior climate and energy adviser, to lead the firm’s sustainable investing. While there, he helped develop a new tool, unveiled this week, that allows BlackRock’s clients to better assess the climate risks lurking in their portfolios.

Scientists have warned for decades that climate change would have a devastating impact on the economy and businesses, and those warnings have proved prescient in recent years. Natural disasters linked to climate change, from wildfires in Australia and California to flooding in America’s southern states to typhoons in Japan, were responsible for an estimated $150 billion in losses in 2019. Insurance companies, for one, are bracing for more severe weather and heftier losses ahead.

Of course, not all companies are equally exposed to climate risk. On the frontlines are those that rely heavily on physical assets, such as mining companies at risk of heat waves or utility companies in the path of wildfires or manufacturers situated near coasts vulnerable to rising sea levels. Not far behind are industries that contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, the big one being fossil fuels that power manufacturing, transportation and commercial and residential buildings. As businesses and consumers pivot to new and cleaner sources of energy, fossil fuels may go the way of, well, pick your outdated technology.

On the flip side, companies that are more safely situated, operate in the cloud or provide renewable energy are safer and stand to profit from efforts to reduce emissions. So investors are smart to think about which companies are which.

And BlackRock has been thinking about just that, or at least signaling to investors that it has. Deese has been deeply involved in the development of BlackRock’s new climate risk analytics, according to the firm, no doubt bringing his climate policy chops to bear. His return to Washington is an opportunity in the other direction — for policy makers to be better informed about the private sector’s contributions to the fight against climate change and to use that knowledge to fashion smarter, more efficient and more surgical climate policy.

Admittedly, not everyone will see it that way. The revolving door between government and industry, where business executives take senior roles in government and the other way around, is often maligned for clearing the way to naked conflicts of interest. Climate warriors are already complaining that Deese’s affiliation with BlackRock means he’s too cozy with business to be entrusted with climate policy.

While conflicts are a legitimate concern, much of the criticism isn’t about Deese — it’s about the fact that BlackRock oversees money invested in fossil fuels, which misses the basic function of money management. At its core, BlackRock invests the way its clients want, and most investors want a risk-managed, diversified portfolio that more or less reflects broad markets. As long as the market includes fossil fuel companies, some investors will inevitably be invested in them through intermediaries like BlackRock.

By the same token, as investors become savvier about climate risk, more of them will want to sidestep those risks by avoiding fossil fuels and companies that are most vulnerable to climate change. In that regard, climate warriors should view intermediaries like BlackRock as an opportunity to accelerate change by raising awareness among investors and thereby feeding money to companies that are serious about change. And who better to advise them than climate scientists and policy wonks, many of whom serve in government.

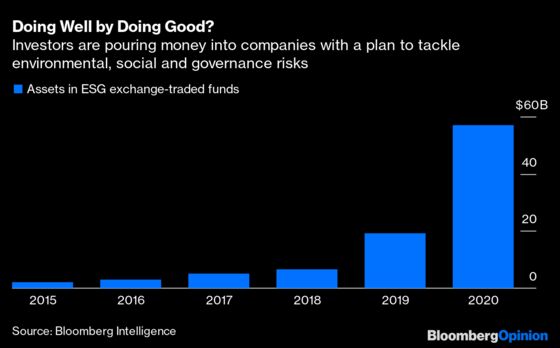

In fact, money is already moving. The U.S. energy sector, which is still dominated by fossil fuels, accounts for less than 3% of the S&P 500 Index, down from 7% five years ago and 12% a decade ago. Investors are also increasingly embracing ESG, which aims to invest in companies with environmental, social and governance policies that are expected to make their stocks safer and possibly more lucrative. There’s roughly $57 billion invested in ESG exchange-traded funds today, according to Bloomberg Intelligence, up from just $2 billion five years ago.

There’s no guarantee that moving money around will help the fight against climate change. But it’s one example of how the private sector can contribute. It’s fantasy to think that government alone can tackle a problem as big and complex as climate change. Accepting that, coordination between government and business around climate change should be applauded, not derided.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.