Brazil Wants Amazon Critics to Put Money Where Their Mouth Is

Brazil Wants Amazon Critics to Put Money Where Their Mouth Is

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil is looking past the environmental fights with the international community that marked President Jair Bolsonaro’s first year in office and increasingly calling on investors and companies to help protect the Amazon, according to the country’s environment minister.

Ricardo Salles has been developing a series of plans that, as he described, will give critics a chance to put their money where their mouth is. The government is setting up three different investment funds, which should provide about $250 million in environmental financing, and setting aside 15% of the rainforest for preservation, which could bring in another 630 million euros ($747 million) in private investor money per year.

“It is an important change for the government and we will see who will really help,” he said in his cabinet in Brasilia. “If there was a criticism that the government was not open to outside help, this criticism no longer makes sense; there are several possibilities on the table for those who want to help.”

The change in strategy comes as the ministry is faced with simultaneous pressures: a deterioration in the country’s green credentials that started to impact investment and exports, and the stinging reality that money to manage the environment will need to come from the private sector as government revenue crashes during the pandemic.

After the global outrage caused by Amazon fires last year, a group of institutional investors managing about $3.7 trillion in assets signed a letter in June threatening to pull back investments if no action was taken. Brazil’s central bank director for international affairs, Fernanda Nechio, called the letter an “important signal” that Brazil needs to be transparent about its “plan of action” on the environment. Marfrig Global Foods SA, one of the world’s biggest beef suppliers, is planning to track cattle ranches in parts of the Amazon and trying to convince the government to follow the move.

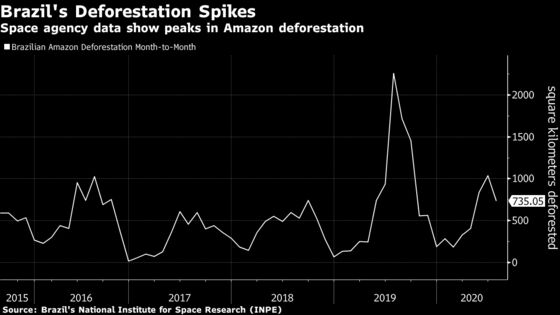

Meanwhile, government data show deforestation continues to rise: it increased 33% from August of last year to the start of August this year, according to data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). As Brazil enters its dry season, fires are sweeping through the forest again, although global oversight of the Amazon has been weaker because the pandemic diverts much of the attention from environmental matters.

“More and more investors are realizing that preventing the climate crisis is really crucial to our long-term returns,” said Kate Monahan, shareholder engagement manager for Friends Fiduciary Corporation, one of the funds that has signed onto letters expressing concern for Brazil’s environmental policies. “We see deforestation posing reputational and legal risks to our portfolio companies, specifically in the food and agriculture sector.”

Adopt a Park

This week, the government will launch the “Adopt a Park” program that will allow investment funds and private entities to sponsor the preservation of plots of land for the price of 10 euros per hectare. The 15% of the rainforest, equivalent to some 155 million acres, is already split into 132 conservation areas where commercial exploitation is prohibited, but the government can’t afford to properly monitor it.

Salles said the ministry is also partnering with investment funds to create three programs totaling $246 million for environmental stewardship. One, which is already operational with $96 million, will reward small farmers and local communities in the Amazon for preservation measures, including stopping using fire as a way to clear land. Another $100 million fund will be available to finance biodiversity and bioeconomy projects. The third -- with an initial contribution of $50 million -- will finance bioeconomy projects by Amazonian countries and large companies and will be managed by the Inter-American Development Bank.

The minister specifically called out Brazil’s big banks: “It is a complete change and an opportunity for Bradesco, Itau, Santander and international funds that were critical to adopt these areas in the Amazon.”

Brazilian banks and some of the country’s biggest companies have followed the lead of international investors and increased the pushback against the government’s environmental policies. A group of 61 companies including crop giant Cargill and pulp maker Suzano sent a letter to the government in July saying the negative environmental perceptions are potentially damaging to both reputation and business prospects. It later requested Congress take actions to solve issues involving, among others, land-title regularization and illegal deforestation.

“The private sector has gotten together and given the topic more preeminence,” Roberto de Oliveira Marques, the chief executive officer of cosmetics maker Natura & Co Holding SA, said in an interview. About the government, he said there’s been “more dialogue on some fronts, and the awareness that it is important.”

Another attempt to change the global narrative about Brazil’s commitment to the environment came in the beginning of the year, when Bolsonaro put Vice President Hamilton Mourao in charge of a new Amazon Council intended to coordinate efforts to stop illegal deforestation. One of the outcomes of the retired general’s effort was a decree sending military troops to the region to investigate and combat fires and illegal deforestation.

Setbacks to that strategy often come from members of Bolsonaro’s administration, however. In a video of an April cabinet meeting -- which became public in May amid the exit of a high-profile minister -- Salles could be heard saying the government should take advantage of “the opportunity that we have, that the press is giving us a moment of calm in terms of media coverage, because it’s only covering Covid, to get the cattle grazing and changing all the regulation and simplifying the rules.” His comments outraged environmentalists who saw them as evidence of the government’s true intentions.

Brazil’s change in tone may also reflect economic interests rather than political positions, said Isabela Kalil, a professor researching Bolsonaro’s politics at the School of Sociology and Politics of Sao Paulo.

“I think this change is more about appearance than a change in the politics of the state or that Bolsonaro has effectively, for some reason, changed his position,” she said.

In the interview, Salles maintained the administration’s critique of Europe’s involvement in the carbon credit market.

“The European protectionism of carbon credit is preventing Brazil from receiving fundamental resources to care for the forest,” he said. He called for negotiations to be resumed before the COP21 meeting in Scotland, scheduled for November 2021.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.