Brazil Has 109 Million Black People. Not One Runs a Big Bank

Brazil Has 109 Million Black People. Not One Runs a Big Bank

(Bloomberg) -- Last month, when much of the world was focused on anti-racism demonstrations in the U.S., Brazil’s biggest cable news channel held a prime-time discussion on them with six commentators. Many watching were struck by one thing -- in a country that is more than half Black and Brown, all of the panelists were White.

Many nations are seeing their own racial disparity reflected in the U.S. reckoning. But with the second-largest Black population in the world (after Nigeria), Brazil is unlike any other. Its power structure is almost entirely White -- not a single Black government minister -- with limited public attention to racial inequality.

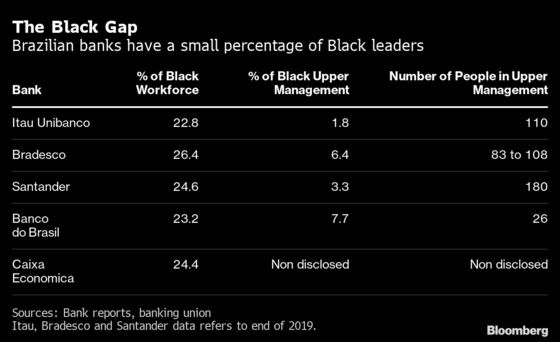

It’s an imbalance fully evident in the financial sector. No big bank in Latin America’s largest economy, a nation of almost 210 million, has a Black chief executive officer or board member. The percentage of Black upper management in major banking is similar to that in the U.S. (whose Black population is 13%) -- 3%.

“We’re definitely a racist nation,” lamented Vanessa Lobato, vice president for human resources at Banco Santander Brasil SA.

You won’t hear otherwise from Haroldo Nascimento, 36, who’s a manager for retail strategy at Banco Bradesco SA, one of Latin America’s biggest banks. Nascimento, who is Black, arrived at a management conference in Sao Paulo when a White man pulled up in a car and handed him the keys.

Nascimento threw them to the ground.

“Don’t you work here?” the man asked.

“No, do you?” Nascimento replied, and walked away.

And yet, as anyone who’s spent even an hour in Brazil can attest, the mixing of races is unmatched virtually anywhere. The nation’s rhythm, its culture, sport and cuisine, its very soul, is infused with Africa. This paradox -- that the nation’s cultural majority is a downtrodden economic minority -- has made grappling with race so challenging, according to experts.

As in the U.S., racism has origins in slavery. Some 40% of all enslaved Africans shipped to the Americas were sent to Brazil. It was the last country to ban the practice, in 1888, and it then lured Europeans to “whiten” its society.

Unlike the U.S., Brazil has never had legal codes segregating schools or public transport. That’s led many to insist that there’s really no problem, that Brazil is a “racial democracy” with no comparison to the U.S. That also helps explaining why the recent global protests over racial discrimination yielded only smaller demonstrations there.

One who argues that discrimination wasn’t a major issue in his career is Edilson Dias dos Reis, director of systems at Bradesco, one of the very few Black directors at a big bank. Reis says he faced no open racism on his rise and attributes his success to his mother’s sacrifices and his own hard work, which he urges upon Black trainees. “Discipline helps,” he said.

The data suggest a more systemic set of problems. Among the 10% of Brazil’s population with the lowest income per capita, 75% are Black, according to the national statistics bureau. A 2016 study by the nonprofit Instituto Ethos found that of the 500 biggest companies, Blacks hold 4.7% of upper management positions. Black women are 0.4%.

About 24% of the nation’s five biggest banks’ employees are Black, according to data compiled by Bloomberg and the banking-workers’ union based on regulatory filings.

“Companies’ recruiting processes usually discard Black people right at the beginning,” said Roberta Silva, head of fiduciary management services at Itau Unibanco Holding SA’s wealth-management unit, who is Black.

There are many reasons. The richest 18% of students -- nearly all Whites -- go to private schools that emphasize English and career development, easing them into spots in the university system where banks recruit. Lower-class Brazilians, mostly Blacks, are often made to work by their families to help supply basic needs.

There are subtler factors, too. While buildings have never had separate entrances based on race (as some in the U.S. once had), most relegate service visitors to a back way. The vast majority of them are Black.

Nascimento, the Black banking executive, said all these issues create barriers to getting into finance and a glass ceiling once there. But he’s also part of recent efforts to improve things.

Nascimento made it to Bradesco through a program that recruits at a college for Black students and provides them extra education. More than 450 have joined the bank from it so far. Nascimento is a mentor at a Black diversity group at Bradesco called AfroBra.

Pay Metrics

At Santander, increasing the number of Black employees is now part of executive pay metrics, Lobato said. The bank’s goal is to have a 30% Black workforce by 2021. Measures include training and changing recruiting procedures. She said the number of Black applicants for intern programs drops dramatically when they have to submit a video of themselves. They are convinced their race will disqualify them from consideration.

Itau has decided to avoid asking for English knowledge or a college degree when hiring for its technology area, providing the skills needed once inside the bank. Last year, it launched a 100-person, 12-month mentoring program for Blacks with directors and executive directors, said Valeria Marretto, human resources director.

“Both clients and employees need to see that Black people can thrive at banks,” said Bruno Scaldaferri, 38, who is Black and spent 17 years at Santander branches in the Northeast before becoming its head of diversity last year.

Such programs are growing but remain limited. President Jair Bolsonaro campaigned against the few affirmative-action programs in the civil service and higher education, although he hasn’t touched them.

Because the problem is both economic and social, Blacks in finance face a range of difficulties.

Itau’s Silva, 42, says her own father was a bank executive and she attended private schools. Classmates mocked her hair and called her “stinky little Black girl.” She adds that at work, “I feel I’m always having to break stereotypes.”

She recounted being approached recently by the head of another division at the bank who asked her to talk to his Black intern. The intern was talented but closing himself off. When she spoke to him, he told her he felt like a fish out of water because his peers spend as much on lunch as his mother does on groceries for a month.

Jaqueline Conceicao da Silva, executive director at Coletivo Di Jeje, which offers training in racial issues to teachers and companies, says beyond hiring, banks could do more by following a U.S. example and lending to minority-run businesses. “This is nonexistent in Brazil,” she said.

There’s clearly a long way to go. But the recent unrest in the U.S. may be jump-starting something. There have been small anti-racism demonstrations. And after social media erupted over the all-White TV panel last month, the network brought in an all-Black team the following night, saying it had “heard the message.” Two Black women are now part of the show’s permanent roster of commentators.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.