Brand-Name Companies, No-Name Workers: How ‘Ghosts’ at Contractors Keep ICE at Bay

Brand-Name Companies, No-Name Workers: How ‘Ghosts’ at Contractors Keep ICE at Bay

(Bloomberg) -- Seven days a week, Martha Lopez arrived before dawn at the Target in Brentwood, Tennessee, to make sure the store in the Nashville suburb gleamed for shoppers. For about two years, Lopez said, she emptied trash, scrubbed the toilets and polished the white floors to maintain the “wet look” the retailer demands. The pay wasn’t bad, but payday gave her pause.

Twice a month, her wages—$11.50 an hour—were loaded onto an electronic pay card that she’d been given. The card was stamped with somebody else’s name: “M Hernandez Cleme.”

Lopez didn’t ask questions. As an undocumented immigrant, she’d learned long ago to accept all kinds of oddities and indignities at work. Then earlier this year, the pay card stopped working. She complained to her boss and, eventually, got a new one. This one had no name on it. Lopez lost several weeks’ pay in the transition, she said, but her boss told her she could gripe all she wanted—no one would listen. She’d been working under the name of a person who’d come and gone long ago, she recalled him saying, so there would never be any record that she’d even picked up a broom on this job.

“They always told me I didn’t exist on their system,” Lopez said. “Como una fantasma.” Like a ghost.

Lopez wasn’t working directly for Target, but for a company called Diversified Maintenance Systems LLC that has had contracts to clean Target Corp. stores across the country since 2003. The company has faced serious allegations of labor violations in lawsuits and regulatory actions previously—including claims that it put undocumented immigrants to work under assumed names, as Lopez describes.

Amid the searing debate over President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown, Diversified and other contractors have provided a way for some of America’s biggest employers—including Target and Walmart Inc.—to effectively benefit from cheap, undocumented labor without fear of meaningful penalties. Diversified, Walmart and Target all say they don’t hire undocumented workers.

It’s illegal, of course, to hire such workers, but the law says an employer must “knowingly” make the hires to be in violation. That language has created opportunities for U.S. staffing companies, an industry that employs an estimated 15 million people. As they provide major U.S. companies with workers for the dirty, low-paid or dangerous jobs that few Americans want, many such firms also give their clients something else: plausible deniability regarding the workers’ immigration status.

A Bloomberg News investigation found that this backdoor labor supply sometimes involves the use of assumed names, including those of former workers. In one case, undocumented Venezuelans helped repair a storm-damaged Walmart, but the contractor for that job said a subcontractor supplied the workers and should be held responsible. That template—using layers of contractors—can frustrate attempts to hold companies accountable. Despite Trump’s call for stepped-up enforcement, it’s been rare for federal agents to unearth corporate wrongdoing in such arrangements. When they do, it’s rarer still for any executives to face consequences.

Some labor contractors “are kind of like a shield for major companies that are bringing in immigrant labor,” said Tim Bell, executive director at the Chicago Workers’ Collaborative, an advocacy group for temp workers. “They reap the fruits of their labor but don’t take on any potential liability that that kind of hiring would incur—liability for violations of labor laws, such as discrimination, wage theft, dangerous workplaces and sexual harassment.”

A few days after Bloomberg asked about Lopez’s case, Target this month said it would cancel its contract with Diversified in Tennessee and order heightened scrutiny of all the firm’s work. Allegations of Diversified’s use of undocumented immigrants in Target stores previously came to light in a workers’ lawsuit in 2011 and again more than a year ago. Yet Target retained Diversified then.

In a sense, the retailer’s decision to now take a closer look traces to a morning in mid-October when Lopez walked into Target’s Brentwood store—not through the employee entrance, but through the automatic front doors, right by Target’s big, crimson bulls-eye insignia.

She had grown desperate to recover her back wages, which she said amounted to almost $4,000 for more than a month’s work. She needed the money for her three children still living in Mexico. She’d been sending them cash for almost 20 years, ever since she followed a coyote across the desert into California. Now, all she could do was draw up the courage to demand it.

It isn’t difficult for an undocumented immigrant to get a job as a contract laborer in one of America’s blue-chip employers.

Labor contractors use informal recruiting networks that depend on WhatsApp text-message groups, Facebook pages or simple bulletin boards hanging in neighborhood markets. They hire brokers who know how to tap the latest wave of immigrants, such as Venezuelans fleeing economic collapse.

“It’s easy, let me show you,” said Jose C., a 22-year-old undocumented Venezuelan immigrant who settled in central Florida in February. A friend explained that to get a job, Jose needed a Mickey—their slang for a fake residency permit, or green card—and she sent him to the local go-to guy. “Here’s all I did,” Jose said, pausing from dinner at a Disney World sushi restaurant to type a message in Spanish on WhatsApp: “Hi, how are you? I wanted to know the procedure for getting a Mickey.” A response came in eight minutes: “I need a photo name last name and date of birth.”

“And the price?” Jose asked. The reply: “$120.”

“That’s how I got this,” he said, pulling a Mickey out of his wallet. It resembles a U.S. green card printed on white plastic. A piece of black tape across the back mimics the genuine document’s magnetic strip. The photo of Jose is blurry and distorted. “This is so ridiculously fake,” said Jose, who asked that his full name not be used for fear of being targeted by immigration authorities. “No one really seems to care.”

It lists a fake birth date, a fake Chilean nationality and a fake name. For about the cost of admission to Disney World, he now had a bogus green card.

Before long, Jose landed work inside a Walmart, with a fictional identity. A friend’s roommate worked as a labor recruiter, specializing in rounding up crews of Venezuelans to rehab Walmart stores damaged by flooding and other natural disasters. When a job came up, the recruiter would spread the word on social media to her network of Venezuelan immigrants hungry for work.

In mid-August, she directed Jose and two Venezuelan friends north to a storm-damaged Walmart store in Salem, Massachusetts, according to WhatsApp messaging among the friends. “We didn’t even know where that was,” Jose said. “Near Boston?”

They arrived at the designated meeting spot, a Motel 6, where 20 people were already assembled. “Everyone, and I mean everyone, was Venezuelan,” he said. Another recruiter asked the workers for a name, any name, and a Social Security number, if they had one, Jose recalled. If they didn’t, no problem—just add a zero to your Venezuelan national ID number, she told them. That’s what Jose did.

The shift was 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. The pay: $10 an hour and $15 for overtime. For four days, Jose and his friends broke down shelves, discarded soggy ceiling panels, cleared damaged partitions, installed new ones and scrubbed floors.

The Walmart rehab was overseen by a Houston-based company called Cotton Holdings, which has a contract to perform disaster-recovery work for Walmart stores across the country. In written responses to questions about the job in Salem, Cotton said it uses subcontractors to provide labor at worksites, and those firms are responsible for their own hiring practices and payment methods.

“Cotton holds our partners to the highest professional and ethical standards,” the company said in an email. “Cotton has never knowingly hired undocumented workers and is not aware of any instance of Cotton or our subcontractors hiring undocumented workers. Furthermore, Cotton explicitly and contractually requires that its subcontractors provide only legally authorized workers for every client project.”

But Walmart spokesman Randy Hargrove said it is Cotton’s responsibility to ensure that anyone it places inside Walmart stores is legally authorized to work. And he said the retailer would start an inquiry. “Cotton Holdings has signed an agreement continually verifying that they, and their subcontractors, are in full compliance with immigration and employment laws,” he said in a statement. “If the report of undocumented workers is true, we will take immediate action.”

Cotton said it “takes this matter seriously and will investigate thoroughly any allegations regarding our subcontractors’ hiring practices on Cotton projects.” The company also said it would be misleading to suggest that one project “is representative of other Cotton projects or Cotton Holdings practices in general.”

Walmart has had immigration issues with other staffing companies. In 2003, immigration agents raided dozens of Walmart stores across the U.S., arresting more than 200 undocumented immigrants working as janitors. A wider Justice Department investigation found that Walmart’s janitorial services contractors were using such immigrants (many from Eastern Europe), supplied by labor subcontractors. According to court documents, an owner of one of the janitorial contractors told federal investigators that “high level” Walmart executives knew of the illegal employment practices, with one of them instructing the man to set up shell companies to conceal the behavior.

Two years later, Walmart paid $11 million in fines to the government to settle the investigation. The government said criminal charges against the company or its executives related to the investigation “would not be appropriate.” As part of the settlement, Walmart admitted it hadn’t done enough to ferret out the illegal hiring practices, but it stipulated that the company “did not have knowledge, at the time the independent contractors initially were hired,” about the scheme, according to the settlement documents.

Since then, Walmart started regular auditing of its contractors, and has created an internal immigration vetting system for them. It asks six relevant questions, including whether the contractor has filled out federal immigration paperwork or uses the E-Verify system, a web-based government service that compares information from prospective workers’ documents to existing federal records. Cotton passed that vetting. “We won’t tolerate suppliers using undocumented workers to service our facilities,” Hargrove said.

American businesses’ dependence on immigrant labor took root decades ago. When workers shipped overseas to fight in World War I, the U.S. government admitted large numbers of Mexicans to work untended farm fields. They were repatriated to Mexico when the Great Depression hit, but were called upon again during World War II. After the GIs came home looking for work, Congress made it a crime to “harbor, transport, or conceal” undocumented immigrants. But farmers in Texas, worried they’d lose a cheap labor source, won an exemption: Employers who hired undocumented workers couldn’t be held criminally liable. The loophole became known as the Texas Proviso.

In 1986, as the number of undocumented immigrants apprehended by the Border Patrol reached a record 1.7 million, Ronald Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act. It gave amnesty to nearly 3 million undocumented immigrants and created the first potential sanctions for employers.

But the business lobby won what was essentially a modernized version of the Texas Proviso: The government would have to show that companies had “knowingly” hired undocumented workers. Moreover, the act stipulated that if an employer views a worker’s document that “reasonably appears on its face to be genuine,” he or she has satisfied the law and could even be penalized for discrimination by rejecting it or asking for additional proof.

That led to a cottage industry of fake-document makers, said Muzaffar Chishti, an attorney at the Washington-based Migration Policy Institute. “It became a big loophole,” Chishti said. “Employers who had become used to hiring unauthorized workers told them, ‘Go and get me documents.’”

The law tasked government agents with enforcing its employment provisions—activity that the Trump administration has vowed to increase. In the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, federal officials reported opening 6,848 worksite investigations, quadruple the prior year’s total. In fiscal 2017, 1,730 employers were subjected to “enforcement-related actions” for hiring illegal workers, according to the latest figures from the Department of Homeland Security. According to an analysis by the Migration Policy Institute, that amounts to about .03 percent of employers.

When prosecutors target companies that use contract labor, it’s usually not top executives but underlings who suffer the consequences. That helps explain why Israel Arquimides Martinez is sitting in federal prison on a windswept swath of scrub land outside the West Texas town of Big Spring.

Martinez’s mother brought him to the U.S. from El Salvador when he was 13. After dropping out of high school, he got a green card and later a job driving a garbage truck for Waste Management Inc., the publicly traded Houston-based company that serves 20 million customers in the U.S. and Canada.

He says he worked hard, never had an accident, and soon rose to lead driver. He worked 12-hour shifts, Monday to Saturday, for $130 a day. “It was a good job, and I put everything I could into Waste Management,” said Martinez, a burly man with a crew cut and goatee. “That’s why it’s so hard to see why they blamed all this on me.” He’s sitting with his feet shackled in the visitors’ room of the Flightline Correctional Center, where he’s been an inmate since early 2017.

In April 2012, federal immigration agents raided a Waste Management garbage truck depot in Houston and arrested 16 undocumented workers. Two years later, a federal grand jury indicted Martinez and two Waste Management garbage-truck route managers for employing and harboring undocumented immigrants, a felony.

The indictment outlined how a company called Associated Marine & Industrial Staffing Inc., or AMI Staffing, which had a $20 million contract with Waste Management, supplied the garbage workers and encouraged undocumented immigrants to apply for jobs using false documents. Two AMI employees were also charged.

Martinez argued there was no way he—a low-level manager who barely speaks English and has no real financial stake in Waste Management—should be held responsible. He said AMI did all the hiring, and all the workers were approved by his supervisor, Ceasar Santiago-Arroyo, and other regional managers at Waste Management. “I refused to plead guilty to something I didn’t do,” said Martinez, 41.

He and another low-level Waste Management manager decided to go to trial. But Santiago-Arroyo—along with an AMI manager named Mary Louise Flores, who was in charge of hiring at the Waste Management site—pleaded guilty and testified against Martinez.

Flores told jurors that Martinez and his Waste Management co-conspirators came up with the idea to use previous employees’ documents for the new, undocumented workers. She described struggling to keep track of dozens of such cases and showed jurors a notebook containing her handwritten scrawls of all the workers and their assumed identities.

Santiago-Arroyo, Martinez’s supervisor, testified that he knew workers were undocumented but allowed the practice because of concern that Waste Management could lose its contract in Houston if it didn’t have enough labor. He also said he believed that at least two immediate supervisors, regional managers of Waste Management, knew about rampant use of undocumented workers.

In April 2016, a federal jury found Martinez and another low-level Waste Management manager and driver guilty of conspiracy to hire undocumented immigrants. Santiago-Arroyo was sentenced to 27 months in prison and Flores received probation. Martinez got seven years.

No other Waste Management employees were prosecuted. Santiago-Arroyo testified that investigators never asked him about his superiors at Waste management when they questioned him about the scheme. For violations tied to the case, Immigration and Customs Enforcement this year fined the company $5.5 million, a tiny fraction of its nearly $15 billion in annual revenue.

Waste Management blamed it all on Martinez and the other garbage men. “The three employees involved intentionally broke pre-existing immigration compliance rules, in clear disregard of company policies,” Tiffiany Moehring, communications manager at Waste Management, said in a statement. “Those employees were fired, and we terminated our relationship with the temporary staffing agency involved.”

Kent Schaffer, an attorney who represented Martinez on appeal, said he’s angry his client took the fall: “Upper management was allowed to skate on this case. The people who are the least culpable are going to prison.”

A couple of months ago, Martinez said, an ICE agent visited him in prison and asked him to sign a document agreeing to be deported once he serves his time. But his three children and his wife are American citizens or residents and don’t want to live in El Salvador. “They deport me, and I don’t know when I’ll see them,” he said.

With 1,800 stores and 350,000 employees, Target Corp. promotes itself as a national leader in corporate social responsibility and workers’ rights. But its cleaning contractor, Diversified, has drawn controversy.

When Diversified janitors who cleaned Target stores and other big-box retailers in Minnesota filed a lawsuit in 2011, they alleged violations of labor law, such as being required to work without breaks or overtime pay. They also detailed how they were instructed to clock in using the identifying information of former workers whose names remained in Diversified’s computer system.

The assumed identities were known by workers and managers as “ghost employees.” The workers described getting electronic pay cards in the name of someone else that they dubbed “ghost cards.” In a sworn statement filed in the lawsuit, Marco Alvarez, a former Diversified area manager in Minnesota, said hiring undocumented workers to clean Target stores was an “unwritten official policy” for the contractor in multiple states. “The action of hiring illegals was part of the scheme,” Alvarez said. Diversified was hiring people, “intentionally and knowingly, who did not have proper status so they could avoid paying overtime.”

Diversified denied any wrongdoing, and settled the suit in February 2013 for $675,000, according to an agreement filed in federal court. In court filings, the Tampa-based company acknowledged that “a fraudulent scam may have existed in the Minneapolis metro area,” but blamed it on some employees who acted “perhaps in concert with a rogue area manager.”

When Target then sought bids on a new contract for its Twin Cities stores, Diversified didn’t submit one. But Target kept the company on elsewhere. A Target spokesperson said the retailer had retained Diversified in the other locations because, at the time, it was unaware of any additional labor or immigration complaints about the firm. As of Dec. 1, Diversified’s janitors were cleaning 400 Target stores in 23 states. Its website also lists more than a dozen other major U.S. companies as customers.

An attorney for Diversified, Meredith Gaunce, said the firm doesn’t hire undocumented workers. “This has never been company practice,” Gaunce said, adding that its managers confirm applicants’ eligibility with the E-Verify system. “If an undocumented person did perform work, then clearly there was an intent to evade company rules and procedures.”

Martha Lopez said she began working for Diversified just days after arriving in Nashville from Los Angeles in December 2012. A friend told her about a job notice tacked to the bulletin board at their neighborhood Latino market. She called about it, and the woman who answered put her to work before dawn the next day, cleaning a Target store. The woman promised to pay her in cash, no questions asked, and handed her the pay card assigned to “M Hernandez Cleme,” Lopez said.

“They always told me that person had papers and had been in their system for many years,” said Lopez, 42. “So that’s how they could pay me.”

Gaunce, Diversified’s attorney, confirmed that the name on the pay card does indeed belong to a former employee, but said she had seen no evidence that any Diversified manager distributed ex-workers’ pay cards to current employees. She also said the company was unaware that Lopez is undocumented, and the firm has been unable to corroborate her claims of unpaid wages. Gaunce said the firm does have a record of employing Lopez, though it dates to late 2013, ending on Dec. 24 that year.

For her part, Lopez said she worked cleaning five different Targets in the Nashville area for Diversified over about five and a half years. She had four managers over that time, she said, and they all had her use the same pay card—until it stopped working early this year.

By the time her manager replaced the card weeks later—with one that said “DMS Employee”—Lopez said she’d racked up $3,708.75 in unpaid wages. In late August, she’d had enough. She was tired of the schedule—seven days a week with no overtime and no time for breaks, she said—so she quit.

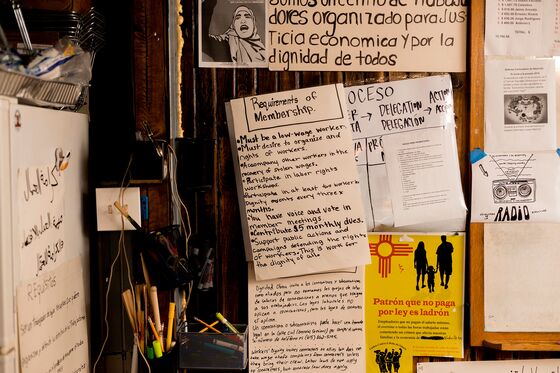

Eventually, Lopez met some people from an immigrant labor advocacy group called Dignidad Obrera, who worked out of a rundown house in Nashville. Staff members told her about two janitors, who last year also said they’d been shorted by Diversified—and successfully collected from the company. Like Lopez, the men said they were given pay cards with other people’s names on them. One was issued to a woman named Alma Hernandez; the other was in the name of Angel Amaro, the workers said. Both are names of former Diversified employees, Gaunce said.

On Aug. 17, 2017, Gaunce sent an e-mail agreeing to pay double the amounts the men were seeking, without disputing or admitting any of their allegations. The lawyer asked that in return the men stop their protests, the email shows. Gaunce told Bloomberg that the company’s internal investigations found no merit to the men’s complaints, but “we wanted to ensure nothing had been miscommunicated or had evaded our processes.”

Lopez was inspired by their success. She and another Mexican immigrant who had worked with her cleaning the Brentwood store reached out to Dignidad Obrera. While the group doesn’t inquire about workers’ immigration status, it helped her write a letter to Diversified, demanding double their back pay. On Sept. 19, Lopez received a letter from Gaunce asking for more documentation of her work for Diversified because the firm’s records indicated she hadn’t been active in the payroll system for more than four years. “I hope you can understand our confusion,” read her letter.

With nowhere left to turn, Lopez took her grievance to Target’s front door. On that October morning, she and three fellow members of Dignidad Obrera gathered beside the white customer service desk in the Brentwood Target to give their complaint letter to a manager and ask for help.

When the store manager walked up, Lopez was hopeful. The woman had greeted Lopez most mornings and never complained about her work. But when she didn’t say hello and refused to even accept the letter, Lopez was taken aback. “You guys work through Diversified,” the manager said, according to a video of the encounter. “We, unfortunately, don’t have any ability to do anything directly for you.”

After Bloomberg asked about Lopez’s allegations, Target met earlier this month with Diversified’s chief executive officer, Derek Gordon. According to a Target executive familiar with the meeting, Gordon pledged to investigate and address the issues raised.

Target spokeswoman Jenna Reck said the retailer is “firmly committed to responsible business conduct and we hold our team, business partners and vendors to the highest standards. We require our vendors to follow all applicable laws and regulations for their business, including laws around wages, overtime, worker documentation and more.”

A few days after the meeting with Gordon, Target said it would cancel Diversified's contract in Tennessee. It also said that because of the allegations it would order a more extensive look into all of the contractor's work for Target, as part of a scheduled annual audit. The auditor’s findings “will inform the next steps for our national contract with Diversified” in 22 other states, Reck said.

For its part, Diversified said in a statement that it has always performed well in Target's annual audits and will cooperate with this one: “We appreciate their concern for their brand in light of these unwarranted claims.” As for Lopez’s allegations, Diversified said she and the worker's group hadn't provided sufficient proof of her claims, but the firm paid her anyway.

A check in the amount she’d demanded arrived this week—in her real name. For the first time in years, she was no longer a ghost.

—With assistance from Jonathan Levin and Nathan Crooks

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Flynn McRoberts at fmcroberts1@bloomberg.net, John Voskuhl

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.