Johnson’s Popularity Faces Key Test in a Brexit Heartland

Johnson’s Popularity Faces Key Test in a Brexit Heartland

(Bloomberg) -- The town of Hartlepool in northeast England is the kind of place a Conservative prime minister would ordinarily struggle to find support.

One of the most deprived areas of the U.K., the blue-collar port saw its steel industry collapse in the 1970s and 80s and the unemployment rate remains among the highest in the country. Politically, it’s backed the Labour Party at every U.K. election for almost half a century. But then came Brexit.

Hartlepool holds a vote on May 6 that will be a critical test for Prime Minister Boris Johnson after his landslide victory in 2019 paved the way to take Britain out of the European Union after years of wrangling.

It will be a key indicator of whether Johnson’s initial popularity has survived a pandemic that left Britain with the worst death toll in Europe, and whether Brexit supporters still buy into his promise to “level up” the economy. And now there’s also the question of any damage from a recent scandal over Johnson’s conduct in office that’s engulfed his government. He has suffered a relentless barrage of negative headlines even from usually supportive newspapers.

The Conservatives are the bookmakers’ favorite to win the election for the town’s next parliamentarian. Polls from Survation and Ipsos MORI have also put the party in front. That’s mainly as votes from the now defunct Brexit Party at the last election are expected to transfer to Johnson in a Labour northern heartland where a Tory win would have been unthinkable a few years ago. The town backed leaving the EU by a thumping 70%.

One such voter is Geoff Carr, who runs a shoe repair business next to a closed-down pawnbroker on Hartlepool’s main shopping thoroughfare. A committed Brexit supporter, Carr says the U.K.’s Covid-19 inoculation program that’s covered more than half the population vindicates leaving the EU. He will now be voting Conservative.

“The vaccine, you can’t fault them for that,” said Carr, 58, in between polishing shoes and serving customers behind a large Perspex screen. “That’s one of the reasons we got out of Europe, so we can make our own decisions.”

Hartlepool epitomizes Britain’s post-industrial decline, a forgotten coastal town that’s often more known in Britain for a folklore tale about locals hanging a monkey suspected of being a French spy during the Napoleonic Wars. (The town elected its soccer club’s monkey mascot as mayor in 2002 and he successfully went on to win two more terms.) Many storefronts are boarded up, locals complained the town’s center has been neglected while investment went into its marina.

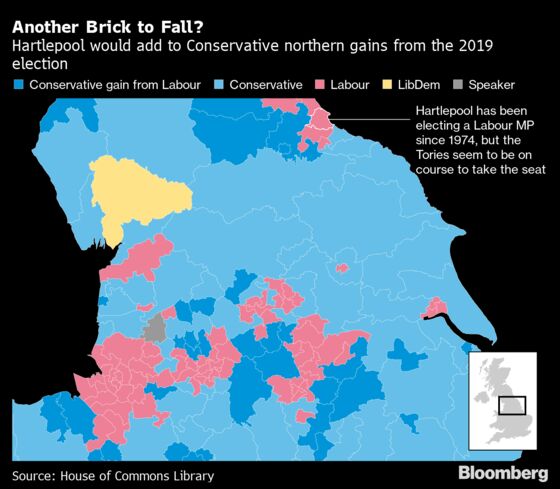

A victory would reinforce Johnson’s position in what used to be called the “red wall” of Labour-voting districts across England’s north. At the last U.K. election, neighboring Brexit-backing areas such as former mining town Bishop Auckland and Redcar, where a giant steelworks lies defunct on the North Sea coast, defected to the Tories for the first time in decades.

The by-election is also just one of the tests facing Johnson on May 6. There are also elections to the Scottish Parliament, where the nationalists look on course for an emphatic win to ramp up pressure for another independence referendum, the Welsh assembly and across English municipalities.

“There’s always quite a lot at stake in these kinds of elections, but perhaps the stakes are higher this time around than they’ve been for a few years,” said Tim Bale, professor of politics at Queen Mary University of London. “The sheer number of contests taking place means it’s a kind of Super Thursday, almost equivalent to the U.S. mid-term elections.”

Voters will be making their choice as Johnson battles on a number of fronts. First there were incendiary claims made against him by former adviser Dominic Cummings, who questioned his competence and integrity in a lengthy blog post. Then the Electoral Commission said on April 28 it would investigate whether the prime minister appropriately declared any donations that funded the refurbishment of his Downing Street residence.

The Labour Party has sought to capitalize on the issue, branding the Tories as a party of “sleaze,” an echo from the 1990s when scandals helped undermine the government and propel Tony Blair into office.

But on the streets of Hartlepool voters were either unaware of the controversy or unmoved by it. “There are far more important things going on than who’s got their hands in the till at 10 Downing Street,” said Peter Davison, 66, a retired businessman. “People don’t care in the slightest.”

A bigger challenge may be apathy. A life-long Labour voter, Davison won’t be voting because he is disillusioned by politics and it’s not hard to find similar views toward the politics going on 230 miles (370 kilometers) south in London.

The majority of people approached on a recent weekday to talk about the election said they weren’t interested in it and didn’t know anything about it. Ale Issmat, a local barber, said he would be voting for the Conservatives, but only because their campaign had brought some customers to his salon.

Yet much is at stake for Hartlepool. Like for similar regions, the Brexit vote was a cry for change, to end years of perceived neglect by the government at Westminster following the collapse of manufacturing industries. Johnson’s post-Brexit mantra is to better distribute wealth and opportunity across the U.K. For its part, Hartlepool has been refocusing its port activity on green energy in recent years.

The May 6 vote, along with those across the U.K., is also the first real test of Labour leader Keir Starmer’s ability to reignite the party’s fortunes after a catastrophic result in 2019. Starmer’s standing with voters has lagged in recent weeks as Johnson has ridden a wave of good feeling following the country’s successful vaccine roll-out. If Labour isn’t making significant gains, it’s going to be hard to imagine the party will be back in power at the next U.K. election, said Bale, the politics professor.

Labour loyalties, at least, still run deep in the north of England, and for many voters the idea of voting Conservative remains anathema.

Evelynne Ray, 72, a retired nurse, blamed the Tories for cuts to local council funding, which she said led to the closure of hospital services. She also blamed Johnson for not locking the country down sooner at the start of the pandemic. If he’d acted more decisively, social restrictions could’ve been lifted months ago, she said.

“I’m definitely not a fan of Boris,” Ray said, a disposable face mask tucked under her chin and sitting opposite Hartlepool’s war memorial. “I just don’t like him at all.”

Yet with coronavirus restrictions being lifted and more than twice the proportion of the population vaccinated compared with the EU, Johnson has gained some political capital.

Nibbling on shortbread and drinking coffee outdoors at a cafe, Barbara and Brian Tunstall expressed sympathy for the prime minister, particularly in light of claims made against him by Cummings, his former chief adviser. “It makes me think a lot worse of Cummings than Johnson,” Brian, 77, said. “I feel sorry for him,” Barbara said. “He’s had a hard old year.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.