So Much Gas, So Few Allies Spells Trouble in Populist Nation

So Much Gas, So Few Allies Spells Trouble in Populist Nation

(Bloomberg) -- South America’s only successful populist government has triumphed largely thanks to the natural gas it exports to its neighbors. But that may soon be changing.

Contracts with Bolivia’s biggest customers -- Brazil and Argentina -- are in the process of being renegotiated at a time when both are vowing to boost their own output, and enjoy extensive coastlines that allow them access to a growing global market for liquefied natural gas.

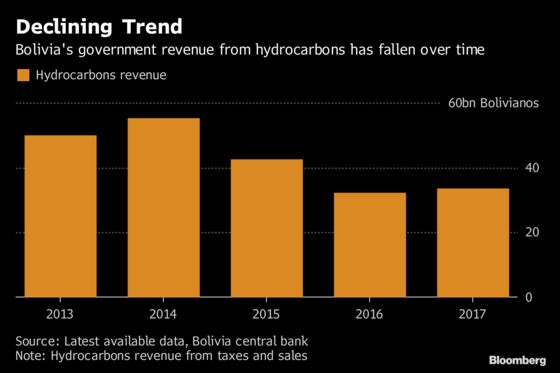

The upheaval comes as Bolivia’s public debt hits record levels, and an October election is bearing down on President Evo Morales, the longest-serving leader in South America. Morales has posted twelve years of economic growth, surviving a global financial crisis and a commodities downturn. Now he’s facing a new test, with revenue from hydrocarbons in decline and popular protests soaring.

"Basically, there’s a new game in town that has broken the Bolivian monopoly on natural gas in South America," said Fernando Valle, an oil and gas analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. "When you have super high margins somewhere, someone is eventually going to find a way to go into that market and undercut you. That’s what’s happening to the Bolivians now."

Over the last four years, it’s become increasingly cheaper to build floating terminals that can receive huge LNG tankers, store the gas and vaporize it for in-land power generation. Meanwhile, YPF SA, Argentina’s state-controlled energy company, is now planning to build an export terminal that will allow it to liquefy the country’s gas and ship it out.

In 2018, Bolivia’s gas exports fell by about 30 percent, drastically impacting the government’s revenue and the entrance of foreign currency, according to Alvaro Rios, a founding partner of Gas Energy LA, a Bolivia-based consulting firm. Public debt, meanwhile, soared to 51 percent of gross domestic product in 2017, according to the latest available data from Bolivia’s central bank. That’s up from 36 percent in 2014. Morales’ popularity is declining, with his approval rating falling six points in one year, to 43 percent, according the latest Ipsos poll in August.

“The government is losing popularity because the loyalty from many local leaders is more economic than political,” said Waldo Albarracin, the dean at Universidad Mayor de San Andres, and a member of the National Council in Defense of Democracy, an opposition group.

Bolivia’s Hydrocarbons Ministry, meanwhile, declined to comment for this article.

Last Standing Member

Morales is the last standing member of the so-called Pink Tide, a generation of left-wing South American leaders who rose to power promising social change. Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, Argentina’s Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, Brazil’s Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa are all gone. And Morales’s last ally, Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro, is locked in a standoff over who is the legitimate authority in that economically-ravaged country.

A new generation of leaders is in place with very different political philosophies. Both Jair Bolsonaro, the newly elected right-wing president of Brazil, and Mauricio Macri, the leader of Argentina, have promised to make their countries increasingly energy self-sufficient moving forward.

When Brazil signed its contract with Bolivia in 1999 and Argentina signed its deal in 2006, gas was a scarce and expensive fuel mainly due to the difficulties of storing and transporting it. Bolivia was able to get around these issues by having two pipelines built that directly linked the land-locked nation with its neighboring countries.

Argentina’s Vaca Muerta

Today, Argentina’s Vaca Muerta boasts the world’s second-largest shale gas reserves after China. In December, Argentina’s production reached 28 million cubic meters a day, more than three times higher than at the same stage in 2017, according to the nation’s Energy Secretariat. Brazil’s gas production is up as well, with the average monthly output rising 1.7 percent in 2018 from the previous year’s average, according to the latest available data from November.

In October, Argentine former Energy Minister Javier Iguacel said that the country won’t need Bolivian gas by 2020, and Brazil is now working to negotiate a new deal.

Brazil now spends about $1.3 billion a year on Bolivian gas. Former President Michel Temer’s administration was considering reducing the current contract by half, and Petrobras executives under Bolsonaro’s government have said that a deal contemplating smaller volumes will allow other companies beyond Petroleo Brasileiro SA, the state-controlled energy giant, to import gas from Bolivia directly.

Contract Expiring

While the contract with Bolivia is set to expire in December, a key provision mandates that Petrobras pay for at least 24 million cubic meters per day. Bolivia’s state-owned gas company YPFB says the contract will span beyond December because it hasn’t delivered all the gas that Brazil has paid for and is hopeful that the contract will be extended through 2023.

In January, Bolivian officials approached Peruvian authorities in what’s seen as an attempt to secure gas exporting deals elsewhere. But any significant agreement would require first to build a pipeline to transport the gas. The chances of this happening in the near term are close to zero, Valle said, because it would involve a large investment and the signing of bilateral agreements.

“The Bolivians are obviously trying to find options to have a stronger negotiating position, but the reality is that they’re going to have to lower their prices,” Valle said. “The political situation plays a lot into this; Morales realizes that he is in a weaker position now.”

Fourth Term

In October, Morales will be seeking a fourth term as president. In 2017, the country’s Constitutional Court threw out term limits in Bolivia that would have kept Morales from running again. The move spurred widespread protests.

The election will be "an inflection point for Evo Morales’ presidency, for his legacy and for the country," said Tanvir Malik, a Bolivia analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit. "Until now, Morales has been able to spend his way out of any significant opposition coming up against him. But the same protests will be harder to quell now."

To contact the reporters on this story: Laura Millan Lombrana in Santiago at lmillan4@bloomberg.net;Jonathan Gilbert in Buenos Aires at jgilbert63@bloomberg.net;Sabrina Valle in Rio de Janeiro at svalle@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Luzi Ann Javier at ljavier@bloomberg.net, Reg Gale, Will Wade

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.