Empty Hair Salons Can’t Be Saved by a Central Bank

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The pachinko parlor is abandoned and there isn’t much Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda can do about it.

The gambling hall near the rail station in Naie, a town of roughly 5,000 on Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido, is now a rusted hulk. This community, like many in provincial Japan, has been ravaged by the country's shrinking and aging population. These challenges spill into all aspects of commercial and social life in the countryside, yet they can seem distant to the mobile-phone tapping professionals in the crowded streets of Tokyo and Osaka.

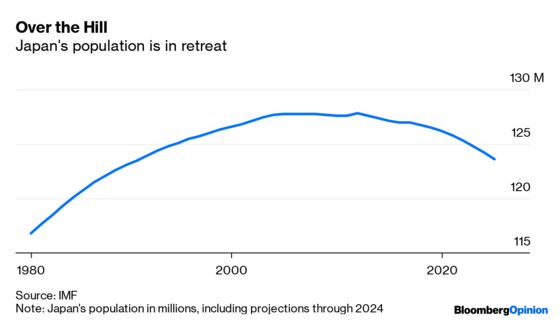

It’s towns like Naie that illustrate the scope of what Japan’s monetary policymakers need to accomplish, and offer a cautionary tale for global central banks from China to Europe facing similar demographic struggles. Last week, the European Central Bank doubled down on negative rates and the Federal Reserve is likely to cut rates again this month. Many observers predict the BOJ will do more to try and spur the economy. Recent interviews with businesses, consumers and officials in Hokkaido, however, suggest the central bank is ill-equipped to deal with the problems at the heart of the Japanese economy.

Fiscal policy hasn’t been much more promising. The Cabinet Office's Economy Watchers Survey published last week showed the outlook among Japan's restaurant managers, taxi drivers and shopkeepers fell to a five-year low in August, mostly attributed to the imminent hike in the nation's consumption tax. That's despite government exemptions and pledges to pour money into education and childcare.

In that light, it's perhaps unsurprising that BOJ deliberations seem incidental to the lives of the people I met in their homes and workplaces, where phrases like “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing With Yield Curve Control” drew blank stares. What they do know of Japan's massive stimulus is that it's producing little benefit; and some prescriptions – such as negative interest rates – have even hurt.

“I don't directly associate my difficulties with the Bank of Japan,'' said Ryoko Hokao, the owner of the Pearl beauty salon in Yubari, the first municipality in the country to file for bankruptcy. “I have no expectations that the national or even Hokkaido governments will do anything for me.”

Hokao had just two customers in September, and was expecting a third the following day. To make ends meet, she does menial tasks in a nearby aged-care facility. Her husband requires dialysis treatment for a kidney illness, which he can no longer get in Yubari because the clinic had to close, she explained over coffee and sweet potatoes.

Up the road is a noodle shop that’s been in Shinichiro Takahashi’s family for almost a century. He says employees from the town's two banks come to his family's restaurant pitching for business. “There is cheap money available, but local businesses have no reason to go to the banks because there is no demand.”

Enjoying a cigarette as lunch hour drew to a close, the octogenarian reminisced about how vibrant the area was when he was young. The town’s population has declined to about 8,000 from roughly 120,000 in the 1960s, according to the local chamber of commerce. The closure of Yubari's coal mines was a blow the community never recovered from; population decline only made matters worse.

The BOJ is powerless to improve either trend. Steps like increasing the holdings of exchange-traded funds and real-estate investment trusts do little for residents of Naie and Yubari. Hokao, the hairdresser, is worried about growing income inequality.

Perversely, policymakers do have the ability to make things worse. Negative interest rates have hit regional lenders particularly hard, given their historical dependence on smaller cities and rural precincts where the population is aging most rapidly. The danger is that in an effort to survive, provincial banks chase riskier business.

You could argue that Japan's overall economy may have experienced an even deeper funk without the the BOJ's innovation. (It was the first major central bank to undertake quantitative easing.) Gross domestic product has expanded for much of the past four years, and at least policymakers have staved off outright deflation.

That isn't good enough for business owners like Yuuji Ohta, president of Ohtaseiki Co., which makes makes molds used in the auto and aviation industries, as well as robots. His firm is about a 20-minute walk from Naie’s defunct pachinko parlor, past the disused homes, abandoned candy stores and a kimono shop that’s seen better days. Negative interest rates have made regional lenders very conservative, he says.

“I can’t go to the BOJ for a better robot,” he said. “Nor can it repopulate Japan.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.