Big Pharma Faces the Curse of the Billion-Dollar Blockbuster

Today’s extraordinarily profitable drugs have investors demanding massive followups.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The biggest pharmaceutical companies count on multibillion-dollar drugs to fund their expensive research units and justify high share prices. But now investors want more, demanding that companies queue up the next crop of top products before the current generation even hits peak profitability.

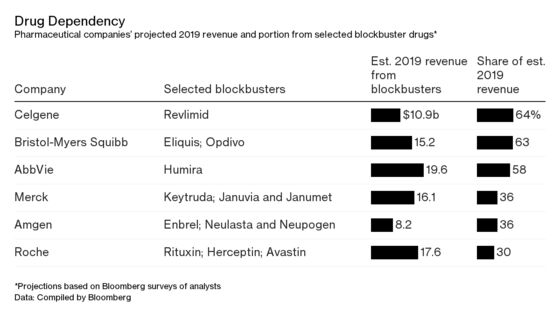

This conundrum is at the heart of the industry’s biggest merger deal. Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. on Jan. 3 agreed to pay $74 billion in cash and stock for Celgene Corp., a New Jersey biotech that gets almost two-thirds of its revenue from a single medicine: the blood cancer pill Revlimid, the third-biggest-selling drug in the world, with almost $11 billion in revenue expected this year, according to analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg.

Seen one way, Bristol-Myers got a bargain. Investors had already punished Celgene for the lack of a successor to Revlimid, driving down the biotech’s share price almost 40 percent last year. That certainly made the acquisition cheaper. Bristol-Myers insists that its prize will eventually deliver valuable new products. But the market’s worries about Celgene’s product pipeline immediately shifted to its buyer—even though the cancer drug is expected to continue raking in tens of billions of dollars over the three years until cheaper copies emerge. “They need blockbusters. It’s a perpetual chase,” says Ketan Patel, a fund manager at Edentree Investment Management Inc. in London. “The assumption is that every year you’re going to find a fantastic product; it doesn’t work like that.”

The prospect of big drugs going off patent—allowing rivals to market their own versions of a popular medicine at a lower price—causes chronic anxiety in the industry. Japan’s Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., which recently bought Shire for $62 billion, has been trying to refill its pipeline since at least 2012, when its top drug, Actos, lost patent protection.

Almost a decade ago, Pfizer Inc. bought rival Wyeth for $68 billion in part to soften the blow from patent expiration on Lipitor, then the world’s top-selling medicine. The cholesterol treatment was among the casualties in a three-year patent bloodbath from about 2010 to 2013, when several top-selling drugs began losing protection, including Pfizer’s Viagra erectile dysfunction medicine, Eli Lilly’s Cymbalta for pain, and Merck’s blood pressure drugs, Cozaar and Hyzaar.

Pharma investors were left gun-shy, says Daniel Mahony, a Polar Capital fund manager, given the lengthy period it often took traditional drugs to gain sales momentum. Many older blockbusters were “like supertankers; it takes a long time to hit a billion dollars,” he says. “And then, you know, the patent expires, and it’s gone.”

Shifting their focus over the past two decades toward complex specialty medicines, such as high-tech drugs made from cells and aimed at highly targeted groups of patients with difficult-to-treat ailments, was supposed to help pharma companies fix that problem. The new drugs—which can cost more than $100,000 a year per patient—would be harder to copy than chemical-based medicines, the reasoning went, and could rule smaller market segments without facing competition from a range of me-too compounds.

The strategy yielded a new generation of drugs for cancer and auto-immune diseases that became the industry’s next massive moneymakers, each selling in excess of $5 billion annually. AbbVie Inc.’s Humira, a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis that’s the world’s No. 1 drug, is predicted to rake in about $20 billion annually until it begins facing U.S. competition in 2023.

Still, the industry’s rush toward biologic compounds has opened companies up to a range of other risks, Mahony says. A specialized cancer drug that patients and insurers adopt quickly “can get to peak sales in maybe two years,” he says, “which is great if you’re a hedge fund, pretty crappy if you’re a long-term investor who’d like steady growth.”

The accelerating rate of innovation has also created a new danger: the possibility that, say, a biotech’s once-promising kidney cancer treatment may be overtaken by an even better one, causing the promising medicine’s sales to drop long before its patent expires, Mahony says. That’s led investors to begin scrutinizing the experimental medicines in drug companies’ pipeline at earlier stages than before, searching for signs that even the most successful pharma giants will be able to strike gold multiple times. Bristol-Myers was already struggling under the scrutiny. The company gets more than half its sales from a pair of drugs. One, Opdivo, was seen as a contender for dominance in the oncology market, but ceded ground in some areas to Merck & Co.’s immune therapy Keytruda. And as Bristol-Myer’s experimental drugs failed patient trial after patient trial in recent years, some investors suggested that the huge company might itself become a takeover target.

Celgene looked close to resolving some of its blockbuster problems with a treatment for Crohn’s disease called mongersen. Acquired from Irish drugmaker Nogra Pharma Ltd. in 2014 for $710 million, the drug was making good progress through human testing. But it failed in patient trials, and the company’s stock began its decline as investors brushed aside Revlimid’s healthy sales and punished Celgene for its dim growth prospects. The failure “was a catalyst for people to start thinking, Oh crap, what’s the actual total value of this company,” says Mahony, who owned Celgene shares at the time. “People looked at the company with a different set of eyes.”

Celgene made its own attempt at transformative dealmaking. Last year the company paid $9 billion for Juno Therapeutics, one of the leaders in the risky but potentially lucrative field of CAR-T therapy, in which a patient’s own immune cells are trained to zero in on and kill tumor cells.

Yet, when drugmakers need to replace $10 billion in revenue, one small deal or partnership won’t be enough to make up the difference, says Sam Fazeli, an analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence. So if Bristol-Myers completes the Celgene deal, it will face the necessity for even more—albeit smaller—deals to build up the pipeline post-Revlimid, he says.

Analysts have already started demanding that Merck—which has the world’s hottest new cancer drug in Keytruda—begin thinking about how to replace the $10 billion-a-year medicine when it loses patent protection a decade from now.

AbbVie is doing the same math. Chief Executive Officer Richard Gonzalez said last year he would consider a “bolt-on” acquisition deal as big as $20 billion to $30 billion—comments he later sought to moderate, saying the company hadn’t yet found the right asset. But the blockbuster dilemma is plain to see, according to Edentree’s Patel. “At some point sales are going to taper off,” he says. “That’s the danger of being overreliant on one drug.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.