Big Ocean Polluters Are Raising Rates to Offload Clean Fuel Cost

Container-shipping firms are managing to pass higher costs onto customers after switching fuel to meet environmental regulations.

(Bloomberg) -- Container-shipping companies, some of the biggest polluters of the world’s oceans, are managing to pass higher costs onto customers after switching to more expensive fuel to meet new environmental regulations that came into effect this year.

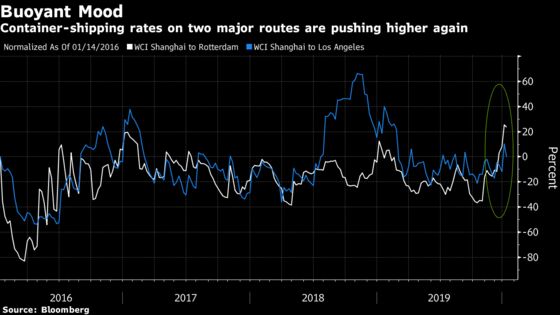

Shipping rates on major routes have jumped 31% since the end of November, helping to dismiss fears that costlier fuel would pile more pain on an industry already hurt by the U.S.-China tariff war. There are signs that dispute is now easing and the stuttering economy is picking up: China’s exports grew a better-than-expected 7.6% in December, the first year-on-year increase since July, while imports were also well ahead of forecasts, rising 16.3%.

“This year could be a turning point,” said Um Kyung-a, an analyst with Shinyoung Securities Co. in Seoul. “The new emissions regulation has given cause for container shipping companies to raise rates. Some shipping lines appear to have already started.”

A consolidation in the industry has also given shipping giants more sway on rates. Cosco Shipping Holdings Co. acquired Orient Overseas International Ltd. and A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S bought Hamburg Sud, while Hanjin Shipping Co. went bankrupt in 2016.

“The industry is now bearing the fruits of the consolidation,” said Rahul Kapoor, head of commodity analytics and research at IHS Markit Asia Pte Ltd. in Singapore. “With five carriers controlling close to 70% of the market, it becomes easier to pass along the cost. We have been seeing very strong capacity discipline by the carriers this year.”

Fuel is the biggest cost for shipping companies. From Jan. 1, the International Maritime Organization required that they use fuel with sulfur content cut to 0.5% from a 3.5% limit in most parts of the world previously. Ships can use higher sulfur fuel if they install cleaning devices called scrubbers, though more regions are banning the use of open-loop scrubbers that discharge sulfur back into the water. In November, Malaysia banned the practice within 12 nautical miles of its shores, following others like Singapore and China.

While major ports such as Singapore and Shanghai are well prepared for the new regulations and will most strictly enforce the rules, fuel availability remains a concern, according to Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Lee Klaskow. He said the use of floating storage for fuel -- in tankers off the coast -- has risen significantly, helping to also lift tanker rates.

At the end of last year, a total of 3,028 vessels including 551 container ships had scrubbers, mostly open-loop, according to BloombergNEF. There are more than 30,000 ships operating worldwide, of which over 5,000 are container ships, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

IHS’s Kapoor said non-conforming shipping companies could face a backlash from financial institutions that have already imposed higher fees on those not buying more fuel-efficient vessels. Companies that fail to meet fresh criteria will either face higher interest costs or fail to secure loans, he said.

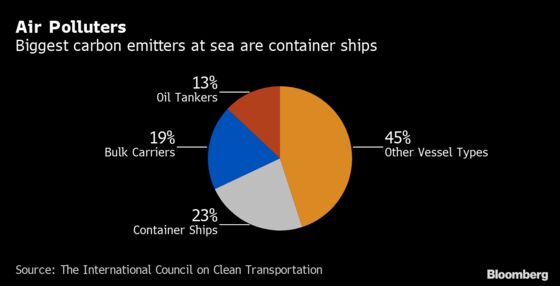

Shipping would rank as the sixth-biggest greenhouse gas emitter if it was a country, according to the World Bank, and if left unchecked could account for 15% of global carbon emissions by 2050. Envoys from 173 countries agreed at a 2018 meeting in London to limit emissions from the industry for the first time, with the aim of cutting them by at least 50% by 2050 from 2008 levels.

The World Bank says international maritime transport accounts for about 80% of global trade volume and 70% of its value. Charges on the spot market to haul 40-foot containers to Los Angeles from Shanghai have risen 22% in less than two months, according to latest available World Container Index data. Those to Rotterdam surged 38%. It typically takes about 20 days for goods made in China to reach the east coast of the U.S. and some 30 days to Europe.

Rates may wane after Chinese New Year in late January, Andrew Lee, an analyst at Jefferies in Hong Kong, wrote in a December note. Chinese exporters tend to increase shipments of toys, sneakers and other products before the holiday as factories across the country close for as long as two weeks.

Shipbuilders such as Hyundai Heavy Industries Co. and Samsung Heavy Industries Co. should benefit from the new rules too as companies replace older fuel-inefficient ships, said Park Moo-hyun, an analyst at Hana Financial Investment Co. in Seoul. Orders for new vessels slowed last year as many firms weren’t willing to invest ahead of the IMO regulations, he said. Hyundai Heavy, the world’s biggest shipbuilder, received $5.94 billion worth of new orders in 2019, down 14% from the previous year.

“The shipping industry is off to a good start in the new year,” Shinyoung’s Um said. “This could last into the year if they continue show discipline in their capacity management.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Kyunghee Park in Singapore at kpark3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Young-Sam Cho at ycho2@bloomberg.net, Will Davies, Ville Heiskanen

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.