Beef Industry Battles to Scrub Polluter Image as Vegan Burgers Boom

Studies have piled on exhorting people to eat less beef for environmental and health reasons for more than a decade.

(Bloomberg) -- The American beef industry, wary of the vegan-burger craze that’s sweeping the nation, is trying to scrub its image as a greenhouse-gas-emitting machine.

With big retailers and investors pressing companies to improve their footprints, giants like Tyson Foods Inc. and Cargill Inc. are promising ambitious reductions in emissions, including in supply chains. Chief sustainability officers are popping up all over meat C-suites, and social media ads are touting beef’s misunderstood health benefits.

It’s an uphill battle. For more than a decade, studies have piled on exhorting people to eat less beef for environmental and health reasons. By some measures, agriculture accounts for more global greenhouse gas emissions than transport, thanks in part to livestock production.

Meanwhile, plant alternatives have captured the zeitgeist as more Americans dub themselves flexitarians -- people who regularly substitute other foods for meat. Companies like Beyond Meat Inc., which saw its shares more than triple since its blistering initial public offering, are riding the anti-meat wave, extolling the virtues of vegan products that are showing up on menus of nationwide chains including TGI Fridays.

The rise of meat alternatives could start cutting into beef’s livelihood, if the recent decline of milk is any lesson. In less than a decade, alternatives came out of nowhere to steal significant market share from conventional cow’s milk, a shift that contributed to the bankruptcy filing this month of behemoth Dean Foods Co. Today, milk alternatives account for 13% of the market.

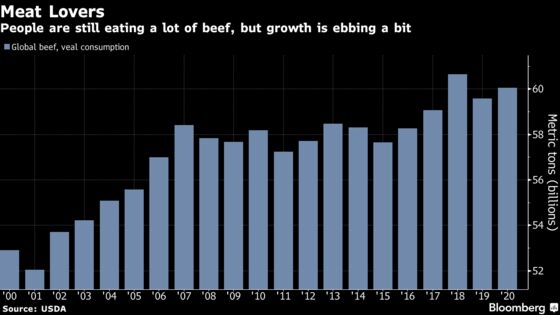

Still, beef consumption is robust in North America, and meat-eating in general is gaining globally. But the concerns come over how quickly vegan offerings are growing and the rise of the multi-trillion market for green and sustainable assets. Deborah Perkins, global head of food and agribusiness at ING Wholesale Banking, says the industry will have to keep on working to improve its footprint.

“It’s not like at any point will the industry be able to say: ‘We are done,’” she said. “People are going to want to eat meat. We will see growth in the alternative-meat industry, but I don’t think it’s going to completely replace meat.”

Much of the environmental woes come down to how the animals process food. Cattle emit methane, a particularly potent greenhouse gas, as part of their normal digestive processes. To put it simply, it’s cow farts, burps and manure that are a large culprit.

But the industry is pointing to new numbers that show how efficient American production is compared with the rest of the world. A recent government study funded by the industry pinpointed U.S. beef’s footprint at about 3% of man-made greenhouse gases, paltry compared with the 14.5% global number that’s often cited.

“We should own that 3% and reduce it, because 3% is still important,” said Kim Stackhouse-Lawson, director of sustainability at JBS USA. Brazilian parent company JBS SA is the world’s biggest beef producer.

JBS’s U.S. and Canada business units set a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20% by 2020 from a 2015 baseline.

The industry is also working to highlight the environmental benefits to raising cattle. The U.S. Great Plains, the heart of beef production and a major carbon sink, is preserved in part because of cattle grazing, said Nancy Labbe, who manages the World Wildlife Fund’s sustainable ranching initiative and also works with the U.S. Roundtable for Sustainable Beef.

Ruminants like cattle, because of their two stomachs, can digest feed inedible to humans, turning it into protein for human consumption. At Cactus Feeders, a company that operates feedlots in the Texas panhandle and turns over about a million head of cattle a year, 40% of what animals eat are byproducts from other industries. That includes glycerin, corn stalks, wheat straw, cotton burrs, distiller grains from ethanol production.

Technology can also help lower emissions. U.S. cattle have changed in recent decades through breeding and updates to feed formulas. Ranchers are able to produce the same amount of beef as they did in 1975 with 36% fewer animals, according to Sara Place, senior director of sustainable beef production for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Ermias Kebreab, a professor of animal science at University of California-Davis, said that major reductions in emissions are achievable over the next five years given the promise of imminent feed additives that reduce the amount of methane cattle produce.

One big challenge for the companies is to get ranchers on board. The meat industry isn’t vertically integrated, meaning the meatpackers don’t own the production assets (farms and cows).

Helping in the adoption of regenerative farming practices such as grazing management and cover cropping can make a difference, said Heather Tansey, sustainability director at Cargill’s animal-nutrition unit. The company has a goal of reducing emissions by 30% in its North America beef supply-chain from a 2017 baseline.

Tyson is trying to get its beef suppliers on board with its sustainability track, too. It has pledged a 30% reduction across its entire business inclusive of supply chains by 2030.

The company licensed a voluntary program called Progressive Beef, which audits and certifies best practices, including sustainability measures like water usage and manure management, said Justin Ransom, senior director of sustainable food policy.

To be sure, it’s important to keep a close eye on the commitments from companies and make sure they’re being realized, said Marcia DeLonge, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“It’s really important to keep the big picture in mind about how farmers and ranchers need to be part of the climate change solution,” she said.

--With assistance from Andrew Martin and James Attwood.

To contact the reporters on this story: Lydia Mulvany in Chicago at lmulvany2@bloomberg.net;Isis Almeida in Chicago at ialmeida3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: James Attwood at jattwood3@bloomberg.net, Millie Munshi, Patrick McKiernan

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.