To Save the New York Subway, Send in the Crowds

To Save the New York Subway, Send in the Crowds

(Bloomberg) -- For New York City subway riders, each trip is its own odyssey. Especially in the pandemic, there’s the rush to the station, the tense wait on the platform. The quest for a seat, always a delicate matter, is made more so by the need to socially distance. Straphangers must endure panhandlers and the fear of being confined underground if there’s a delay. Upon arriving at their appointed station, is it any wonder they dash for the street?

The last thing riders want to encounter is someone standing in their path, seeking their attention. So the eyes of travelers who’ve just stepped off trains widen with apprehension when they come upon Sarah Feinberg standing in the middle of a dank corridor in downtown Brooklyn’s busy Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center station. The interim president of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s subway and bus division waves at them. “Hi,” she shouts. “Anybody want a mask?”

Most riders on this January afternoon are already obeying the MTA’s rule to cover their face. Some race by Feinberg, pointing indignantly at their mask as if to say, “Can’t you see I’m already wearing one?” A good number, however, cluster around the subway chief, seeking as many extras as they can get on the MTA’s monthly mask distribution day. Only occasionally does she encounter a shirker—the gentleman who swaggers past her and rifles through a nearby trash can, the teenager who snatches a mask and sprints upstairs to the train platform without donning it. “You need to wear it!” Feinberg calls after her.

The MTA says 98% of its subway riders are masked. It’s an impressive achievement, one Feinberg often cites in her campaign to convince people that the largest public transit system in North America is safe. She says it’s rarely been cleaner, thanks to the MTA’s decision last April to close the 24-hour-a-day system, initially for four hours nightly and then just two, so it can disinfect its 6,455 cars. She boasts that the subway’s ventilation system replenishes the air on trains more than the six times an hour that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls for in many health-care facilities. “We’re three times better than that,” she says.

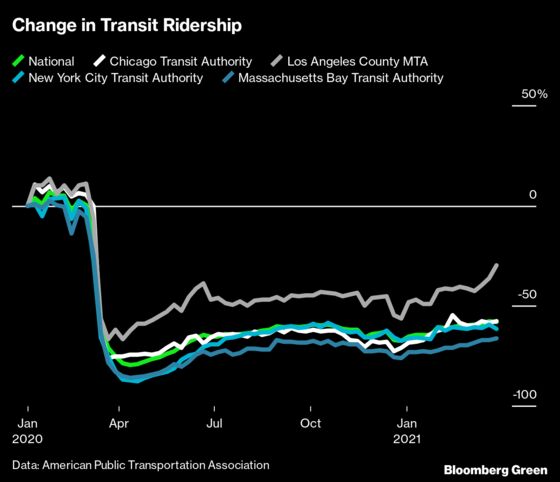

It’s still not enough for many longtime passengers. Subway ridership in March was 30% of its pre-pandemic level, when the MTA transported 5.5 million straphangers daily. The most recent agency survey showed that 71% of its lapsed customers were very concerned about being able to socially distance on trains.

Ridership losses during the pandemic have had catastrophic effects for public-transit agencies around the country, and none has lost more people in total than the MTA. In addition to the subways and buses, the agency operates two commuter railroads. Customer fares cover 38% of its annual $17 billion budget, and Covid-19 eliminated most of that revenue. The MTA threatened to slash subway service by as much as 40% last fall, but it’s been able to stave off cuts, thanks to $14.5 billion in federal stimulus it’s received in the past year—including, most recently, $6.5 billion in President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act. It also borrowed $3.4 billion from the Federal Reserve.

The MTA says it should have enough money now to survive until 2023 without major changes. But even then, the agency will be ailing. Many customers have gotten comfortable doing their job at their kitchen table in their athleisure wear. “The habit of going to work has been broken,” says Mitchell Moss, director of New York University’s Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management.

The agency has no illusions. It predicts that by the close of 2024 its passenger head count may still be only 86% of what it was before the pandemic. That means an annual recurring structural deficit of $1 billion, says Feinberg’s boss, MTA Chairman Patrick Foye. This doesn’t bode well for the perennially underfunded subway, which has lurched from crisis to crisis since its inception in 1904.

It also threatens the ability of Biden, who established his transit bona fides as a champion of Amtrak, to lay the groundwork for the U.S. to meet his ambitious goal of being carbon neutral by 2050. “Now is the time to improve the air we breathe and tackle the climate crisis by moving the U.S. to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, building a national electric-vehicle charging network, and investing in transit-oriented development, sustainable aviation, and resilient infrastructure,” Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg told a House committee on March 25. Six days later, the president announced a $2.5 trillion infrastructure proposal with $85 billion for mass transit, saying it would reduce pollution.

For decades, New York has been a shining example of the difference trains and buses can make. New Yorkers are fond of noting that their city’s per capita greenhouse gas emissions are a third of the national average. Part of the reason is because so many live within walking distance of the 665-mile-long subway system, making it possible to forgo automobile ownership altogether. Indeed, Feinberg says its raison d’être is removing people from cars.

The pandemic disrupted that balance. As subway ridership fell last year during the pandemic, there was an increase in bike sales, but car registrations in the city rose by 9% in December compared with the final month of 2019, according to the New York State Department of Motor Vehicles. If such a shift could happen in New York, what hope does Biden have of preventing larger numbers of Americans from abandoning public transportation, no matter how much money he throws at it? “That just makes the challenge immensely harder,” says Andrew Salzberg, creator of the Decarbonizing Transportation newsletter.

In other words, one could argue that much more than New York’s survival depends on Feinberg wooing back subway riders. Her campaign is complicated by a homelessness crisis, a spate of lurid subway crimes, and personal animosity between her political patron, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (now being investigated for alleged sexual harassment), and the lame-duck politician who runs the city, Mayor Bill de Blasio. As if that weren’t enough, there’s her fundamental challenge of having to persuade New Yorkers to once again embrace a system that even in the best of times can be difficult to love.

Feinberg, 43, grew up in Charleston, W.Va., and didn’t set foot on a subway until she moved to Washington, D.C., when she was 22 years old. “I thought the most grown-up thing I did was getting on a subway train,” she says.

She was there to pursue a career in government that led to a post as a senior adviser in the Obama White House in 2009. She departed after a year and a half to do a stint in the private sector—first as global communications director at Bloomberg LP, publisher of Bloomberg Green, and later as a policy director at Facebook Inc. She returned to the political sphere in 2013 to be the Department of Transportation’s chief of staff. Two years later, Feinberg was running the Federal Railroad Administration, the primary safety regulator for the country’s public and private railroads.

She was already a fan of the New York subway when she moved to the city in 2017 after starting her own communications company. Now she became intimately familiar with it. Locals habitually grumbled about the system; Feinberg thought they were being provincial. “I was just stunned,” she says. “I was like, ‘Do you have any idea how good this service is? You can ride the system anywhere and walk to where you are going.’ ” The same year, Cuomo named Feinberg to the MTA board. For much of that time, MTA’s subway chief was Andy Byford, a beloved figure whom riders referred to as “Train Daddy.”

In January 2020, Train Daddy quit, and the following month the governor asked Feinberg to step in on an interim basis. City & State, a local news organization, dubbed her “Train Foster Mom.” She planned to be there for only a few months. Then the pandemic set in, and she found herself embroiled in a conflict with her employees.

By early March, riders had started to wear masks. Train operators and conductors wanted to wear them, too, but the MTA said no. Workers suspected the authority was more concerned with fares than their health. “They didn’t want us to scare people,” says Ben Valdes, a train operator.

In hindsight, Feinberg says the MTA should have permitted employees to cover their face sooner. She says the agency was relying on the CDC’s early guidance that the masks weren’t needed by the general public. “Eventually we got in front of them and said this guidance makes no sense,” she says.

Even so, the virus cut a swath through the MTA’s workforce, claiming the lives of more than 150 employees. The agency agreed to pay the families of the deceased a $500,000 death benefit. Feinberg formed a liaison group to provide survivors with whatever they needed, whether it was filling out insurance paperwork or retrieving a loved one’s possessions from their locker. “You are going to hold their hand through the whole thing,” she remembers telling the group.

As New York became the epicenter of the pandemic, the MTA debated whether to discontinue subway service. Ridership had dwindled to about 400,000 people a day, but these were essential workers who toiled in hospitals and grocery stores. At the same time, homeless people took up residence on the almost empty trains, creating what Feinberg feared was a social distancing nightmare.

Despite their lack of fondness for each other, Cuomo and de Blasio reached a deal in late April. The MTA would close the subways to passengers from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m. The New York City Department of Social Services, working with the police, would empty the trains of homeless riders. Advocates for the homeless were aghast, saying the city and state should have been doing more to address the root causes of homelessness rather than throwing destitute people off the trains. Feinberg is unapologetic. She describes many of the homeless riders as hard cases who’d refused help in the past. She estimates that about a third of the 2,000 removed from the subway finally agreed to go to shelters. There was another benefit: With the trains empty, the MTA could clean them thoroughly so riders would feel more confident returning.

By the summer the initial panic at the agency had begun to subside. There were no Covid-related deaths among its workers from early May until the end of September. A study commissioned by the American Public Transportation Association found no direct link between urban transit use and transmission of the virus. With fewer straphangers crowding the subway and holding doors open, the MTA could take pride that its on-time performance reached almost 90%, its highest in years. Customers began to trickle back.

Yet, even though there were still fewer people on trains, certain categories of subway crime rose. There were freakish incidents where mentally disturbed people pushed travelers onto the tracks. The numbers of robberies, rapes, and murders, while still relatively low, were higher in 2020 than the previous year. Assaults on subway workers climbed, too. “Covid-19 has really had this inexplicable, full-moon effect in the New York City transit system,” says John Samuelsen, international president of the Transport Workers Union and a member of the MTA’s board. “It’s turned into a very, very dangerous place.”

Feinberg pleaded with the de Blasio administration to provide more police and asked the city to change what she describes as its policy of not sending mental health specialists into the subway. But, she says, she got nowhere. “This City Hall generally thinks of the subway system as out of sight, out of mind,” she says. “Frankly, this mayor doesn’t ride the subway.” Mitch Schwartz, a de Blasio spokesman, responds: “Interim President Feinberg’s personal attacks against the mayor are bizarre, but they won’t affect City Hall’s good-faith partnership with her agency.”

In early February, Feinberg visits two stations where heroin use has been reported. The first is on 125th Street in East Harlem. Downstairs on the platform, Pat Warren, the MTA’s chief safety officer, waves for Feinberg to come look over the edge. Dozens of hypodermic needles litter the southbound tracks, with even more on the northbound side. “Good God,” she says.

At a Washington Heights station where addicts have been openly shooting up, she’s pleasantly surprised. There are none to be seen tonight, and the station has largely been swept of drug paraphernalia. “They must have known you were coming,” says Joe Nugent, a retired New York City police lieutenant who serves as the department’s liaison to Feinberg’s division.

Upstairs there’s a panhandler who can be seen most days at the station holding open the emergency exit and soliciting donations. Feinberg doesn’t say anything about that. She’s also passed plenty of people entering the subway illegally. Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. said in 2018 that he would no longer prosecute most of them because he didn’t want to criminalize poverty.

But then Feinberg and Nugent notice the man passing cash to someone hurrying through the door. It looks like a drug deal. Nugent strolls over to the doorman. “Hey, boss,” he tells him. “Get lost.”

The fellow doesn’t budge. He baits Nugent, saying he doesn’t believe he’s a police officer. Nugent takes out his phone and dials the local precinct. “Go ahead,” the man says. “It will take them 15 minutes to get here.”

He steps away from the exit and leans against the wall, looking at his own phone with a bored air. Finally he climbs the stairs to the street and doesn’t return.

Still, the police don’t arrive. Nugent and Feinberg leave. “They’ve got my number,” Nugent says. “They’ll look around, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, he’s gone.’ Then he’ll come back.” (A few days later, the man is at the door again.)

Despite what she’d witnessed in the subway, Feinberg was upbeat. She was excited about Biden having been sworn in the month before. His administration was likely to speed the approval of the MTA’s congestion pricing plan for Manhattan, which promised to reduce air pollution in the city and was expected to raise $1 billion a year for much-needed transit upgrades. (It had been stalled under President Donald Trump.)

Feinberg was also preparing to welcome back hitherto reluctant passengers with zesty new announcements for the subway and buses by famous city dwellers such as comedian Jerry Seinfeld, actress Awkwafina, and rappers Young M.A and Jadakiss. The stars were all doing it for free. On Feb. 12, Feinberg made the rounds on morning TV news shows to unveil the announcements. “Sarah, I didn’t know you were a hip-hop fan,” a morning anchor said. “Jadakiss, Young M.A?”

“I love it so much,” she replied.

That night, a homeless man stabbed four other homeless people on the A line, two of them fatally. The Washington Heights station that Feinberg had toured little more than a week before was the site of two of the incidents. The perpetrator was arrested nearby carrying his bloody weapon.

Feinberg found herself talking about crime when she would have rather been discussing hip-hop. She called for the city to add 1,500 police officers to the subways. The de Blasio administration deployed only an additional 644. “I don’t want to run a transit system that feels militarized,” she says. “But I also know my customers. They’re all saying, ‘I want more police.’ ” The MTA’s most recent customer survey showed that 73% of subway riders were very concerned about crime and harassment, which outweighed their worries about social distancing and mask-wearing on trains. (A de Blasio spokesman says the extra police show the mayor’s commitment to restoring confidence in the subway even at a time when crime is historically low.)

But there were some things the MTA could control. In March, Warren, the agency’s safety chief, said the Covid positivity rate for MTA employees was 2.9%, compared with the city’s overall 4.2%. The MTA attributes this to an in-house testing program it started last fall. It was also the first U.S. transit agency to create its own vaccination centers.

Feinberg appears in late February at the opening ceremony of the first one, in Brooklyn, with Chairman Foye. As bus and subway workers await their jabs, a reporter points out that she’s approaching her one-year anniversary on the job. He asks Foye why Feinberg is still interim president. “That’s your way of saying happy anniversary?” Feinberg interrupts. “When we get to the other side of this, Pat and I will sit down and figure it out.”

It’s a legitimate question. The subway’s long-term challenges are formidable, and they exemplify those of the Biden administration as it banks on public transit as a climate solution. Covid has broken the historic contract between transit agencies and their passengers, many of whom will no longer be required to ride trains, buses, and subways into the office five days a week. In a post-pandemic world, some workers may grace the office with their presence only three days. Others may show up less frequently.

Either way, it will be a significant hit to the fare box, making it harder for the transit agencies to maintain service levels. In January almost a third of the top U.S. providers were running 80% or less of their pre-Covid schedules, according to TransitCenter, a foundation. But this was before the Biden stimulus showered the sector with a total of $30 billion in aid.

The problem with cuts is that they can lead to a transit death spiral. Passengers return to subways only to give up on them because their odyssey has grown too Homeric. Agencies must slash service more to compensate for lost fares, causing more riders to flee. The danger is, no longer tethered to offices, white-collar workers not only jettison subways, but they relocate to less populated areas where their life revolves around cars. “That’s the big fear,” says Eric Sundquist, director of the University of Wisconsin’s State Smart Transportation Initiative.

Even with the likelihood that more money is on its way from the federal government, Feinberg says transit agencies need to reconsider their spending. “Our budget is bloated,” she says. “We have a budget that’s bloated. There’s going to be a reckoning, whether it’s over how many people are employed at this agency, what their job description is, or what we end up paying for multiyear projects. This all just has to be scrutinized in a way that frankly I don’t think it really has before.”

Luckily, Feinberg had some encouraging news recently. With spring approaching, the subway carried 1.9 million passengers on March 11, its highest daily number since the pandemic began. (Four weeks later, on April 8, a new record was set of two million.) “All it takes is a little good weather,” she says. —With Michelle Kaske

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.