Biden $400 Billion Care Plan Would Have a Caveat: States Opt In

Biden $400 Billion Care Plan Would Have a Caveat: States Opt In

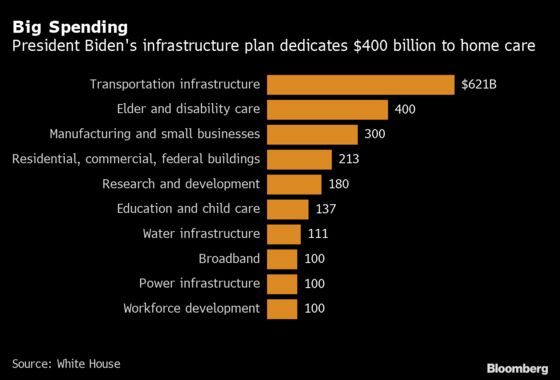

(Bloomberg) -- President Joe Biden’s ambitious $400 billion plan to improve in-home care for the elderly and lift wages for millions of workers may be limited by states’ ability to opt out, based on early proposals from Congress.

The leading legislative draft in discussion would channel the funds through the U.S. government health-insurance program Medicaid and tie the money to higher reimbursement rates and training for in-home workers, according to congressional aides familiar with the matter who declined to be identified because the deliberations are private.

Funding through Medicaid, which already handles payments for most personal-care services for seniors and people with disabilities, is seen as the fastest and most direct way of getting the money out.

But states, which administer Medicaid, would be responsible for ensuring that higher wages get passed down to workers and would have the option to take the federal money or not, according to the people. This would be similar to Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, which a dozen states haven’t adopted. The proposal hasn’t been finalized and details could change as talks continue.

Going through Medicaid would limit Biden’s home-care plan in scope, and increase inequities along state lines. Some of the worst-paid home-care workers -- a vast majority of whom are women, minorities and immigrants -- are in southern and Republican states that haven’t adopted Medicaid expansion under Obamacare.

Low Wages

The mammoth task of overhauling home care in the U.S. illustrates the many challenges the Biden administration faces in implementing and funding his $4 trillion economic proposals. As the population ages, in-home care workers have become one of the fastest-growing segments of the labor market, and yet they are currently paid so poorly that one in six live in poverty, according to Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute, a New York-based nonprofit that advocates for care givers.

“It’s significant, it’s historic, but it’s just the first step,” Robert Espinoza, vice president of policy at PHI, said of Biden’s plan. “It might be successful, but in a measured way. There may be inequities in the success.”

The plan is now in the hands of Congress, where at least four committees are crafting a bill with input from interest groups for the aging, disabled and labor communities.

The main proposal is led by Senators Bob Casey, Maggie Hassan, Sherrod Brown and Representative Debbie Dingell, all Democrats. To encourage buy-in from states, their draft calls for the federal government to pay most or all the costs for the first few years, the aides said.

Medicaid is the largest payer for long-term support services such as home care. Its Home and Community Based Services program is optional for states, which has led to a patchwork system with different eligibility, plans and financing in each state.

The president supports investing the funds in HCBS, said an administration official, who declined to be identified because the proposal isn’t final. Since the Congress is still working on legislation, the White House hasn’t yet weighed in on the mechanics and many options are still on the table, the official said.

Care Quality

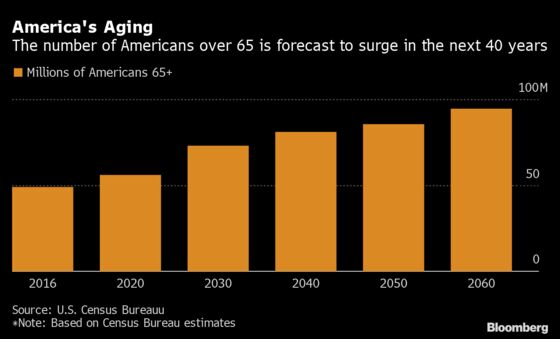

The Biden administration aims to improve the quality of care for the 14 million elderly Americans who will need the services in four decades -- double today’s level. The need for in-home care workers, which has already exploded to almost 2.4 million in 2019 from fewer than 1 million 10 years earlier, will only increase.

“It’s incredibly important that the jobs created in home health work are good jobs,” said Heather Boushey, a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers who focuses on child and elder care.

Most home care is paid through Medicaid via a “fee-for-service” platform. Many workers are contractors, rather than full-time employees, meaning they’re deprived of federal wage protection. The system of training is also fragmented, and career advancement is difficult. This contributes to high turnover and lower job quality.

Creating good-paying union jobs is one of Biden’s selling points for his economic overhaul. Advocacy groups are pushing for measures that go beyond Casey’s legislative draft to achieve that goal, although they are facing resistance and may not be adopted. The general idea among Democrats crafting proposals is to leave it to states to decide how the money should trickle down to workers.

Union Push

The National Domestic Workers Alliance has floated creating health-care “hubs,” where consumers could find care and workers would get trained. This would minimize the need for private agencies that currently do this. The new entities could also handle payroll and lead negotiations for higher wages, something that the Service Employees International Union is pushing for, according to the people.

“There’s the public health benefit, the safety for the care workforce, and the economic stimulus and the overall growth of the economy,” said Haeyoung Yoon, senior policy director at NDWA. “We want everyone to be earning family-sustaining wages and having a real shot at that economic security.”

SEIU, which represents about 740,000 home-care workers and is the lead union in the talks, has proposed to go a step further and let the new entities assume the role of employers, according to two people familiar with the thinking.

SEIU President Mary Kay Henry, in an e-mailed statement, urged Congress to “quickly pass the American Jobs Plan and this bold investment in good, union, living-wage care jobs.” The union didn’t address questions about the structure of the legislation.

Lydia Nakiberu will provide a litmus test for Biden’s in-home care plan.

The 42-year-old mother of three works 12-hour shifts several days a week, bathing, feeding, and administering insulin to an elderly man with dementia in Pepperell, Massachusetts. The money she earns, without benefits or danger pay during the pandemic, makes it difficult for her to pay gas, electricity and mortgage payments on time.

“In our job, we are undervalued, we are underpaid,” said Nakiberu, who’s an NDWA member. “If they raise our wages, that will definitely improve our lives.”

A thorny sticking point in the policy talks has been how to divvy the funds to balance the needs of the workforce and the people they care for.

“That’s what the calculation is right now -- how big can we go in order to create an entitlement for these services while also ensuring that the workforce is paid a family-sustaining wage,” said Nicole Jorwic, senior director of public policy at the Arc of the United States, which advocates for people with intellectual and development disabilities. “It has to be a ‘Both, And’, which is what Congress is grappling with.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.