Beekeeper’s Plight Flags $109 Billion Remittances Problem

Beekeeper’s Plight Points to $109 Billion Remittances Problem

(Bloomberg) -- Since the breakup of the Soviet Union three decades ago, Khatam Khaydarov has helped support his family in Uzbekistan by traveling over 1,500 miles to work in Russia for months at a time. Not this year.

Khaydarov, 62, was visiting his home in Samarkand in March when Russia and Uzbekistan shut their borders to halt the spread of the coronavirus. The beekeeper has lost about 60,000 rubles ($858) in income since then, and has been living off savings.

“Naturally I send money home when I work in Russia,” he said. “We didn’t have much in savings, but what little we had has been spent during the quarantine.”

Khaydarov’s plight is a microcosm of a wider problem for some smaller emerging economies, which often rely on money sent home from emigrants. The World Bank expects remittances to lower and medium income countries to fall $109 billion, or 20%, this year, the sharpest decline in recent history. Europe and central Asia will likely be worst hit.

Border closures imply a “doubling or a tripling of the impact” of coronavirus for some economies, according to European Bank for Reconstruction and Development economist Eric Livny.

“You can’t go to Russia and you can’t find a job at home,” Livny said. “Not now, not in the near future.”

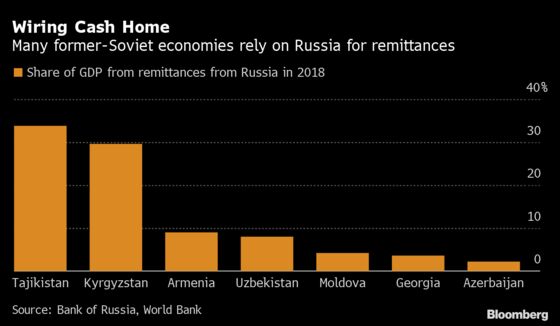

For decades, remittances from commodity-rich Russia have been propping up poorer nations in the former Soviet Union, with some countries relying on the income for as much as a third of economic output. In turn, Russia, which has a shrinking population, benefits from the influx of cheap labor.

Georgia saw money sent home drop by more than 40% in April, while Tajikistan, which is one of the most remittance-reliant countries in the world, posted a 50% decline in March and April.

“For many of the most vulnerable families, that will be 100% of their income,” Livny said.

Khaydarov, the beekeeper, is one of over a million Uzbeks who will either return from Russia or not go there to work this year, according to Bakhtiyоr Ergashev, director of the Tashkent-based Ma’no Centre for Research Initiatives.

Uzbeks sent home half as much money in April from the year earlier, according to its central bank, as employers fired workers during lockdowns and border closures kept migrant workers home.

The International Monetary Fund has raised its unemployment forecast for Uzbekistan this year to 16.5% from 8.9% - though official unemployment figures may underestimate the problem. The Uzbek government is creating job programs to soften the impact, Ergashev said.

“If these people don’t find jobs, it is possible that social tension will grow in the country,” he said.

Even if borders reopen, migrants will be seeking work in an economy that is set for its biggest slump in more than a decade this year. The drop in global oil prices has made the Russian government reluctant to dig deep into reserves to soften the blow from the coronavirus lockdown, meaning incomes have slumped and unemployment has surged.

Still, Khaydarov is just waiting for the word to make the trip to Ufa, capital of the Bashkortostan republic between the Ural Mountains and the Volga River.

“If the borders were going to open now, I would go to Russia immediately,” he said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.