Beef Is Becoming a Luxury for Millions in Brazil

Beef Is Becoming a Luxury for Millions in Brazil

(Bloomberg) -- Living on the outskirts of Cuiaba, Carlos Ferreira is surrounded by cattle grazing on some of the richest pastures in Brazil. Yet he can no longer afford a steak.

The 34-year-old was a regular beef eater. But as the city locked down, he lost his jobs in a florist shop and as an Uber driver. Now he and his unemployed wife have to scrape by with help from the government and relatives.

“Before I lost my job, we could afford to eat steak almost every day,” the physical education graduate said. “Now we have enough for chicken, eggs and sometimes cheap fish.”

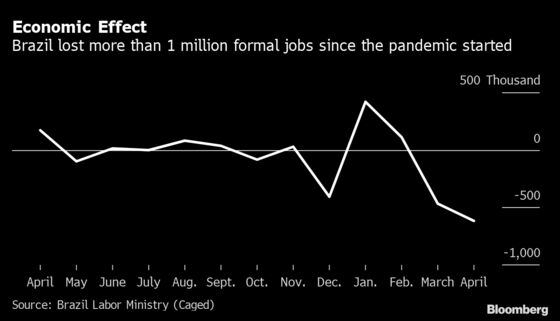

With farming land covering an area roughly the size of Texas, Brazil plays an increasingly important role in feeding the world. But as the country becomes a virus epicenter and more than a million formal jobs are lost, more Brazilians like Ferreira are struggling to put food on the table. The impact on consumption behavior may last for years.

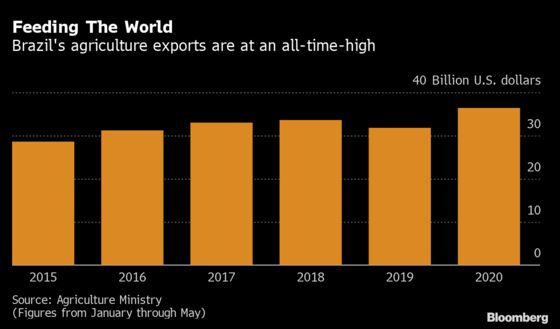

The irony is that agribusiness is booming in the country.

Brazil is already the top exporter of soybeans, beef, chicken, sugar, coffee and orange juice. A combination of record crops, strong global demand and a plunge in the local currency means 2020 will be its best year yet. The government expects farming revenue to grow 8.5% to a record 704 billion reais ($136 billion). Helping drive demand is a protein gap after African swine fever decimated China’s hog herd.

But the industry is dominated by large players with a heavy export focus. Shares in meatpackers JBS SA, Minerva SA and Marfrig Global Foods SA have rallied in the past few months along with the local equity benchmark.

“Agribusiness focused on exports is doing great, but the portion of the sector dedicated to the local market is suffering a lot,” Paulo Sousa, who heads Cargill Inc. operations in Brazil, said last week. “It’s clear that consumers are cutting food expenses.”

Access to food in developing nations like Brazil was unequal long before Covid-19. But the pandemic is deepening the chasm and exacerbating food insecurity for low-income earners in the South American country, including 38 million informal workers with little access to credit or state help.

To add insult to injury, food is getting pricier thanks to strong export demand and an initial spate of panic buying when the outbreak hit, the U.S. Department of Agriculture said in a report on Brazil last week. Food was the only category showing inflation in the first four months of the year, according to Brazil’s statistics institute.

Consumption of high-end meat cuts, dairy and some crop-based products like sugar in beverages have fallen in Brazil since the isolation measures started in mid-March. The impact on meat consumption will only increase, according to Thiago de Carvalho, researcher at the Center of Advanced Studies on Applied Economics of University of Sao Paulo, or Cepea.

After moving to cheaper beef cuts, many Brazilians probably will replace part or all of their beef consumption with cheaper proteins like chicken and pork. Overall demand, which has been propped up by the government’s income aid, is set to fall when that aid finishes in the coming months, he said.

“Lower income earners will have no more options and may stop consuming meat, not only beef, with protein consumption limited to grains, eggs and cheap processed food, such as sausages,” he said.

Brazil’s beef consumption -- the world’s third largest -- is seen falling 10% this year as the economic crisis erodes purchasing power and isolation constrains the food-service segment, said Cesar de Castro Alves, an agriculture consultant at Itau BBA. Chicken and pork demand won’t increase enough to offset the drop in beef, meaning consumption of the three types of meat is likely to fall 2% in 2020, he said.

Also, the history of economic downturns in the country shows consumption changes can linger. Brazilians are eating less sugar and beef than they did in 2014, a year before the country’s worst recession, said Felipe Novaes, an economist at Tendencias Consultoria.

And the pain of this year’s crisis could just be starting.

“We got the money from the last monthly government aid,” Ferreira said. “We don’t know if this support will continue. So far, we have no income for July.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.