Banks Snared in Race Conversation, Confronted by Bleak Legacy

Banks Snared in Race Conversation, Confronted by Bleak Legacy

(Bloomberg) -- A picture of JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief Jamie Dimon kneeling in a bank branch, seen across the industry as opposing the mistreatment of Black Americans, is doing little to win over activists.

On Friday, about 100 protesters amassed outside his firm’s tower in midtown Manhattan, where an organizer with a bullhorn led the crowd in a call-and-response: “JPMorgan -- Shut it down! JPMorgan -- Shut it down!”

As the group moved on, Cristo Braz walked a few blocks and sat on the street, venting frustrations over racial inequality. “This is not just a social injustice,” Braz said of the broadening U.S. protests. “This is also an economic injustice, economic apartheid.”

Like many in corporate America, bank leaders have rushed to denounce racism and offer overtures to minority groups after the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man killed by police during an arrest in Minneapolis. Yet as demonstrations against racial injustice and inequality enter a fourth week, the industry is increasingly getting singled out over its involvement in creating and prolonging economic gaps. Activists say they plan to ramp up pressure on banks to address that legacy.

On the sidelines of protests, organizers are spreading the word about banks’ roles in some of the worst chapters of U.S. history, from financing slaveholders to systemic discrimination in 20th century mortgage lending known as redlining, which denied generations of minority families the chance to buy a home. Activists are also trading statistics on the lack of diversity within banks and discussing lending and lobbying practices they say hurt minority communities.

Jennifer Epps-Addison, the president of the social-equity group CPD Action, was walking home from a rally in Los Angeles when the picture of Dimon taking a knee in front of a massive vault popped up on her phone. Disgusted at seeing a top banker in that symbolic position, she swore out loud.

Epps-Addison said the image immediately raised questions about the diversity of the bank’s leaders and what they have done to right past wrongs. The firm, she said, should be hiring and promoting members of minority groups, reorienting core banking businesses and using its clout in Washington to enact measures to address disparities.

“They could use their lobbying power and influence for good and not evil,” she said in an interview. “Which means supporting things like reparations at the federal level, universal health care, access to college.”

Joe Evangelisti, a spokesman for JPMorgan, said the bank has been “working hard on many of the diversity and hiring issues Ms. Epps-Addison raises.”

Representatives for JPMorgan declined to specify Dimon’s intent in the picture and referred to his statement on the need to address the past.

“We have a collective responsibility to stand up and take serious action to address centuries of structural racism,” Dimon said. “We can all do better and do more. Our words and actions matter.”

A growing number of political leaders and cultural icons -- including Barack Obama, Spike Lee, Cornel West and Jane Fonda -- have added to pressure on the industry recently, drawing lines in public appearances between its legacy and the conditions stoking protests.

Robert Reich, the Clinton-era labor secretary who now researches public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote a piece for the Guardian on Sunday that listed Dimon’s photo among a variety of statements by corporate leaders including BlackRock Inc.’s Larry Fink and Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s David Solomon. “Most of this is for show,” Reich said, describing examples of companies working against the interests of minorities.

JPMorgan’s Evangelisti called that comment “ridiculous and ignorant.”

Just days before Floyd’s death, the industry scored a partial victory in a long campaign to make it easier to comply with the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act, a law intended to undo redlining. While backers predicted the changes will spur investment in poor areas, fair lending advocates have condemned the moves as gutting the law.

Occupy Wall Street

“Banks’ actions really underline a lot of the economic divide and the wealth gap that we see among the races in this country,” said Darrin Williams, a former state politician who now runs community development lender Southern Bancorp Inc. in Arkansas. A minister’s son, he grew up surrounded by Black church leaders who deposited their Sunday collections into local banks that were unwilling to lend to members of the congregation.

Even today, he said, banks “are happy to provide a deposit account and happy to provide a checking account, a transactional account, for people of color. But they’re all too often not providing access to real capital for investment and growth.”

Such criticisms echo some of the attacks the financial industry faced in the Occupy Wall Street movement that followed the 2008 financial crisis. In the years since, banks have tried to recast themselves as a force for social good. They have adopted more-inclusive policies for staff and curtailed at least some lending to controversial industries. Some banks also launched targeted initiatives, such as JPMorgan’s vow to invest $200 million to support the revitalization of Detroit.

Days after Floyd’s death, Goldman Sachs pledged to create a $10 million fund for grants to help address racial and economic injustice. Bank of America Corp. promised $1 billion over four years to provide additional support to communities where racial and economic inequality is being exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic.

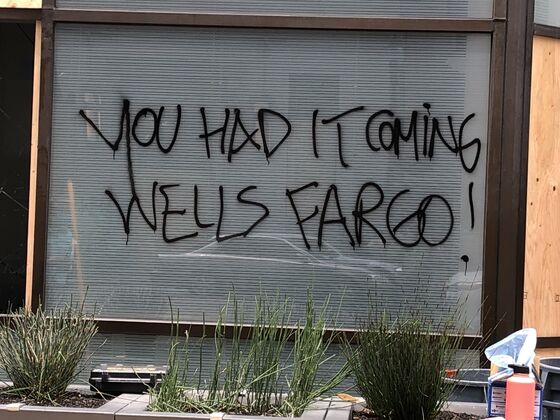

Still, in recent weeks, vandals have attacked Bank of America locations around the country. In San Diego, a pair of JPMorgan and Union Bank branches burned. In Oakland, vandals left graffiti that spanned a storefront: “YOU HAD IT COMING WELLS FARGO!”

Temporary initiatives won’t be enough, said Bill Daley, Wells Fargo & Co.’s vice chairman for public affairs, who said the firm is looking at making permanent changes.

“We’re going to be trying to look at things really differently than just, ‘Oh we’re going to commit $1 million to this and $50 million to that,’ and stuff that we were going to do anyway,” said Daley, who previously served as chief of staff in Obama’s White House and is a scion of the Chicago political family. “That’s just the same old, pardon me, bulls--- that everybody has done before, and that’s where our credibility then becomes zero.”

Finance leaders have pledged for years to diversify workforces and management but failed to notch much progress. At a number of firms, relatively small percentages of Black employees and managers in the U.S. have stalled or even declined.

Of the more than 80 people now listed on the elite executive teams atop the six largest U.S. banks, only one is Black: Citigroup Inc. Chief Financial Officer Mark Mason. Recently, Wells Fargo and Morgan Stanley announced they each plan to add a Black executive to their committees in coming weeks.

The lack of Black leadership in the industry is key, because it is “absolutely” linked to unfair practices, said Lisa Cook, an economics and international relations professor at Michigan State University. “It should belong in any discussion of wealth: Where are the Black bank executives?”

‘Lip Service’

About 17% of Black households in the U.S. were unbanked and another 30% were underbanked, according to a 2017 study by the Federal Desposit Insurance Corp. The comparable figures for White households were 3% and 14%.

A study this year showed minority-owned businesses were less successful in getting banks to arrange emergency federal loans to weather the pandemic. Many lenders gave priority to existing customers, yet Black-owned enterprises are typically underrepresented among bank clients, so were at greater risk of being left out.

Banks must help more minority-owned and women-owned companies tap markets, buy from more diverse suppliers and extend more credit in underserved communities, said Cynthia DiBartolo, CEO of broker-dealer Tigress Financial Partners.

“This has to be more than just lip service,” she said of banks’ recent statements. “There has to be some soul-searching.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.