China Scientist’s Claim on World’s First Gene-Edited Babies Sparks Denials

Mystery swirled around a Chinese researcher’s claim to have produced the world’s first genetically-edited babies.

(Bloomberg) -- A Chinese researcher claims to have created the world’s first genetically edited babies, crossing an ethical frontier and prompting a backlash from health officials and other scientists.

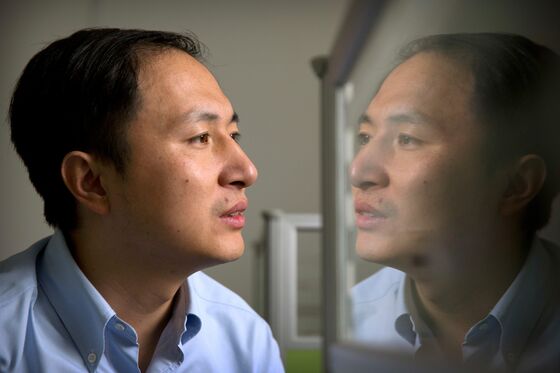

He Jiankui, a researcher in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, said he altered the genes of a pair of twin girls born this month while they were embryos, the Associated Press reported. The goal was to make the babies resistant to the virus that causes AIDS, the scientist said.

The report prompted disavowals from several Chinese health institutions, and China’s National Health Commission asked regional authorities to investigate. He’s claim, if confirmed, would force the field to grapple with concerns about the ramifications of the emerging science of gene editing and what price the babies -- and their descendants -- might pay in terms of unexpected consequences.

The technology has made substantial leaps in recent years with tools like Crispr that enable relatively easy editing of single genes, creating the potential for misuse or deployment outside of established scientific and ethical norms. Doctors are already trying to use the technology to repair defective genes in patients, but that’s far different from fiddling with healthy ones in embryos.

He’s work drew international criticism for its lack of transparency -- with the researcher speaking on a YouTube video instead of at a scientific meeting or in a journal -- and for potentially turning public opinion against other work in the area. He was not available to comment, his spokesman said.

Pouring Fuel

“It’s really pouring fuel on the fires of controversy,” said Sarah Chan, director of the Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Sciences and the Law at the University of Edinburgh. “It’s going to polarize people, for people who are perhaps skeptical about the science or worried about our ability to regulate it properly.”

On Monday, several Chinese bodies distanced themselves from the work. While He told the AP he had received approval from Shenzhen Harmonicare Women’s and Children’s Hospital, the Hong Kong-listed company that owns the medical center said it had no knowledge of such permission being granted, according to Cai Jiangnan, a member of the board of Harmonicare Medical Holdings Ltd.

The Harmonicare hospital is now organizing a “crisis response” to the news in an attempt to verify what happened, said Cai. “I think it needs to get approval from the government,” he said. “This kind of big thing, I don’t think any hospital would do this ahead of time without getting any government approval.”

He’s team used a tool called Crispr-cas9 to disable a gene involved in HIV’s entry to cells, according to the AP, which said the scientist claimed to have altered embryos for seven couples. All the men involved were HIV positive, and part of a married couple that suffered from infertility. They signed informed consent forms, according to the Chinese clinical trial register. According to He’s YouTube video, the twins were born a few weeks ago.

“Gene surgery is and should remain a technology for healing,” He said in the video, which was posted on Nov. 25. “Enhancing IQ or selecting hair or eye color isn’t what a loving parent does. That should be banned.”

In a separate video, He defended the ethical basis of his research, according to a report from ScienceNet.cn, a government-backed publication of China Science Daily, citing an unpublished YouTube segment.

“I know my work is controversial, but I believe these families need this kind of technology. For them, I’m willing to take criticism,” He said in the video, according to ScienceNet. “We believe ethics are on our side of history.”

Probe Underway

For parents at risk of passing on inherited conditions, genetic screening of embryos before they’re implanted is probably more useful in all cases than genome editing would be, said Ewan Birney, director of EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute.

“You really don’t need to do this for the benefit of the children,” Birney said. “So all of that points toward scientists who are just so keen to do it.”

A woman answering the phone at Harmonicare’s investor relations office said a probe was underway. The ethics committee of Shenzhen’s Health and Family Planning Commission said it was not informed of the experiment and is looking into the matter, Chinese media reported.

The Southern University of Science and Technology said in a statement posted on its website that it was “shocked” at the news and that He has been on unpaid leave since February. The university administration and the biology department, of which He is a member, had no knowledge of He’s experiments, it said.

Hospital Form

The school said it views this as a serious violation of academic ethics and regulations and will appoint independent experts to investigate.

A listing for the clinical trial on a public database appeared to show a form stamped by the Shenzhen Harmonicare hospital, although that couldn’t be independently verified.

News of the experimental treatment prompted fierce criticism from experts online. The procedure was “unbelievable and unacceptable,” Li Jingsong, a cell researcher at the China Academy of Sciences, said on WeChat.

China has streamlined drug industry regulation since 2016 in response to growing demand from its population for quality health care. The reform unleashed a wave of new medical research in China, with both local and foreign scientists studying techniques and medicines beyond what’s currently being done in the U.S or Europe.

He is the founder and chairman of Direct Genomics, a gene-testing startup based in Shenzhen, according to a Chinese government-run website on companies. Sina.com, an established Chinese news publication, reported in April that Direct Genomics received 218 million yuan ($31 million) in venture capital funding that month.

To contact Bloomberg News staff for this story: Bruce Einhorn in Hong Kong at beinhorn1@bloomberg.net;Daniela Wei in Hong Kong at jwei74@bloomberg.net;Rachel Chang in Shanghai at wchang98@bloomberg.net;Naomi Kresge in Berlin at nkresge@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: K. Oanh Ha at oha3@bloomberg.net, ;Eric Pfanner at epfanner1@bloomberg.net, John Lauerman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Editorial Board