At Venezuela’s Houston Outpost, Chaos and Hope for Emancipation

At Venezuela’s Houston Outpost, Chaos and Hope for Emancipation

(Bloomberg) -- Behind a steel fence, past security guards and beyond the bronze statue of peasants toiling toward a heroic socialist future, lies one of the few remaining prizes of Venezuela’s ruined economy.

It’s in Houston, not Caracas.

Inside the glass-box headquarters of Citgo Petroleum Corp., the American subsidiary of state petroleum giant Petroleos de Venezuela SA, a corporate drama is playing out that mirrors the one in the stricken nation.

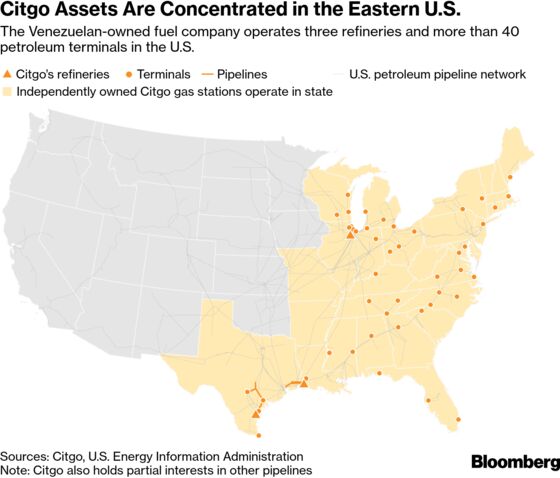

Even as PDVSA’s production has dropped by almost half in four years, Citgo’s gasoline refineries in Texas, Louisiana and Illinois account for about 4 percent of U.S. fuel-making capacity and represent the best-functioning part of a shambolic operation. But workers are split between loyalists of strongman Nicolas Maduro and those of Juan Guaido, who says he is the rightful president and who this week named a competing set of board members.

Ushered Out

Six former Citgo executives are jailed at the military-intelligence center in Caracas and a former company head died in custody. Customers and vendors have been spooked by U.S. moves against the country. Last week, a gun-toting deputy guarded the Houston building’s lobby after sanctioned Venezuelans hastily departed. Through it all, technicians have slogged through their daily work lives, scrupulously avoiding discussion of politics and hoping for an easier path ahead.

Interviews with current and former employees at headquarters and refineries revealed a company at a turning point. Citgo is free for the moment from political interference, cronyism and corruption, but lacks leaders to chart a path forward. Most of the workers spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution for themselves or colleagues, including firings, family harassment or even arrest by a regime accused of human-rights abuses and killings.

“We’re in this limbo,” said an upper-level American executive. The company has been held back by PDVSA, he said, but now employees can focus on operations and “stop all the insanity.”

Press offices for PDVSA and Citgo didn’t respond to emails and telephone messages seeking comment on the company’s operations and workers.

Citgo has all-American origins, being founded in Oklahoma in 1910. Today, there are roughly 5,300 Citgo-branded gas stations and an iconic sign bearing the triangular logo at Boston’s Fenway Park, home of baseball’s Red Sox. Few Americans know the company is owned by a socialist autocracy.

PDVSA gained control in 1990 and moved the 800-person headquarters to Houston from Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 2004. Neither company issues financial reports, but from 1998 to 2013 Citgo paid $9.3 billion to PDVSA, according to a November report by the Grupo Orinoco energy research organization in Caracas.

Now, Maduro desperately needs its revenue. Hyperinflation has made the bolivar functionally worthless, and food and medicine are scarce. Maduro has even mortgaged the business for hard currency: Equity of a parent company is collateral for some PDVSA bonds and a lifeline loan from Russia’s Rosneft Oil Co PJSC.

U.S. companies had been PDVSA’s biggest customer, but sanctions now prevent them from paying the regime for oil, which the White House said would cut Venezuela’s exports by $11 billion over the next year. Instead, payments must go into escrow accounts earmarked for Guaido’s shadow administration. In Washington, a Republican lawmaker said Thursday that the Trump administration may block foreign entities from dealing with the company -- and is preparing for a possible bankruptcy by Citgo.

On Thursday, Maduro’s public prosecutor promised an investigation into Guaido’s slate of board members. This week, they met in Houston with attorneys and some current Citgo officials, according to a person familiar with the matter, and received a financial overview of actions against the company and a report on refineries. Opposition lawyers have been sent to Delaware, where Citgo is registered, seeking to amend the company’s articles of incorporation, the person said, asking not to be named because the talks are private.

Caracas Microcosm

The international tumult echoes in Citgo’s squat building on Eldridge Parkway in Houston’s so-called Energy Corridor.

“Imagine the work environment," said Rice University’s Francisco Monaldi, a Venezuelan-born expert on energy politics. “They have two sets of board members. They are terrified of investigations. There are people wanting to leave the country.”

Soon after the U.S. imposed sanctions Jan. 28, Citgo workers made a sweep for any literature bearing PDVSA’s name, said a worker at the Lake Charles, Louisiana, refinery. It was even erased from the template for Power Point slides, the person said. In the Houston headquarters, a portrait of revolutionary icon Simon Bolivar disappeared from the fifth-floor executive suite.

Everyday business stalled because customers and business partners weren’t sure whether they could work with Citgo despite its Delaware incorporation. American employees hurried to inform clients that the U.S. Justice Department had explicitly authorized it to do business.

The number of Venezuelans in Houston working side by side with Americans has grown since 2004, but the relationship has been cool, according to a U.S. executive who retired last year.

Socialist Realism

The decor leaves no doubt about who has been in charge. Walls are lined with photos of Caracas and Venezuela. Pictures of Maduro and predecessor Hugo Chavez adorn the president’s office. Venezuelan and U.S. workers eat together -- usually at different tables -- in a cafeteria that always offers at least one Venezuelan entree.

For years, the company put its U.S. face forward to customers while regime loyalists filled the executive suite, said the retired official. The relationship was tricky, but Chavez largely left it alone. Things soured after Maduro assumed power in 2013. The president filled board and management slots with people who had political or family connections but little background in energy.

“The inner workings and policies began revolving around Venezuela and what Venezuela needed,’’ the former official said. “You started to see key positions held by people with no experience.’’

Fateful Summons

Talent retired or found other work. Not all departures were voluntary. In late 2017, Nelson Martinez, then head of PDVSA and a former Citgo president, summoned executives from Houston to Caracas for a budget meeting. Six were imprisoned, as Martinez himself was days later. He died in custody in December. Fourteen months later, the prisoners have yet to have a court hearing and are held in inhumane conditions, according to their families. Within days of the arrests, a cousin of Chavez was named Citgo’s new president.

Charles Alexander, a former project manager at the Louisiana refinery, said he was so outraged that he retired early last year. He said he knew two of the jailed men well.

“These are good men,” Alexander said “They’ve been falsely accused.”

The Houston headquarters has long been split between Venezuelan and American Citgo executives and representatives of the state-owned parent company, which another former top executive said was corrupt and “insatiably inept.’’

Thrown Out

PDVSA Services BV, a procurement and logistics subsidiary, set up shop inside the building. About 40 people worked for the company on the fifth floor. Most lost their jobs and visas last week.

The former executive said many Venezuelans at the headquarters support Guaido. The 35-year-old head of the National Assembly said last month that Maduro stole his re-election and that the constitution makes him the rightful leader. “There is a split inside the building,’’ the former executive said.

Still, hostility to Citgo’s Venezuelans for a presumed allegiance to Maduro has spilled into the community, said Joel Euaz, who was manning the counter of Tuttopane Bakery near Citgo’s headquarters. Although a neighboring Venezuelan restaurant put up a sign saying “Chavistas” loyal to the regime weren’t welcome, Euaz said he welcomes everyone. Television images of an anti-Maduro demonstration in Caracas played behind him.

Euaz said he doesn’t know whether Citgo employees are eating his arepas and meat-laden lunch plates. Workers don’t wear their badges in Venezuelan restaurants anymore, he said.

Many Citgo workers, American and Venezuelan alike, hope the chaos proves to be a deliverance and allows a competent company to disentangle itself from vicious politics.

“We may just get emancipated," the current executive said. “There’s a hope for the future."

--With assistance from Lucia Kassai, Fabiola Zerpa and Brian Welcher.

To contact the reporters on this story: David Wethe in Houston at dwethe@bloomberg.net;Margaret Newkirk in Atlanta at mnewkirk@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Casey at scasey4@bloomberg.net, ;David Gillen at dgillen3@bloomberg.net, Stephen Merelman, Anne Reifenberg

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.