At Home in East Hampton With Banker-Philosopher Peter Solomon

At Home in East Hampton With Banker-Philosopher Peter Solomon

(Bloomberg) -- It’s a late Monday morning in East Hampton, and investment banker Peter J. Solomon just spent an hour and a half putting back together a deal that fell apart the previous night.

It used to be that he wouldn’t dare do a conference call from the Hamptons on a Monday.

“People wouldn’t take you seriously," Solomon says. "Now, it’s what they think is going to happen.”

Solomon, who turned 80 last month, also isn’t expected to be toiling long hours in PJ Solomon, the investment bank he founded in 1989.

“If you’re my age, and you’re in the office, they sort of say to you, ‘Why are you in the office?’ I say, ‘Why am I not?’ It’s a very funny reversal.”

In his seventh decade on Wall Street, now as chairman of his firm, Solomon is at a rare juncture: He has plenty of energy and zest for dealmaking, yet he has deliberately stepped back from the firm. In 2016, he and his partners sold 51 percent to Natixis, and Marc Cooper became CEO.

Cooper is doubling headcount and Solomon is doubling down on his passions.

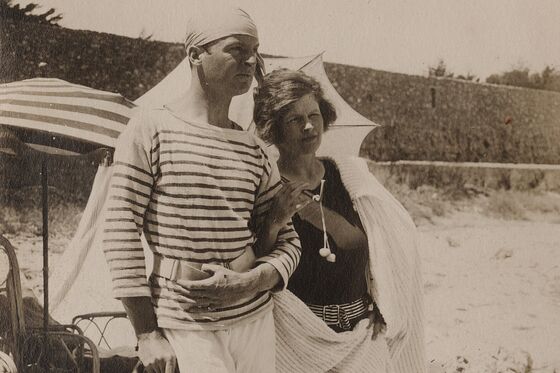

One of them is his house overlooking Hook Pond and the Maidstone Club golf course, which has an illustrious pedigree. Gerald and Sara Murphy, muses of F. Scott Fitzgerald and friends of Picasso, made it their home in the 1930s on land owned by her family, the Wiborgs.

Murphy, a painter who later ran his family’s business, Mark Cross, called the house Swan Cove. A swan carved of wood hangs on a pool-side portico and the honey from Solomon’s hives (225 pounds this year) gets distributed to friends in glass jars affixed with “Swan Cove” labels.

Solomon’s wife, Susan, is responsible for the inside of the house, while the outside is his domain. He spent a summer hacking weeds in the front yard to make way for a formal garden designed by Deborah Nevins.

“This is the Garden of the Finzi-Continis,” Solomon says. “We always have something in bloom.”

The wild area is in the back, a barrier between the lawn and the pond that Solomon himself planted to keep fertilizer and cut grass from going into the water.

"It’s the battle of evolution," he says, running his hands through stems of goldenrod and milkweed. "I don’t weed it or cut it. I see which plants can fight better than others."

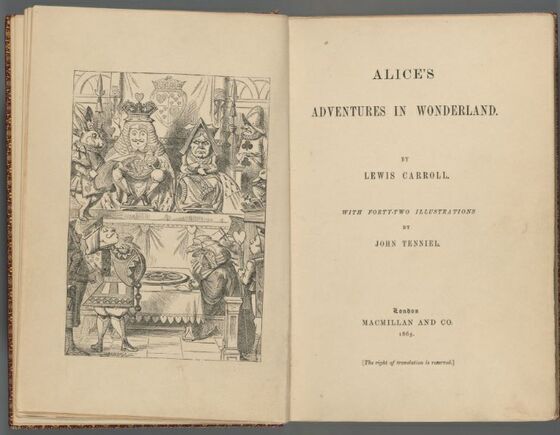

The hibiscus have grown tremendously in the past few months. “I’m a book collector -- Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll is the center of my collection -- and these remind me absolutely of Lewis Carroll flowers. Look at them!"

In addition to collecting books, Solomon has been writing one that shows off his range as a banker, philosopher, humorist and humanist. He calls it "Wasting Time Constructively: A Guide to a Balanced Life," and he plans to publish it on Lulu.

"It’s all stories," Solomon says.

The Wall Street stories start in the summer of 1958, calculating price-to-earnings ratios on hand-cranked machines in the statistics department of Merrill Lynch. He became a partner at Lehman Brothers in eight years, where one of his hires was Steve Schwarzman, who was always impressed that Solomon ran his own numbers.

In 1978, Solomon took a break from Wall Street to work in government. He was deputy mayor for economic policy and development under Mayor Ed Koch, and then counselor to the Treasury Department during President Jimmy Carter’s last year in office. After Carter lost the 1980 election, Solomon circled back to Lehman. Navigating the sale to Shearson, he rode the wild ’80s with its junk bonds and retail mergers, and became vice chairman heading investment banking and M&A.

When he left to form his own boutique advisory, it was one of the first. He represented Lands’ End in its sale to Sears and restaurant-survey firm Zagat in its acquisition by Google. His signature is a personal touch, and an emphasis on working with clients long-term, not just on specific transactions.

“Deals are done physically,” Solomon says. “Your intellect is interesting but it’s your energy that’s decisive. The numbers are the easiest thing. It’s the ability to talk to somebody, relate to them -- the client or the opposition.”

Personality and action drive deals through.

“A client of mine today said ‘I’m going to email someone.’ I said, ‘Like hell you are.’ You email them, they’ll kick that email to somebody else. You pick up the phone and you call them. And if they don’t want to speak to you, let them say ‘sorry.’ But you call them, say ‘I want to talk to you.”’

Having more time to impart lessons like this is one of the reasons he supported the Natixis investment. It also gives him the means to pursue some grander philanthropic projects.

“I wanted to have eight-figure charitable money instead of seven-figure,” Solomon says over a lunch of chicken salad and turmeric iced tea, with bread and his honey on the side. “There were things I wanted to do. And I’m doing them.”

One gift will build an insectarium with his name on it at the American Museum of Natural History -- “because it’s fun.” Another will underwrite the renovation of Houghton Library at Harvard, where his collection of children’s books and ephemera will go.

“I said, ‘I’ll only give you my collection if you will renovate Houghton Library and open it up. You don’t need my name on it, you’ll do something else for me."

A beekeeper for 40 years, Solomon used to suit up with his kids. Now his 12 grandchildren join him. He likes to sit and watch the bees, so there’s a chair next to each hive.

“This is what crazy bee people do,” he says. “You sit here like this and you just look at them. You can see them delivering pollen. As they come in they have orange on their wings, or yellow. Not to terrify you, but there are probably 40,000 bees in there, and another 30,000 next to them. When I ran for overseer of Harvard, I wrote a thing that said, ‘There’s nothing like 40,000 angry bees to focus your attention.’"

Solomon attributes his own attention to detail to his growing up in nature, and not to his father’s career in the retail industry, rising from the basement to the chairman’s office at Abraham & Straus. Dad gave him his “most pressured job ever” -- a summer on the receiving dock at the store in Hempstead -- as well as a calm retreat from their daily city life in Manhattan, a house on a golf course in Glen Cove, Long Island.

“I’d walk for two or three hours looking for balls and looking for bugs,” he recalls. “I’d be alone. And it was very influential on me."

Another formative moment was ending high school as the only person in his class who didn’t get into college.

"I was more upset than I let on," Solomon says. "You never want to be in that position again, with no options."

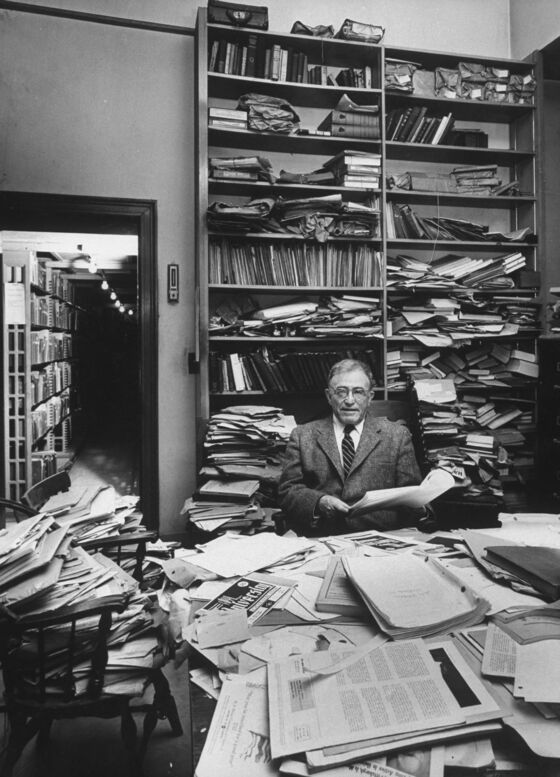

He wound up at Harvard after the university said he could enroll if he found his own room off campus. With help from family in Boston (who’d founded Stop & Shop), he moved into a house on Francis Avenue where economist John Kenneth Galbraith was a neighbor and Harry Austryn Wolfson, a reclusive scholar of comparative religion and philosophy, was his housemate.

"He had a key to Widener Library," Solomon says.

Their friendship was an unlikely one -- Wolfson was 51 years older -- but when Solomon was offered a place in the dorms at the end of the first semester, he turned it down. Instead he took Wolfson on the town -- on a drive to Wellesley to pick up a date. Solomon says he got help on a paper just once.

“I could not understand the Divine Comedy, and Wolfson understood everything about the Divine Comedy,” Solomon says. “In fact, I think he knew Dante. So I write this paper, and Wolfson said it would not do, here’s what you should write. And I get a C minus. Wolfson was hysterical, he couldn’t stop laughing.”

Three Buckets

Solomon generally sorts his philanthropy into three buckets -- tithing, supporting centers of excellence and backing entrepreneurs. His board service ranges from the Manhattan Theater Club to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. He founded Harvard’s Friends of the Center for Jewish Studies.

In his early 30s, he became the youngest board member by about 20 years of Mount Sinai Hospital -- tapped by Gus Levy, after an early-morning phone call summoning him to the trading floor of Goldman Sachs. He also persuaded a Young Lords gang leader not to burn down the Hudson Guild Neighborhood House.

“I said, ‘Let me tell you what happens: You go burn down the Hudson Guild, I get on the subway and go home. Now you are dealing with all the people who have their childcare at the Guild. Me, I will be uptown. You, you will be toast.”’

The gang leader followed Solomon’s advice, and started his own effort to help the neighborhood.

In East Hampton, Solomon is working on cleaning up Town Pond and Hook Pond. His prior government service comes in handy. "I understand the limits of government, how slowly they work, how you have to build consensus."

He has a new pleasure craft, a $1,400 kayak for bass fishing, a birthday present from his wife. Solomon also spends time collecting stray golf balls from the Maidstone course, to hit wedges in his backyard.

“I’m tired of playing golf, but I love hitting balls,” he says. “I’ve never broken a window but my 8-year-old grandson Jake has come close.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Amanda Gordon in New York at agordon01@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Pierre Paulden at ppaulden@bloomberg.net, Peter Eichenbaum, Steven Crabill

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.