Europe Is Ground Zero for Global Credit Fears

Europe Is Ground Zero for Global Credit Fears

(Bloomberg) -- Profit warnings here, accounting questions there, a missed coupon or two -- and suddenly something smells rotten in the state of the market.

CMC Ravenna, DIA, Douglas, Boparan: Just some of the hitherto obscure firms that have ensnared European credit investors in recent weeks. As losses add up and outflows persist, those fearing the end of the business cycle are no longer dismissing the bad news as isolated, idiosyncratic risks. Instead they see the start of a systemic shift.

“We are in the later stages of this cycle and we expect defaults will rise,” said Jeff Mueller, a London-based portfolio manager at Eaton Vance Management, which oversees $460 billion. “After the era of easy money and the associated lack of differentiation in credit risk, there should now be more of a focus from investors on picking the good over the bad.”

Mueller is voicing concern as Scott Minerd said the selloff in General Electric Co. bonds forebodes bigger woes: “The slide and collapse in investment grade credit has begun," the Guggenheim Partners chairman of investments and global chief investment officer tweeted.

Sure, the U.S. expansion looks longer in the tooth than Europe, with the investment-grade market held ransom to rising interest rates. But his warning resonates across the Atlantic, where companies are carrying bigger debt loads, like their U.S. counterparts, while investors get more selective as waning easy-money policies expose fragile balance sheets.

For now at least, default rates in the U.S. and Europe are low, keeping the lid on wider concerns about corporate health and high leverage multiples. But the threat is rising that these nagging doubts will exact a heavy toll on indebted companies at the worst time.

Many investors aren’t waiting. At the slightest whiff of bad news, they’re pushing the exit button to avoid potential credit landmines.

Take C.M.C di Ravenna Societa Cooperativa. The Italian builder’s announcement it won’t pay the coupons on its 2023 bonds on time due to “cash flow tension” came as little surprise to investors who’d pushed up yields on signs it was struggling under its debt load. They’ve punished Spain’s Aldesa SA alongside it, with the face value of its debt plummeting by more than a third within just a few months.

“Selling is leading to more selling so we need to pick our battles right now amid so much dispersion and fear,” said Olivier Monnoyeur, a high-yield portfolio manager at BNP Paribas Asset Management, which oversees 560 billion euros ($630 billion).

Holders of 2.1 billion euros of debt in German retailer Douglas took the unusual step of trying to limit losses by opting to freeze trading on the bonds in exchange for private company information, in the hope of staying ahead of retail risk and profit warnings.

Another recent target is Spanish supermarket chain Distribuidora Internacional de Alimentacion SA after the company surprised by slashing its earnings forecast and cutting its dividend.

So long as banks that lend to speculative-grade companies keep lines open, Mueller says systemic risk can be contained.

“The transfer mechanism from idiosyncratic to systemic risk is always difficult to predict,” he said. "In order for banks to get jittery I think we’ll need to see either a rise in actual defaults and the threat of companies going to the wall.”

Still, the multiplying red flags from retailers and builders raise the question, after a solid two years of eurozone growth, how will they cope in a downturn, without the backstop bid from the European Central Bank?

Benign default rates mask a higher proportion of vulnerable leveraged companies, according to Moody’s Investors Service, which warned this week of a global economic slowdown and rising funding costs.

"For some credits, we don’t see the path to deleveraging in the time they have left to maturity," said Sandra Veseli, a managing director at Moody’s.

Even as the rate of nonpayment for global speculative-grade firms slipped to a three-year low of 2.6 percent at the end of October by Moody’s estimates, trading tells a different story.

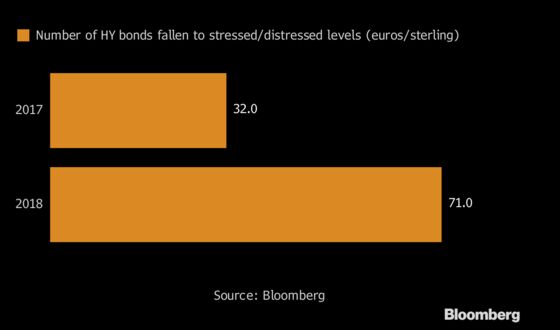

Since the start of the year to November, the number of stressed bonds (with a price of less than 90) and those in distress (a price of less than 60) has risen to 71 from 32, according to Bloomberg data.

"When will it all go wrong?” said Uli Gerhard, a senior portfolio manager at Insight Investment Management Ltd., which manages $791 billion of assets. “We have reached a point in the market where bottom up credit analysis is vital as the carry game facilitated by the ECB is coming to an end."

--With assistance from Ruth McGavin and Charles Daly.

To contact the reporter on this story: Laura Benitez in London at lbenitez1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sarah Husband at shusband@bloomberg.net, Cecile Gutscher, Sid Verma

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.