Argentina's Hot Summer of Packed Subways, More Theft And Floods

Argentina’s Summer of Discontent

(Bloomberg) -- Passengers quickly piled up on the subway platform on another hot summer day in Buenos Aires, and Micaela Goncalves was fed up with crowds that were larger than usual.

“There’s more people because the economy is pretty bad, inflation is high and people can’t go on vacation,” said Goncalves, a 24-year-old administrative assistant waiting for a delayed train without air conditioning to pull in.

Argentina’s capital typically witnesses a mass exodus when South American summer starts in late December. But with the economy in recession, a currency that lost half of its value since May, and salaries that can’t keep up with inflation, many have scrapped travel plans. At home, they found rising crime rates, an unusually heavy rainy season with occasional flooding, and an overall decline in their quality of life.

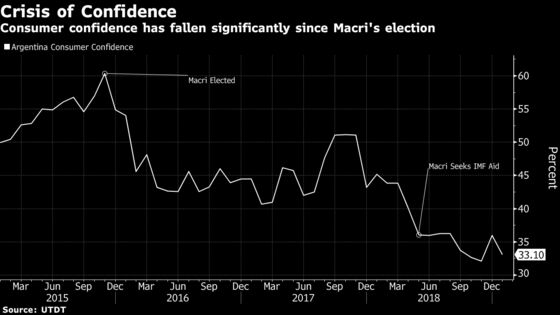

Streets aren’t filled with protesters, but disenchantment with President Mauricio Macri’s market-friendly policies is rising as he prepares to face former President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, his likely opponent in the October presidential election. For investors, Macri represents an antithesis to Kirchner’s populist policies that drove the country into an economic crisis. But, for most Argentines, his reforms have yet to translate into better living standards.

“The truth is that Macri’s term in office has been horrible,” Goncalves said. “Look at public transportation -- prices are rising all the time and it’s always the same.”

In Buenos Aires’ subway, the number of passengers as well as complaints about the system hit record highs last year. Ridership reached 338 million, up by 20 million from 2017. In the first nine months of 2018, complaints were already over 11,000, up 25 percent from the same period a year ago, according to city figures and Subte.Data, a non-profit research firm in Buenos Aires.

In order to reduce the large budget deficits that triggered a currency crisis last May, Macri had to speed up spending cuts. His austerity measures include removing subsidies that for years kept transportation and utilities prices in check.

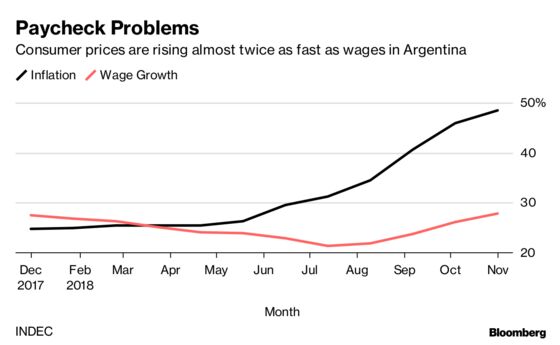

For example, the subway fare will be 21 pesos by April, up from 7.50 pesos a year ago. Salaries didn’t rise nearly enough to make up for inflation and subsidy cuts. Consumer prices jumped 49 percent in November from a year earlier while wages only grew 28 percent. And, with the central bank’s key interest rate at 55 percent, virtually no consumers or businesses have access to credit.

Nothing Is Selling

Business owners are bearing the brunt of the recession too. Sebastian Rossin estimates sales at his hardware store in downtown Buenos Aires dropped 30 percent last year while electricity, rent and his daughter’s high school tuition all went up. He had to lay off one of his two employees. He’s cutting back on meals out with his family.

“This recession is the worst -- you don’t sell anything and inflation is high,” said Rossin, 42. “Expenses are much higher, electricity is more expensive -- wages aren’t rising like all these things, so that’s the problem.”

With such a decline in purchasing power, poverty started rising again in the country -- and so did the number of robbery and thefts in Buenos Aires, according to an annual crime report. Out of Argentina’s population of 45 million, 12 million now live with less than $358 a month -- below the poverty line.

The weather isn’t helping either. After a historic drought crushed much of the country’s farmlands last year, recent heavy rains in four Argentine provinces have forced 6,000 people to evacuate, and the government to declare a state of emergency.

Those lucky enough to escape the gloom comprise a thinning slice of the population. The number of Argentines vacationing in Uruguay, for example, fell 36 percent from Dec. 24 to Jan. 22 compared to a year ago, according to Argentine government data.

Goncalves isn’t among them. Studying to be an architect, she makes 22,000 pesos a month ($587) at her assistant job. That’s 38 percent more than when she started in 2015, but the peso is down 77 percent over that period.

"I’m not going on vacation for now," she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Patrick Gillespie in Buenos Aires at pgillespie29@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Vivianne Rodrigues at vrodrigues3@bloomberg.net, Walter Brandimarte, Matthew Malinowski

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.